“They were cleaning out the space and one of our facilities folks — Mike Ray is his name — was looking up on one of the shelves, and tucked away in the top of this shelf, in the back corner of the bowels of this building, was this rolled up piece of canvas,” says Lisa Kinzel, director of research development at Mines. “And so he brought it up to me, and he unrolled it on my conference table, and we just stared at it.”

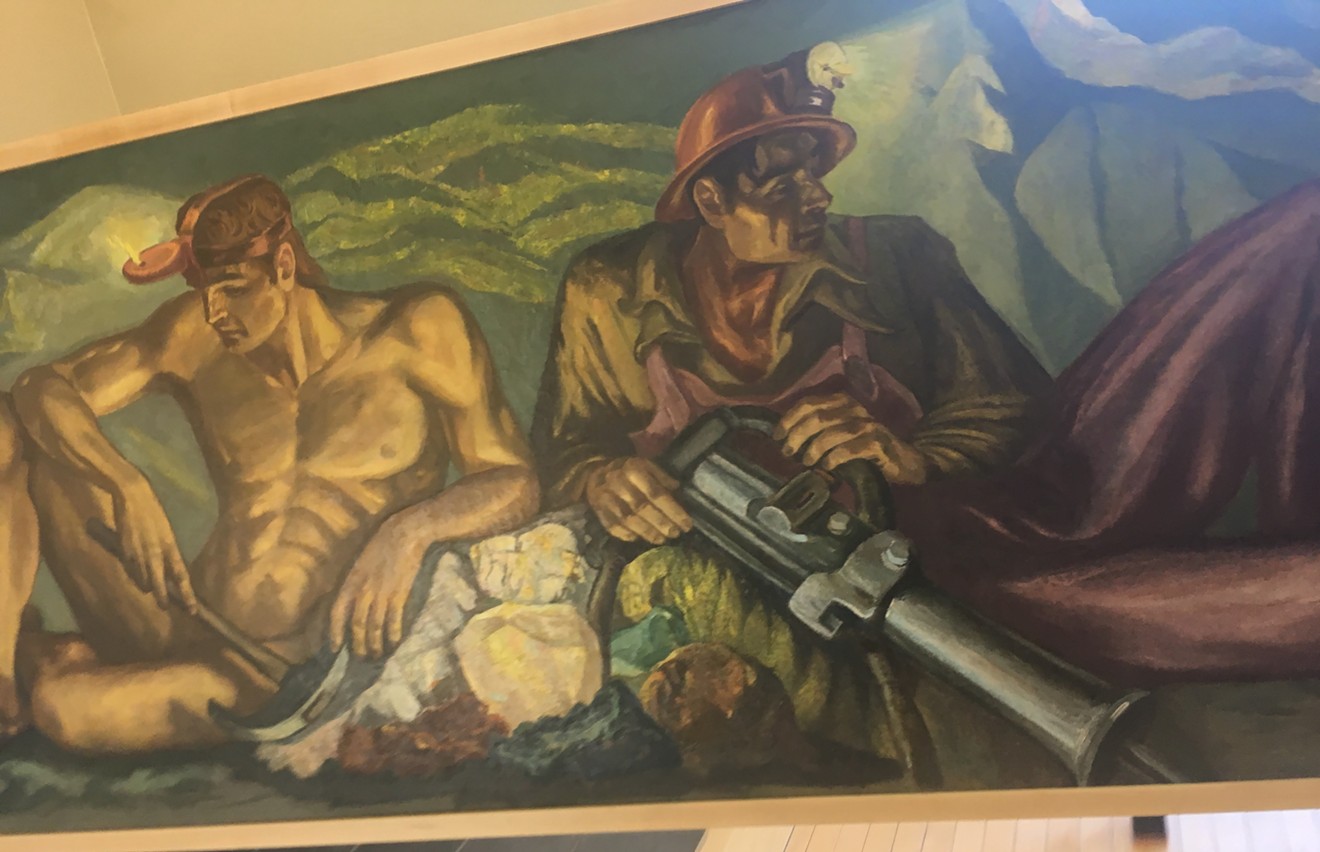

Close-up of paint damage on an Irwin Hoffman painting rediscovered at the Colorado School of Mines.

Lisa Kinzel

The six known seven-foot panels displayed in the Geology Museum begin with the discovery of flint and move through the major ages of metallurgy, including the Iron Age and the Bronze Age.

The sixth panel, which has long been seen as an ode to the world made possible by mining, includes both pros and cons of technological development. Among an ocean liner, a train and a radio, Hoffman also painted "an anti-aircraft battery manned by a crew in gas masks," wrote Theresa Cederholm in an account of the artist's life she wrote for the Boston Public Library. "The irony of this tribute to technology implies that civilization has reached the crossroads. Will the process of development and construction outstrip the forces of destruction?"

Because the paint on the newly discovered artwork was cracked and flaking, Kinzel called in Cindy Lawrence, the art conservationist who had restored the other Hoffmans in 2014.

An Irwin Hoffman painting was discovered at the Colorado School of Mines, but it was in rough shape.

Lisa Kinzel

Lawrence considered "trying to preserve the piece as the artist intended" a fascinating process.

Trevor Byrne of Dry Creek Gold Leaf, the framer who designed a simple maple border for the painting, recalls, “We don’t often come across art that was found that no one really knew about."

Irwin Hoffman's sketch of his brothers Arnold and Robert, originally published in the book Free Gold.

Amanda Pampuro

In 1981, Hoffman recounted some of his experiences for the Boston Public Library. The text, Irwin Hoffman: An Artist’s Life, is one of few surviving resources describing his life.

Illustration of Johnny Dillon, by Irwin Hoffman for Free Gold, a book on Canadian mining written by his brother Arnold.

Amanda Pampuro

Illustration by Irwin Hoffman for Free Gold, a book on Canadian mining written by his brother Arnold.

Amanda Pampuro

Until his death in 1989, Hoffman worked tirelessly out of a studio in New York. Lawrence postulates that the seventh Hoffman painting may have been hung over the door at the World’s Fair exhibition hall, like a title, to tell people what lay ahead. Questions remain about how the painting became separated from the rest, or how long it was stored in Engineering Hall.

Although those questions may never be answered, Hoffman did leave behind remarks about his process and the work that went into it.

"I went down every morning for two months and sketched in preparation for the murals I did for the San Francisco World’s Fair in 1938," Hoffman said. "Words cannot explain the mysterious and unreal quality of the world underground. It is a mixture of the dramatic and the ominous; it is felt rather than visual."