The heartbeat of the New Orleans All-Star Jam-Balaya event on August 24 -- reviewed in detail here -- was George Porter, Jr., one of the great bassists in modern musical history. Westword recently conducted an extended chat with Porter in the context of his current band, Porter Batiste Stoltz -- but the conversation also reveals plenty about his association with the Meters, all of whom participated in the Jam-Balaya. The complete Q&A as it appeared in February appears below.

George Porter is the bassist for Porter Batiste Stoltz, a three-piece whose mammoth grooves have made the players favorites among jam-band aficionados – but he's also a whole lot more. As a founding member of the Meters, a classic New Orleans combo, he helped establish a Big Easy sound that’s definitely not easy to duplicate, or plenty of other groups would have done so by now.

In the following Q&A, which provided the fodder for a February 14 Westword profile, Porter shares a big and fascinating chunk of his story. He discusses how the Vietnam war prompted his move from guitar to bass; his in-the-pocket technique; the anecdote that inspired the Gov’t Mule song “3 String George”; the genesis of the original Meters (Porter, Art Neville, Joseph “Zigaboo” Modeliste and Leo Nocentelli) and the drummer they left behind; the hip-hop acts that did, and didn’t, pay for sampling the group; a few of the music greats the Meters backed; the commercial success that eluded them; an appearance on the first season of Saturday Night Live that proved to be the beginning of the end; reunions, legal maneuvering and the rise of Porter Batiste Stoltz; and Porter’s frustration with rebuilding efforts in New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.

Read on to learn more about Porter’s home base – and his home bass:

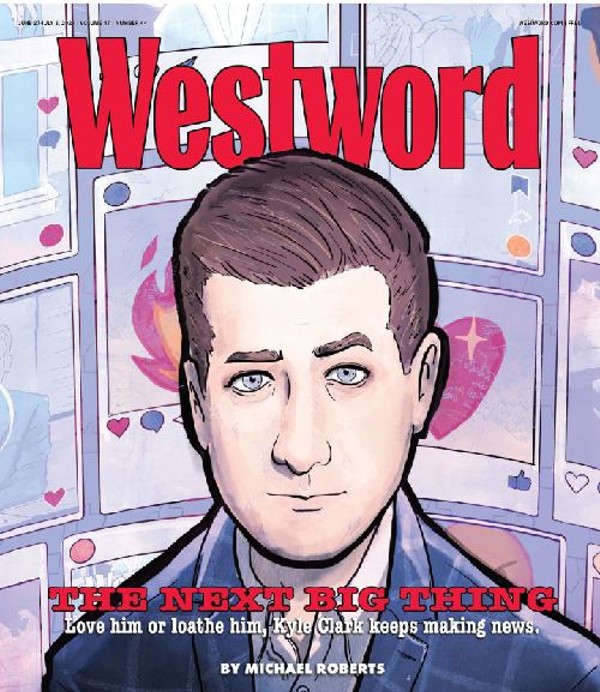

Westword (Michael Roberts): I understand that the bass wasn’t your first instrument. What did you start out playing?

George Porter: My first instrument was piano, and that was only two and a half, three months of lessons at the most, if they even lasted that long.

WW: How old were you then?

GP: I was seven going on eight. And those lessons were with Joseph Modeliste, the drummer for the Meters – they were with his older brother, Clinton. He was a violinist in the New Orleans Symphony, and he was giving both Zig and myself lessons. He couldn’t just give them to one. The competition was way too loud and boisterous, so Zig’s mom said, “I’ve just got to end it” – and we ended the piano lessons. But my mom gave me a guitar for my birthday/Christmas present at age eight, that next year.

WW: And how long did you play guitar before you made the switch to bass?

GP: I guess guitar was my instrument up until the Vietnam conflict. I want to say I was probably fourteen or fifteen years old. What had happened is, the young local electric bass players pretty much all got drafted. And I was born with a crooked spine, and that pretty much took me out of it. If it had been a war on paper, I would have been drafted – but because on paper it was called a civil action or something like that, I wasn’t a part of the draft. I was a 4F.

WW: So with that shortage of bass players, did you get recruited to switch instruments?

GP: Yeah, yeah. When I was playing guitar, I was playing and studying with a guy named Benjamin Francis, who was a bass player/guitar player – and he was a bass player first, guitar player second. And I was a guitar player/to-be bass player. I went from guitar to bass. That was after I got thrown out of my classes. I studied classical guitar with a teacher named Hamilton Brown, and I was kind of unruly and didn’t follow the programs very good. So I kind of got dismissed as a student, and at that point, I started studying with Poppy – hanging out with him more than studying. Just picking his brain, listen to what he played, saw how he did things, and then went home and practiced, practiced, practiced. And also, because of the classical training I’d been having for two, two and a half years, you learn how to play bass as well as rhythm and melodies. So I already had a finger on what bass players had to do as well. But with Poppy, we’d swap off playing guitar parts, where he’d be the bass player and then we’d switch off and I’d be the bass player.

WW: When you first started playing bass, did it seem really simple in comparison with guitar? Or did you know from the beginning that even though it may have seemed easier, there was a lot of complexity to it?

GP: I never saw the instrument as complex at all. I don’t know: I must’ve just felt that’s what I was supposed to be doing. I’ve never felt that there’s anything complex about either one of those instruments. I mean, there were things I knew I couldn’t do. The slap-bass thing that the young players have been using so much the past fifteen or twenty years, I never did develop that concept. I knew that wasn’t what I was supposed to be. And also, the speed-fingering concept of like Stanley Clarke – the real chops stuff. I never was that kind of player, either, and never wanted to be. I was more of a groove player, a pocket player.

WW: I understand that there’s a Gov’t Mule song named “3 String George” after you, because one of your early basses only had three strings. Is that true?

GP: Yeah, yeah. Warren [Haynes] called me up and asked me about it, asked if I’d have a problem with it. They didn’t want to do anything to insult me. And I said, “Nah, man, go ahead. Roll with it.”

WW: So what’s the story?

GP: Well, I bought a bass guitar from a guy named Richard Dixon. My very first bass guitar that I owned. I paid $50 for it. It was a Fender Jazz bass, and Richard had painted that thing bright red with house paint. But the bass had a bad nut up there on the tuning peg, and the thing came out. At the time, I didn’t know that I could go to the music store and buy another one. I really didn’t. So I played the bass with those three strings for a long time, until Art Neville said something. Art loves to tell that story. He’ll say, “You act like you’re big now, but I remember you when you only had three strings” (laughs). He does that on a nightly basis.

WW: I’m sure people were amazed with what a great sound you could get with three strings – but you’re such a funky player, you probably could have managed with just one…

GP: (Laughs.) Well, if it was a pocket that didn’t require a lot, yes I could!

WW: How did the Meters get started? Art was right in the middle of that, wasn’t he?

GP: Art was the organizer. He wanted to put together a band after being on the road with his brother Aaron supporting “Tell It Like It Is.” He came home and he wanted a band, so he went around the city looking for players, and he started off with – I think Leo Nocentelli might have been his first capture. And then I was the second player, and the drummer, he had a guy he wanted. I think he might have hired Sam Henry out of two musicians. Leo was playing guitar with Sam Henry, and Gary Brown was playing with Sam. It was a gig. Artie took the gig because Sam and them were playing at a joint called the Nightcap, and Art went in there and he hijacked Sam out of the gig for the most part – took two of his musicians and the gig. But we originally started playing at the Nightcap with another drummer named Glenn, and I can never remember what Glenn’s last name was. But Glenn had to go in for minor surgery, and it took him away for like two weeks or something like that. And during that period of time, Zigaboo was playing with one of Art’s neighbors, a guy by the name of Deacon Jones. And he got Zig to come in and play those gigs for us. It was like six gigs total over two weekends. And that second weekend, Glenn came in that Sunday night to let everyone know he was all right and he was coming back to work, and he heard Zig with the band. And I’m only guessing at this point, but I guess he thought, “There ain’t no way I’m getting this job back.”

WW: Was it like when a football player goes out with an injury and the backup turns out to be better than the starter?

GP: Absolutely. It was one of those kinds of things. At the end of the night, the club owner told us that Glenn had been there. But he never said anything, and the next day, he came in and got his drums and I never seen or heard of him again in my life. And he wasn’t no dog. Glenn was a good drummer. He was a really good drummer.

WW: He must have sensed that there was something special going on with you guys.

GP: Yeah, must have. And Gary Brown, he stayed with the band for a year and a half that we were up there and about six months after we moved to the French Quarter. And then Gary left, and that’s when we became a four-piece band.

WW: At what point did you realize that you guys had an incredible connection? Was it right away? Or was it only in retrospect?

GP: I started realizing the specialness about the band probably in the late ‘60s, when we were recording. But when we first went out on the road, we only had twelve songs of our own, and the rest of them were cover songs. But it was what we were doing to those cover songs that was special – and also what we were doing to the endings of the twelve songs that were on our first record. We were out playing gigs that were three-and-a-half hours, and all of the songs on our first record were only two-and-a-half minutes long. Every one of those songs turned into a jam, you know? And they went from there to another song. So what happened with that band was, in the late ‘60s, we were probably the very first jam band on the planet.

WW: I was going to ask about your popularity with jam-band fans. Sounds like it comes naturally.

GP: I think once those old Meters things started surfacing through the Internet, the kids, as well as some of the jam bands of the day – the Widespread Panics and other bands that came out around then and started playing our music – they’ve introduced us to another community of music buyers and listeners. And naturally, in the ‘80s and the ‘90s, when hip-hop took off, our music started getting sampled a lot. But the samplers, they never gave credit to where they were getting the music from.

WW: Especially in the beginning. You guys didn’t see any money out of that, did you?

GP: No, we didn’t see a nickel out of it. We were going after people like Queen Latifah and a bunch of other ones who all claimed they were broke and couldn’t pay us the money. In those days, all the records were licensed individually, so each record come out under its own agreement. And you go after that agreement and that band, and they’d say they were broke.

WW: Now that Queen Latifah’s a movie star, has she ever made good on that debt?

GP: No, she’s never made good. I think Heavy D, with “Gyrlz, They Love Me,” I think he came through with his. I don’t know all of them. I think there were 140-some-odd samples we know about, and about two-thirds of those samples finally paid off. The publishers of our songs went after them. We never really heard about how difficult the fights were. There was one song we were involved in, a lawsuit with Whitney Houston over one of her songs. We called ours “Hand Clapping Song.” I can’t remember what she called hers [“My Love Is Your Love”]. We ended up going to court with that one, and the judgment went against us. They said the song was public domain. It was an old church thing, and they said Leo actually took a piece of music that was out in the air, because they used it in church.

WW: In addition to recording as the Meters, you were on a bunch of sessions for other artists, too. What songs from that late ‘60s-early ‘70s period were you on that people might not know about?

GP: Oooh, you’re asking me to remember things (laughs). Well, there was Robert Palmer with Sneakin’ Sally Through the Alley, and a lot of write-ups give us credit for recording with Paul McCartney. But the band didn’t record with him as a band – just myself. McCartney was in New Orleans doing the Venus and Mars record, and he cut a Mardi Gras track that was only released during that Mardi Gras time. I don’t think the rest of the world even heard that song. But myself and Earl King and some other guys who were hanging around the studio during the time Paul did that session, we were on it. There was some tambourines and some cow bells and some hollering and screaming on that track. The Meters as a band never recorded with him. But I’ve done three records with Tori Amos, and also Johnny Adams and Snooks Eaglin and Robbie Robertson and David Byrne – I think that record was called Uh-Oh – and Patti LaBelle with the “Lady Marmalade” record. And tons and tons of Lee Dorsey. At least three albums of Lee Dorsey stuff, and at least one Allen Toussaint record, or maybe one and a half. He might have finished one of them in California. We were everywhere. We did a whole lot of sessions with Allen that kind of escape me right now…

WW: Your first recordings as the Meters sound very casual. Not something you planned…

GP: It wasn’t anything we planned. We were in a session, recording some Lee Dorsey tracks. Allen had left and we were in the Cos’s studio [owned by Cosimo Matassa] with Marshall Sehorn, Allen’s partner, just listening to some tracks. And I think he asked Cos, “Do you have some tape left?” or something like that. It was a two-track at the time, I believe. And Cos said, “Yeah, yeah.” So we went in and laid down four tracks. At the time, they didn’t have any names, but the first track we laid down was “Sophisticated Cissy” and then “Here Comes the Meter Man” and “Cissy Strut.” And then we made up a thing, I think we called it “Sehorn’s Farm,” but it was really “Turkey in the Straw.” Those were the first four tracks we made, and he named those songs – we didn’t even name them. And he put them out, and they went really well.

WW: Did that surprise you?

GP: Absolutely. We went back to our gig on Bourbon Street, and we were called back into the office and handed some paperwork and told, “Sign on the bottom line.” We were entering into a contract, and nobody had a clue what we were about to do. We put that signature on that contract, and we got a check for, I think, five grand apiece. And it took us twenty years to get out of.

WW: I was going to ask you about that. Wasn’t there some issue over the band’s name?

GP: Well, the band never owned the name. But no one owned it. We were always under the assumption that Marshall Sehorn owned the name “The Meters.” We were just led to believe that’s the way it was. He owned the band and he could do whatever it was he wanted to do. Whenever he wanted to chastise us, he would tell us, “I can fire you and hire somebody else to play the part.” But years and years later, when Art and I went and did research, we found out that the name had never been protected. So Art and myself copyrighted the name and put it under a corporation name, Funky Meters Inc.

WW: Why did you use “Funky Meters,” instead of just “The Meters”?

GP: Because the Meters had so much bad paper out there on it. We just didn’t want any of the old paper to start seizing on Funky Meters Inc. So we separated old business from new business by renaming the corporation. And then Funky Meters Inc. copyrighted “The Meters” and kept that separate.

WW: After you guys started recording together, you quickly got an incredible reputation with other musicians – but you didn’t become the sort of commercial success that a lot of people predicted for you. Was that frustrating? Or were you just happy to be playing music and making a living from it?

GP: I think it did frustrate some members of the band. That’s when the music started making a drastic change in direction, and the music started to be more commercial. Individual songwriters in the band their concept of what commercially valuable songs were and reaching for more of a commercial thing. Because we were playing gigs with bands that were opening acts for us, and by the middle ‘70s, those same bands had gold records out.

WW: Which ones?

GP: Earth, Wind & Fire. They didn’t open directly for us. It was a concert with them, then us, and Peggy Scott and Jo Jo Benson were the headliners. And two years later, three years later, those guys were getting gold records. And they had great writers – but better than the songwriting, they had somebody who was pushing them, working for them. We never had that. We never had management that wanted us to become superstars. And we had a record label that said, “You guys are too white to be black and too black to be white.” I never did understand that…

WW: They didn’t know how to market you?

GP: They had no clue had to market us. And we didn’t have a manager who had the right words and could go in there and say, “Go do this.”

WW: During the mid-‘70s, you guys opened a big tour for the Rolling Stones, just like Stevie Wonder did a few years earlier – and even thought it was a great period for Stevie Wonder, he didn’t always receive the warmest reception from the Stones’ fans. Did the fans get into your music right away?

GP: Not right away. It was a job that had to be won. We walked away from the U.S. Rolling Stones tour in very good shape, and the European tour even better. In Europe, we only had trouble in France. Every other gig we played in Europe, we were very well received, because we were better known. The Europeans have always embraced New Orleans music. The Meters were known there.

WW: We think of New Orleans’ culture as having such a strong French influence. It surprises me that your only problems were in France…

GP: Well, you know, I remember doing an interview with a French writer who kept sticking his finger in my eye about how France did this for New Orleans and how France did that. At the time, I was twenty-five, twenty-fix years old, and I didn’t see all that shit he was talking about. So I had a problem with him. The music we were playing had no French influence at all, and we were supposed to be doing an interview about the music we were playing, and instead, he kept saying, “The French did this” and “The French did that.” I didn’t find that. I remember going off on that guy. Like we should be so thankful to the French for giving us a culture. I just had a problem with that. At the time, I was probably a jerk, too, but I just didn’t see it. We were supposed to be talking about our music. I could have cared less about the culture.

WW: Did the Meters eventually break up because of what you mentioned earlier – some members wanted more commercial success?

GP: It had something to do with that, with the lack of business. Individually, Leo and myself were doing a lot more work without the guys. That was causing friction. And at the time, Art wanted to do things with his brothers. He wanted to bring his brothers into the band and have the Meters basically be the backup band for the Neville Brothers. Well, the other three of us didn’t want that, although Cyril [Neville] was in the band by then. But the band didn’t want to take on two more Neville brothers, which would have meant that the three of us – Zig, Leo and myself – would have definitely become sidemen in our band. We fought and fought against that. So Art, after recording the New Directions record, Art left the band. And during the project, the record label was really high on it. They were like, “This is going to be a good record,” and they spent a lot of extra money with the producer. They bought Allen Toussaint and Marshall Sehorn out of their contracts, because they noticed that the band wasn’t performing very well. And they got David Rubinson as the producer. They spent extra money and stuff. A couple of guys lost their job over that record.

WW: Because Art left?

GP: Because it all fell apart on their watch? Art quit the band, and they already had us scheduled on Saturday Night Live. They figured, if Art quit, we could put another keyboard player in the band, because we still had four of the five Meters, assuming that Cyril was staying in the band, too. And when the president of Warner Bros. came to talk to us, Cyril decided that he wasn’t going to do Saturday Night Live. So we ended up doing Saturday Night Live with just the three of us, with David Batiste, Sr. on keyboards. And the record label at that point decided to drop the record. It was going to be a good record, but the label pulled it. And that was pretty much the end of the Meters in the recording industry. I stayed in the band for probably another six months after that. We had hired another keyboard player and got Willie West to come in and do some front singing, and actually went into the studio to do some recording. That stuff never came out. I’m actually not sure where that stuff is. Who actually owns it, or who has it at this point.

WW: Did the band end when you quit?

GP: No, Leo and Zig continued on for another year or so, using the name with various bass players, before Zig left New Orleans and went to California. And Leo, shortly after Zig left, he split, too. At that point, I think that was the end of the band called the Meters. And then in around 1980, we got together, did a reunion, filmed it, recorded it and everything. There’s a master recording of that performance at the Saenger Theatre that is a masterful performance, musically as well as the way it’s recorded. But again, there’s a master tape somewhere out there, and no one knows where it’s at.

WW: Who owns it?

GP: Well, we know that the Meters own 51 percent of the project. We just don’t know where it’s at.

WW: There was a 1984 get-together, too, right?

GP: Yes, there was.

WW: And then in 1989, there was a full-scale reunion?

GP: Right.

WW: At what point did you begin playing with Russell and Brian?

GP: It must have been 1989 when Brian Stoltz came into the fold. Leo had left again. Leo, Art, myself and Russell Batiste started the band up again. Zig was asked if he wanted to come back in, and he declined. So we were calling the band the Meters, because there were three of us in the band. But we wanted to get legal and show income and stuff like that, pay taxes, and Leo didn’t want to do the corporation thing. He wanted to stay under the radar, so he declined. And that’s when Brian became an official member – and Russell was there already.

WW: People think of Russell and Brian as “the new guys,” but you’ve been playing with them for almost twenty years.

GP: Pretty close.

WW: What’s different for you playing with them in a trio versus playing with four or more players?

GP: The three-piece band definitely leans on being more powerful – more power funk. For most people, “power” means “louder,” and it probably is louder, but it isn’t that much louder than the Funky Meters. And we’re writing songs for a trio. We’re not writing songs with keyboard parts. The music is written for a trio, but we’re also vocal songs. Most of the songs are vocal. Out of each of the records we’ve done, there’s only been a few instrumental songs, and most of the rest have group vocals. That’s something we weren’t doing with the Funky Meters.

WW: How does your playing change? Do you feel you need to fill more space because there’s not a keyboard there?

GP: Yes and no. In the music we play, space is a very equal part of the music. It’s not what you play, it’s what you don’t play, that makes the syncopation work.

WW: You’re so closely associated with New Orleans. Are you leaving there at this point?

GP: I’m still in the area. Immediately after Hurricane Katrina – not even three months after – my wife got tired of running up and down the road with me and decided to buy us a home out in the country. So we bought a home out in a city called Darrow, Louisiana, which is 52 miles northwest of New Orleans. We’re right behind a town that’s well known for its jambalaya, Gonzales.

WW: Then you’ve gotten to see everything that’s happened in New Orleans over the past few years. Out here, we get some reports that the city’s really coming back and other reports that the situation is still really bad, and because the media’s not paying attention the way it had, there’s not as much pressure to get things done. What’s your take on where things stand right now?

GP: A little of all of that. There are parts of the city, very small pockets of the city, that are doing very, very well. And there’s a very large portion of the city – close to two-thirds of the city – where the neighborhoods are gone. I know Brad Pitt is working really hard in the Lower Ninth Ward trying to help repopulate that area, building homes and stuff down there. And they say the federal government is sending money our way. We just don’t see it. The state hired a corporation called Road Home to deal with that. It was supposed to be managing the money going to people, and right off the bat, the management took all this money as their salary before they started giving anybody anything. Right now, the whole world believes that Louisiana and the city of New Orleans is so corrupt that we can’t do nothing down here – and in order for the federal government to give us any money, they make us hire these people from outside, and then they hire a bunch of people, and then these people, who don’t know a damn thing about us, come down here, and they’re handling billions of dollars the feds gave to Louisiana. But they don’t know nothing about us. The wetlands are dying down there. We’re losing acres and acres of swamp and marshland. It’s sickening. Mississippi got almost the same amount of money we got, and they’re almost up and running totally.

WW: I can hear the frustration in your voice. It must have been very difficult to watch this process drag out…

GP: Absolutely. You look at the television and you listen to the radio, the national news, and the only thing they talk about down here is the crime. Man, the crime was here long before Hurricane Katrina. Ain’t nobody dying down here any different than they were dying before Hurricane Katrina. The same thugs who are killing each other down here now have been killing each other for the past two hundred years. There are no new thugs down here. It’s the same old thugs – the grandchildren of the original thugs. And they’re using it as an excuse not to do nothing. They say the mayor and the district attorney and this so-and-so and that so-and-so inherited a messed-up system. And then after the levees broke, [Mayor Ray] Nagin, it’s all supposed to be his fault. But he didn’t build those levees. The federal government built those levees, and the federal government managed and handled all the money that was put toward those levees. The city of New Orleans didn’t have anything to do with that. [He sighs.] That drives a hole in my head. I came out to the country to get away from it. Out here, I don’t have to look at that stuff all the time. I’ve got to run away from my home just to get piece of mind.

WW: Because your music is so associated with New Orleans, do you feel that wherever you play, you’re sending a message saying, “Don’t forget about the city. Don’t forget what’s happening down there”?

GP: Yeah, Art and myself are still out there playing, still out there bringing forth a happy face. We’re not out there preaching, and maybe we should be. But I just have a hard time going to a concert where people came to have fun, and all of a sudden I’m going to start preaching to them about how messed up shit is at home and we need more of your involvement. And most of the places we’ve gone, people have been involved. Everywhere we’ve gone, people have said they’ve done things. Their kids have raised pennies with their classmates and stuff and sent money to different charities inside the state. So I know that the everyday people, the people of the U.S., have stepped up. It’s just that the government hasn’t stepped up, and when they did step up, they put so many restrictions on what can and can’t be done, we had to hire knuckleheads from outside the state to come and manage our money and then they took big chunks for salaries. That could all have been put to better use in people’s lives.