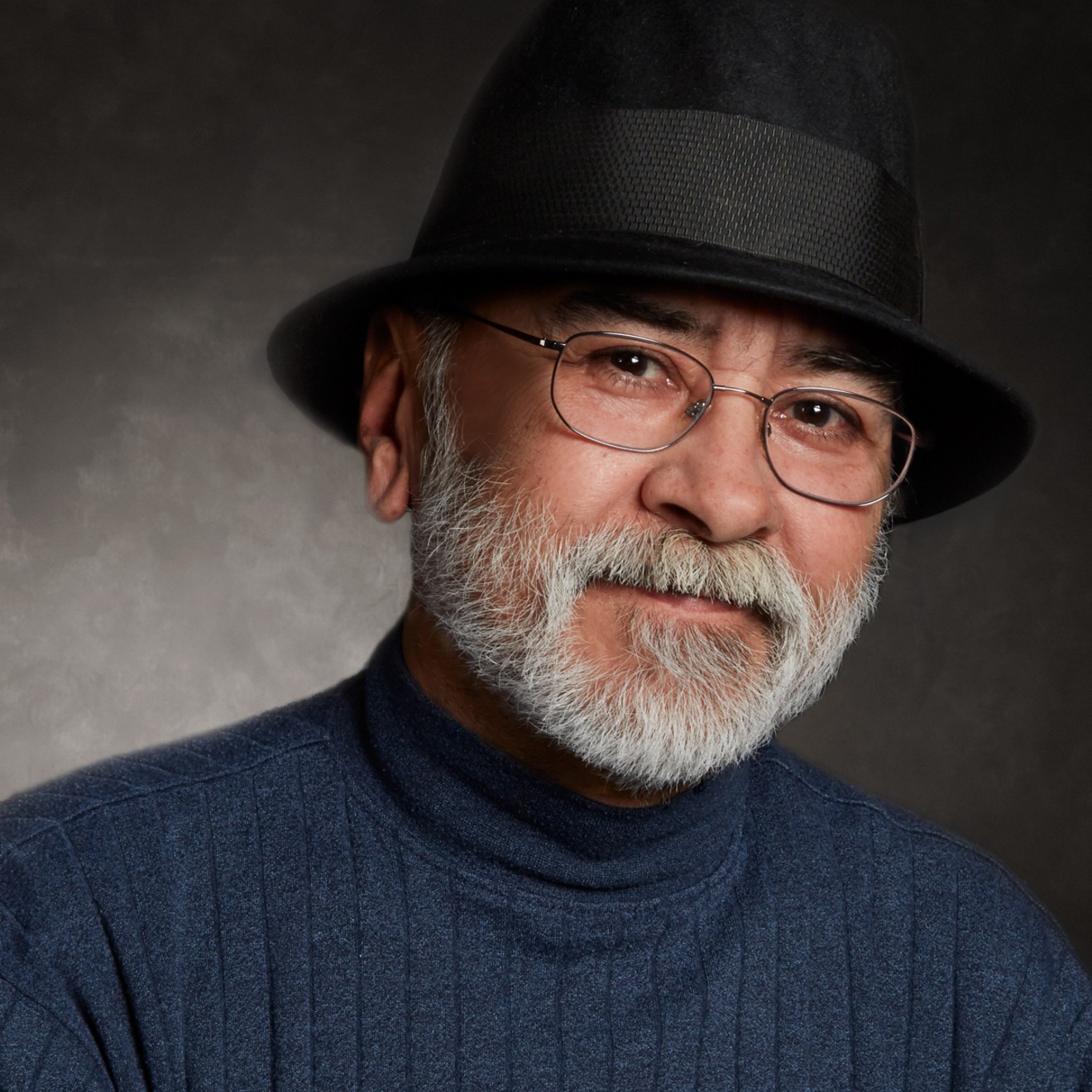

When Darold Vigil began hosting KUVO’s La Raza Rocks fifteen years ago under his radio name, Pocho Joe, part of his vision for the weekly show was to highlight what he calls the lost, forgotten and buried treasures of Chicano and Latin rock-based music.

“This is the kind of music that was not heard on commercial radio and never saw the light of day, in terms of the American public understanding that this is an American original art form,” he says. “But it was the kind of music Chicanos played at their parties, played in their basements, played at get-togethers, and the music that was historically significant to Chicanos throughout the southwest United States. It had never gotten its due.”

Vigil is being inducted into the Chicano Music Hall of Fame on Thursday, July 26, as part of Su Teatro’s 22nd annual Chicano Music Festival, which runs July 25 through July 29. Renowned accordionist Al Gallegos (still performing in his nineties), saxophonist and singer Larry Lobato Sr., and Pamela Liñan, who directs Mariachi Femenil Alma del Folklor, Denver’s first all-female mariachi group, are also being inducted.

While Gallegos and Liñan have been active in keeping Spanish-language music alive in the States, Vigil has been making sure the music gets on the airwaves while educating the public about the history of the artists he plays.

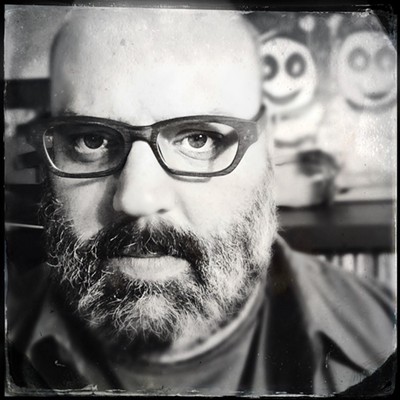

He began working on La Raza Rocks about a year after it started, and collaborated with Gabriel White from 2003 to 2011. From the beginning, Vigil says, he wanted to emphasize the historical significance of every song and artist.

“We know the story about Carlos Santana and the Santana band,” he says. “Many of us know the story about Ritchie Valens and what an impact he had on rock and roll, and he died at seventeen years old. His whole impact lasted nine months. Each and every one of these groups has a similar story, if not a greater story. Gabe agreed with my assertion that we should tell people about the artists, the music and the background. So as a focus, I came aboard and I made the background, the information, the history and the biographies about the artists as prominent as the music itself for La Raza Rocks.”

While there are hundreds of stories behind the songs he plays, he’s particularly fond of the tale of the band ? and the Mysterians, who had a hit with the 1966 song “96 Tears.”

“What many music critics pointed out was that the band and that song led to the rise of garage music and punk music,” Vigil says. “It’s kind of in-your-face, homemade, nitty-gritty good music, which led to the wave of punk and garage music.”

Vigil also says the Detroit-based band got airplay in part because no one knew at the time that its five members were all Mexican.

“They did get airplay on commercial radio, but they used the name ? & the Mysterians because this five-piece band were all Mexicans,” Vigil says. “They were all the sons of migrant farmworkers who landed in the Midwest and immigrated to Michigan to work in auto plants and get out of the fields. These were all Mexican kids singing ‘96 Tears,’ but in the late 1960s, nobody knew who they were. Nobody knew their real names, and nobody knew they were Mexicans — because if that fact came out, they would not get airplay.”

From the beginning, Vigil says, the emphasis of La Raza Rocks was to bring great music to the listening audience while having them understand how historically significant the music has been and is right now.

“American commercial radio had never played this music, frankly, because of racism,” Vigil notes. “Many of the artists had to change their names, like Ritchie Valens, to get airplay. His name is Ricardo Valenzuela, but he changed his name to Ritchie Valens so that the DJs in the 1950s would at least give his record a chance and put it on the airwaves.

“This is a chance for me, along with Gabe in those early years, to bring these things to the forefront, to let our listeners hear the stories behind the music and to know that although this music is the soundtrack to many of our lives, there was a deeper story than just the melody and the lyrics that we were listening to.”

On La Raza Rocks, which airs on KUVO from 1 to 2 p.m. on Sundays, Vigil plays artists from the 1940s, like Mexican-American guitarist and singer Eduardo “Lalo” Guerrero, and Don Tosti, a pioneer of the “Pachucho sound.” He’ll also play more current acts, like Ozomatli, Las Cafeteras and Chicano Batman, mixing in songs from all the decades in between.

“When we go back to the 1940s,” Vigil says, “it could be really a jazz-based post-bop swing type of music, to the 1950s, which is really serious fundamental rock and roll done by Chicanos and Mexicans. The 1960s was the wave of the bands that most people know about — El Chicano, Santana, Malo — bands that coincided with the Chicano civil-rights movement.” Vigil also spins Chicano punk bands from the ’70s and ’80s, as well as Chicano heavy-metal bands.

“The roots of Chicano and Latino music are woven through all the genres and all the styles,” Vigil says. “In the 1990s and 2000s, we have prominent bands that really go back a decade or two earlier but got their due in the ’90s and early 2000s, like Los Lobos and the Blazers, whose genre of music you really can’t put your thumb on because it’s so unique and they cover so many ranges of music, from Mexican rancheras and cumbias to reggae to soul music.”

Denver, Vigil notes, has long had a driving Chicano music scene, going back to the 1940s and 1950s; bands played in venues along Larimer Street when it was likened to skid row, decades before Coors Field was built and gentrification transformed much of it. Vigil says that in later years, there were a lot of Chicano rock bands who played parties, weddings and for their community, but many of them never recorded their music.

“Many Chicano bands, because of economics, could not record a record, but the biggest reason was that the record companies would not afford Chicanos and Latinos the ability or the opportunity to go into the recording studio and cut a record,” he explains. “So many of these bands of the thriving music scene that has been going in Denver for decades and decades was something that the Chicano and Mexican community knew about but the community at large was ignorant to — ignorant of the fact that these bands existed and the quality of music that they provided, whether it was jazz or Mexican music or rock and roll. It was just a world-class standard of music that they could have heard if they opened their hearts and ears to it.

“And I think that scene is continuing today with Chicano music,” Vigil says. “There are a number of Chicano and Mexican rock bands that have been emerging in the last twenty years in Denver that are really providing some good-quality music. I’m hoping that they get some national recognition, because Denver always has been a thriving music scene — but it’s been an underground music scene because of the ethnicity of the artists.”

Chicano Music Hall of Fame Induction

7 p.m. Thursday, July 26, Su Teatro Cultural and Performing Arts Center, 721 Santa Fe Drive, $6.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]