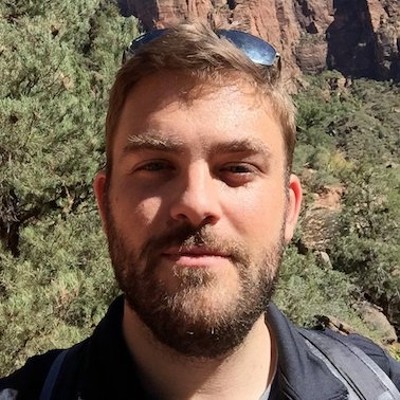

Ethan Lutz got his start in the oil and gas industry entirely by accident. The newspaper ad he answered in 2007 was for a paid training program for a commercial driver’s license, and it was only after he finished the training that he learned he’d been getting paid by an oil-field services company. He was given a choice: He could go to Rock Springs, Wyoming, and work for the company for at least two years — or repay the cost of the training. “I was like, ‘I guess I’m in the oil field now,’” he says. “I literally had to go home and Google ‘What is fracking?’”

After the recession hit and the natural gas market crashed, Lutz found work outside the industry. But in 2011, he was recruited by Denver-based startup Liberty Oilfield Services, where he’s been ever since, working his way up from a rookie “green hat” to an experienced crew leader. Today he manages three crews of about fifteen workers each, who are assigned to well sites where they’re responsible for the phase of modern oil and gas production known as hydraulic fracturing, or fracking — a process by which fluids are blasted at high pressures deep underground to loosen deposits for extraction.

“It’s good money, but it’s hard work, and it’s a lot of responsibility,” says Lutz. “We expect a lot from guys. Every company expects a lot from guys.” Frac crews typically work in rotations, with two weeks of fourteen-hour days followed by a week off. With no prior training, workers can expect to earn around $70,000 in their first year, with bonuses paid out for meeting safety goals.

“I know dozens of people that this job, jobs like this, gave them the ability to stop renting, purchase a home and start a family, myself included,” says Lutz, who lives in Arvada with his wife and two children. “I don’t know where I would be if I hadn’t gotten hired by my company.”

More than 20,000 Coloradans work in the oil fields of the northern Front Range and the Western Slope. They’re compensated well and receive good benefits in a country where that’s true of fewer and fewer jobs every year. These are the kind of jobs that careers are made of, the kind that communities have long been built upon.

And yet the overwhelming scientific consensus is that if the world hopes to avert disastrous levels of climate change, none of them can exist in twenty to thirty years.

“By 2050, we should be close to zero carbon,” says Lorne Stockman, a senior research analyst with Washington, D.C.-based climate advocacy group Oil Change International. “The science is very, very clear that this has to happen. There’s no alternative; there’s no technology that’s going to come and save the fossil-fuel industry. The only way forward is to wind down the industry, as difficult as that is.”

In the most comprehensive assessment of global climate science completed to date, a landmark report released last year by the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), scientists warned that the world must cut carbon emissions nearly in half over the next decade and achieve net-zero emissions by no later than mid-century. Achieving these targets will require “rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes to all aspects of society,” the report’s authors wrote, but failing to meet them could lead to global catastrophe.

And large-scale production and combustion of oil and gas is incompatible with a zero-emissions world.

Today, the two fuel sources together account for more than half of global energy-related carbon-dioxide emissions, and an even higher percentage in the U.S. and other developed countries where coal-fired power is in retreat. Any number of technological advances could, in the coming decades, make liquid and gas fuels — which account for more than 95 percent of the end uses of oil and gas — incrementally cleaner or more efficient. But none will change the fact that the combustion of hydrocarbon molecules releases carbon into the atmosphere.

Under Governor Jared Polis and a new Democratic legislature, Colorado has joined other states and countries around the world in pursuing ambitious decarbonization goals and a wide range of incentives for clean energy. While testifying before the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis in a field hearing in Boulder last month, Polis called climate change “an existential threat to our security, our health, our economy, our public lands and ecosystems, and our very way of life.”

But even as the governor and other state leaders tout Colorado’s plans for “bold climate action,” the state’s oil and gas industry is on an unprecedented hot streak, shattering production records and investing billions in its future. Between 1981 and 2009, Colorado oil production remained relatively steady, averaging a little under 30 million barrels annually. Last year, drillers produced nearly 180 million barrels of crude, a staggering fivefold increase in just the last decade, and production is expected to continue to rise for the foreseeable future, reaching nearly 250 million barrels by 2025.

Colorado Democrats talk openly of the end of coal, which is likely to be largely eliminated from the state’s energy mix within the next decade. But they dance around questions about the future of oil and gas — a much larger, more powerful industry that has long wielded great influence at the State Capitol. Supporters of aggressive climate action worry that by failing to confront the issue directly, policy makers are putting the state at risk for a disruptive, destabilizing energy transition that leaves workers and communities worse off.

“We are absolutely not doing enough to be prepared,” says Deborah McNamara, a campaign coordinator for climate advocacy group 350 Colorado. “We need to start connecting these dots now. We need a transition plan, and everybody needs to be working on this.”

At heart, activists want leaders to answer — or at least begin to ask — a harsh, critical question: After more than a century as a pillar of Colorado’s economy, how does the oil and gas industry end?

Oil was first produced from the Denver Basin on a ranch outside of Boulder in 1902 (left). A modern rig drills for oil and gas in Weld County, where there are more than 30,000 active and abandoned wells.

Boulder Historical Society / WildEarth Guardians

Tucked away in a seldom-visited corner of the Denver Federal Center in Lakewood, tens of millions of pounds of rock sit in a barrel-roofed, Cold War-era government warehouse, packed tightly into cardboard boxes and stored in row after row of heavily reinforced shelves. Established in 1974, the U.S. Geological Survey’s Core Research Center houses tens of thousands of rock cores, cylindrical sections of earth extracted from boreholes all over the West. Its repository is open to everyone, but the vast majority of its cores come from oil and gas wells, and most of its visitors are industry geologists who pore over its samples with special tools, looking for secrets in the rock.

“We provide open access to industry, federal agencies and anybody in the public who wants to come and look at samples,” says Christopher Skinner, an associate program coordinator with the USGS. “Whatever they do with them is their purview.”

Ninety million years ago, a narrow sea stretched from the Arctic to the Gulf of Mexico, splitting the North American continent in two. Shallow and warm, it teemed with life, from microscopic plankton and algae formations to giant prehistoric sharks and fifty-foot-long mosasaurs. Its western shore was an ever-shifting landscape of river deltas and low-lying floodplains formed by drainage from the still-growing Rocky Mountains. Over thousands of millennia, the sea receded and advanced and receded again across present-day Colorado, sinking layer after layer of sandstone and shale, rich with organic matter, into the Earth’s crust.

Buried there, subjected to extreme heat and pressure for tens of millions of years, this fossilized biomass was first compacted into a substance known as kerogen and then degraded into hydrocarbons like petroleum and natural gas. These vast fossil-fuel deposits slowly migrated through the earth and collected into underground reservoirs, trapped thousands of feet beneath the surface at the base of the Front Range, cradled by a concave layer of rock that geologists today call the Denver Basin.

The U.S. Geological Survey's Core Research Center stores rock samples from over 242 million feet of sub-surface drilling.

Chase Woodruff

It was work done by geologists at the Core Research Center and its massive rock repository that helped make this growth possible. “There was a well [in the Denver Basin] in the ’90s, and we had rock from that drilling process stored in our library,” Skinner says. “With the technology at the time, the well wasn’t conducive to completion. But they looked at the well in subsequent years, and now that the technology has changed, they were able to find additional resources.”

By bureaucratic happenstance, the Core Research Center and its steady stream of visiting petroleum geologists share a space in the Federal Center’s Building 810 with a highly specialized laboratory that’s home to some of the world’s clearest, most definitive evidence of the threat posed by fossil-fuel production. The National Science Foundation’s Ice Core Facility is a building within a building, a giant walk-in freezer that stores its contents — thousands of sections of ice extracted from deep beneath the surfaces of Antarctica and Greenland — at a crisp minus-26 degrees Fahrenheit.

The vast ice sheets that lie near the Earth’s poles have accumulated layer after layer of snowfall for hundreds of thousands of years, making them exquisitely preserved, extremely precise records of the planet’s climate history. There are dozens of ice cores housed in the NSF’s Lakewood facility; the most extensive, drilled near Antarctica’s Vostok research station in 1995, reached a depth of over 3,300 meters, or approximately 10,827 feet, capturing a series of climatological snapshots extending 400,000 years into the past.

Thanks to tiny air bubbles trapped in the Vostok ice core and others, scientists know that for most of the last half a million years — a time period encompassing the entire span of human history — the average level of carbon dioxide in the Earth’s atmosphere fluctuated between 180 and 300 parts per million (ppm). Shortly after the dawn of the fossil-fuel era in the late nineteenth century, however, those levels began to rise, passing the 300 ppm threshold in 1910, and in the past few decades they’ve passed alarming milestones at an accelerating pace: 350 ppm in 1988, 375 ppm in 2003, 400 ppm in 2015.

This year, with global emissions still on the rise, average CO2 concentrations have exceeded 411 ppm, their highest level in perhaps three million years. Along with other heat-trapping gases like methane, the carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere by human activity over the past two centuries has already caused the planet to warm by an average of about two degrees Fahrenheit, leading to destructive climate impacts all over the world. Here in Colorado, rising temperatures have deepened a decades-long drought, hurting farmers and ranchers, increasing wildfire risks and exacerbating bark-beetle infestations that have devastated more than one-fifth of the state's forestland.

Dan Gibbs, the director of Colorado’s Department of Natural Resources, has battled these climate-intensified wildfires for more than a decade as a volunteer firefighter. “It’s like the Fourth of July, in a bad way,” he says of the dried-out, beetle-infested trees that spark and explode as they go up in flames. Nineteen of the twenty largest wildfires in Colorado history have occurred since 2002.

It’s hard to concisely describe the chain reaction of catastrophic events that will unfold if atmospheric carbon-dioxide levels continue to rise in the coming decades. On their current trajectory, concentrations will hit 500 ppm sometime in the 2040s, causing global temperatures to rise by 5°F or more within many of our lifetimes. Entire regions of the world will become uninhabitable due to heat waves and drought. Crop yields will collapse, leading to famines and price shocks that harm public health, destabilize governments and ignite civil unrest. Rising sea levels will inundate a third of the world’s cities. Natural disasters like wildfires, floods and hurricanes will become more frequent and more destructive. Millions of people will die; hundreds of millions will become refugees; billions will be poorer, sicker and less safe.

Dan Gibbs has battled climate-intensified wildfires as a volunteer firefighter and now leads the Colorado Department of Natural Resources.

Colorado Department of Natural Resources

Does that include oil and gas production? After all, every well that’s drilled in Colorado — every one of the 40,000 active and inactive wells scattered across the Denver Basin — must go through a COGCC permitting process. Will the commission still be green-lighting new wells in 2040, when scientists say that oil and gas consumption should be nearing its end? In lieu of answering directly, Gibbs produces a chart showing the fluctuations in the price of a barrel of crude oil over the past few decades.

“I personally think this has more to do with the demand for oil and gas than anything else,” he says, tapping the chart. “That has more to do with whether or not they’re financially able to have a presence in Colorado.”

Few of the people who gathered in the Four Seasons Ballroom at the Colorado Convention Center in late August had ever driven a frac truck, fished a drill string or swung a sledge at a hammer union. Caterers fanned out across the room to serve lunch as attendees of the Colorado Oil and Gas Association’s annual Energy Summit directed their attention toward the stage, where COGA president Dan Haley welcomed his keynote guest, Governor Polis. Among the topics discussed in the 45-minute conversation that followed were climate change and the state’s efforts to address it.

“I think if you talk to folks in our industry, we believe that we are part of that solution as well,” Haley told the governor. “It’s frustrating for us at times, because I feel like people aren’t hearing that message or understanding the efforts our folks are going through, to really use that technology and innovation to clean the air and do the right thing by Coloradans.”

There are no active oil and gas wells within the City and County of Denver — only a few dozen old, abandoned drilling sites scattered around the city’s edges, most of them in and around Denver International Airport. But the industry feels ever-present in the city anyway, from the headquarters that line 17th Street and the small army of lobbyists who descend on the State Capitol every year to the election-season TV ads and corporate sponsorships at events all over town. (Amid the oil boom of the early 1980s, as much as half of all high-rise office space in downtown Denver was leased by energy companies; today, it’s around 15 percent.) This is the oil and gas business as many Denver residents know it: a white-collar world of CEOs and SVPs, compliance officers and energy law practices, market analysts and investment advisers, number-crunchers and PR pros.

As many of the attendees and panelists at the Energy Summit made clear, Denver’s reach in the energy world extends far beyond Colorado. Fossil-fuel giant BP owns few oil and gas assets in the state and none in the Denver Basin, but still chose Denver for its new Lower 48 headquarters, which opened last year, because of the city’s status as an “important energy hub of the future.” Among the amenities offered by BP’s brand-new, 160,000-square-foot Platte Street office are a two-story lounge called the Nest, where employees can relax in hanging daybeds and hammocks, and a cafeteria centered around a “Unity Table” carved from the 52-foot-long trunk of a lodgepole pine.

Before a crowd of powerful oil and gas executives at the Energy Summit’s keynote luncheon, Polis repeatedly demurred when pressed by Haley on the industry’s future in Colorado. Like Gibbs, he pointed to commodity prices and global market conditions as the ultimate driver of the future of energy, which he called an “inherently economic” question.

“I think what a lot of people want to hear — people want to feel like they’re valued, and their jobs are valued,” Haley told Polis during what was at times an awkward back-and-forth. “That they’re wanted in this state. For a long time, and especially this year, a lot of us have felt like we’re not.”

“Your jobs are valued, and you’re an important part of the diversity of our state,” Polis said. For the first time since he’d come on stage, the crowd applauded, then returned to eating lunch.

You wouldn’t know it from the tone of this ad-hoc group therapy session, but these are boom times for the oil and gas industry in Colorado and beyond. Beginning in the late 2000s, new fracking methods, along with other technological advances like horizontal drilling, unleashed what has been dubbed the “Shale Revolution,” leading to unprecedented growth in production all over the country. It took more than a century for the industry to produce the Denver Basin’s one-billionth barrel of oil, but Colorado operators have now nearly doubled that figure by producing close to another billion barrels in just the last decade. The same explosive growth has occurred in oil fields all across the country; last year the U.S. passed Saudi Arabia and Russia to become the world’s largest oil producer, a development that would have been unthinkable just ten years ago.

In Colorado, however, where much of the Denver Basin lies directly underneath the dense, fast-growing suburbs of the northern Front Range, the Shale Revolution has often looked more like a civil war. Clashes between oil and gas interests and communities opposed to fracking in their back yards have roiled state politics for years, leading to multiple failed ballot initiatives, high-stakes lawsuits and aborted compromises at the Capitol. In April, Democratic lawmakers at long last passed Senate Bill 181, a package of reforms that strengthened health and safety protections and granted local governments more control over drilling within their borders.

“You could almost market it as a locally driven oil and gas bill,” says Gibbs, who is overseeing the law’s implementation as director of the DNR. “It gives local communities the option, if they so wish, to help shape where they may want to see oil and gas in their community.”

The bill was fiercely opposed by trade groups like COGA and the Colorado Petroleum Council, who argued that operators, in response to existing regulation and community pressure, were already doing enough to control emissions and mitigate other environmental impacts. Lutz, who was hired by Liberty Oilfield Services just as the Shale Revolution was getting under way, says things have changed dramatically within the industry over the past ten years.

Ethan Lutz leads crews that perform hydraulic fracturing at oil and gas sites along the Front Range.

Caitlin Steuben Photography

A major point of emphasis for regulators and the industry over the past decade has been limiting leakage of methane, the primary component of natural gas and an especially powerful greenhouse gas. Atmospheric concentrations of methane have been rising for over a century, but they began to spike even further just as shale drilling became common in the late 2000s. Colorado became the first state to enact regulations requiring operators to detect and fix methane leaks in 2014, and it did so with support from several major operators; because methane leaks are essentially wasted natural gas, the industry has an economic incentive to minimize leakage.

“Oil and gas companies, they’re aggressive in pursuing technology that makes it safer and makes it less intrusive,” Lutz says. “People are passionate about making it better, making it safer, making it cleaner.”

It’s certainly true that by limiting “upstream” emissions — minimizing leaks on site, using electric power instead of gas generators — operators can reduce the industry’s direct carbon footprint. But no matter how climate-friendly its own operations may be, as long as the industry is still producing oil and gas in large quantities, they’ll be sending it downstream in the supply chain, where it will be burned in car engines, power plants, home heating systems and more, releasing carbon into the atmosphere and further warming the planet.

Despite the industry’s best efforts to pretend otherwise, that’s true even of natural gas, which has steadily evolved from the hydrocarbon family’s redheaded stepchild — historically, it was often simply vented in massive quantities as drillers sought oil alone — into its saving grace, relentlessly marketed as a cleaner-burning alternative to coal. Industry groups correctly point out that the transition from coal- to gas-fired power plants has been responsible for most of the progress in reducing emissions from the electricity sector over the last decade. But Stockman of Oil Change International says that with global emissions still on the rise and time running out to make drastic cuts, the days of natural gas as a viable “bridge fuel” are over.

“We’re beyond that point, where we can use gas as a transition fuel,” he says. “We’re over that ‘bridge,’ if you like. Any model that you look at that charts a path toward the Paris climate goals, gas has to go into decline.”

On stage at last month’s Energy Summit, during an hour-long panel titled “Responsiveness to Climate and Environment Through Technology and Investment,” panelists never got around to being responsive to this particular climate reality. Instead, Richard Jackson, president of “low carbon ventures” at Occidental Petroleum — which last month became Colorado’s largest oil and gas operator following its $55 billion acquisition of Anadarko — touted the potential of a suite of technologies known as carbon capture, utilization and storage, or CCUS for short.

“We’ve been a large consumer of CO2 for over four decades,” Jackson said, describing Occidental’s investment in a process known as enhanced oil recovery, through which carbon dioxide can be injected into otherwise depleted underground oil reservoirs, removing it from the atmosphere while allowing more oil to be extracted. “The challenge is how we take emissions and separate CO2 in a cost-effective way.”

Enhanced oil recovery and other CCUS technologies are quickly coming into focus as the industry’s last, best hope of maintaining any kind of long-term presence in world energy markets. But results on the ground have long cast doubt on their viability. Despite decades of research and development and billions invested by the fossil-fuel industry in CCUS, the two dozen or so projects currently operating around the world collectively capture about 30 million tons of carbon dioxide per year, enough to offset about 0.08 percent of annual global emissions. While the technology is likely to improve and play at least a small role in climate mitigation strategies, energy experts overwhelmingly view the transition to renewables and other clean-energy technologies as a more cost-effective way to reduce emissions.

“Carbon capture is a very expensive way to deal with climate change compared to some of the other options that we have,” says Stockman. “It’s just going to be prohibitively expensive and push a lot of costs onto electricity customers. It’s clear that actual clean technology is going to be far more affordable than trying to capture carbon and store it.”

Polis ran on a promise of putting Colorado on a path to achieve a 100 percent renewable electric grid by 2040, and his top energy official has spoken of electrifying nearly all light-duty vehicles in the state by the same date. Lawmakers have passed a wide range of incentives for utilities and electric-vehicle buyers to help meet those targets, along with a bill committing the state to a series of economy-wide decarbonization goals, including a 50 percent overall emissions cut by 2030 and a 90 percent cut by 2050.

Proponents of Colorado’s market-based, consumer-focused approach to climate policy are bullish on its potential to decarbonize the state’s economy over the next several decades. Today, it’s cheaper than ever for utilities to build new wind and solar generating capacity, and Colorado’s largest electricity provider, Xcel Energy, has committed to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. There’s been less progress to date in the transportation sector, the state’s second-largest emissions source, but Representative Chris Hansen, a Democrat from Denver and an energy consultant, says that will soon change as technological advances allow electric vehicles to become cheaper than gas-powered cars.

“We’re at the start of that transition right now,” says Hansen, an Oxford Ph.D. who wrote his dissertation on electricity reform in India. “EVs are at a price point that is ready to challenge the internal combustion engine. I think we will rapidly decarbonize the transportation sector, and be able to do it without a mandate. No one mandated that we get rid of horses; it was just a better option for the customer.”

In a report released earlier this year, Colorado officials estimated that after decades of steady growth, statewide greenhouse gas emissions are falling, albeit slowly. Much deeper cuts will be needed over the next ten years if the state hopes to meet its 2030 emissions goal, and many activists remain unconvinced that the state is doing enough.

“Certainly there has been some progress,” says 350 Colorado’s McNamara. “That’s great — we need to reduce emissions. But my concern is that we’re not looking at the root cause.”

Nearly all of the climate policies Colorado has enacted to date are so-called demand-side policies, which seek to reduce emissions by encouraging the use of clean energy and lowering demand for fossil fuels. Lawmakers have been far less willing to fight climate change by restricting the supply of oil and gas, and their reluctance has frustrated climate activists who see oil and gas production skyrocketing as scientists deliver increasingly urgent warnings about the need to drastically cut emissions.

“We’re still seeing the tendency to conduct business as usual,” says McNamara. “People still want to push this back, five, ten years into the future. And we’re hearing from the [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] and many others that we don’t have the luxury of that time anymore.”

Advocates for supply-side climate action — who envision a “managed decline” or phase-out of oil and gas extraction — point to evidence that such measures are necessary to prevent the industry from locking in catastrophic levels of warming. In a report published in January, Stockman and his fellow researchers at Oil Change International found that the oil and gas remaining in the world’s already-developed reserves are more than enough to exceed its “carbon budget,” the maximum allowable amount that could be emitted and still meet IPCC targets. A study released earlier this month by Carbon Tracker, a London-based nonprofit, found that major fossil-fuel companies have invested more than $50 billion since 2018 in new projects that are inconsistent with those goals.

“Every time we drill a new oil and gas well, we are making it harder to keep within the carbon budget,” says Stockman. “It’s hard to say whether, in a particular area, do you shut in those wells? Do you let those wells continue to produce until their natural depletion? It’s hard to say how you micromanage that. But we’re absolutely at the point where drilling new wells is counter to solving the climate crisis.”

While SB 181 doesn’t explicitly mention climate change or greenhouse gases, it does direct state regulators to “evaluate and address the potential cumulative impacts of oil and gas development.” Activists say they will push COGCC regulators to make sure those “cumulative impacts” include climate change, and Gibbs says the agency will consider it. But for now, at least, climate-focused efforts to restrict new oil and gas development don’t seem likely in Colorado.

“I don’t see that as the most productive policy pathway,” says Hansen. “We have to methodically work through: What are the cheapest ways to reduce carbon? We’ve got a lot of work to do there before we get to this idea of outlawing some existing economic activity.”

Whether it happens in 2040 or 2060, whether it’s driven by supply constraints or plummeting demand, the end of the fossil-fuel era is coming. The path to a fully renewable electric grid is clear, and technological innovation and market pressures are bringing it closer to reality every day. A report released last month by BNP Paribas, a global investment bank, estimated that within the next 25 years, oil prices will need to be as low as $10 per barrel for gas-powered cars to compete with EVs in the transportation sector.

When the end comes, the industry’s corporate overlords will be fine. They’ll find other businesses to run, different keynote luncheons to network at, new office lounges to hang their hammocks in. Wealthy shareholders will find somewhere else to park their money. Lobbyists will find new clients they can bill for dinner at the Palm.

But for many, many other people, the transition will hurt. It will hurt in Weld County, where property-tax revenue from oil and gas assets makes up a third of the county budget. It will hurt in the gas-rich Piceance Basin, which stretches across much of the Western Slope. There are no easy answers for how these communities will adapt to and recover from what’s coming, but one thing is clear: It won’t be as simple as building solar gardens and wind farms all over the oil patch.

“It’s unlikely that renewable energy will locate in the exact same places as our existing fossil-fuel energy resources,” says Mark Haggerty of Headwaters Economics, a Montana-based research group that studies economic development in rural, resource-dependent communities.

For these communities, oil and gas reserves are more than just an energy source — they’re also an important asset base, and a bedrock of the global financial system. Every drop of oil and cubic inch of gas that’s pumped out of the ground in Colorado is owned by somebody who earns a royalty based on production levels and pays property taxes based on the asset’s assessed value. Renewable electricity generation can provide some value, too — but nobody owns the sun or the wind.

“They’re not going to generate the same kind of returns,” Haggerty says of clean energy projects. “It’s not only the fact that there’s no fuel source, but the actual generation assets will not pay as much.”

In his research, which has focused on timber and coal towns across the West, Haggerty has found that strong local institutions and a willingness to diversify can help communities cope with disruptive transitions, as can uncontrollable factors like proximity to a major city or outdoor-recreation destinations. But few communities he’s studied have been adequately prepared for what hit them, making state and federal assistance a necessity.

“The basic lesson is that successful transition requires communities to be highly resilient and adaptable,” says Haggerty. “The way to achieve that is to ensure that the wealth that is generated from natural-resource extraction is reinvested in your community to build assets that will continue to generate wealth after that activity is over. That’s the trick, and very few places have found ways to be successful at that.”

This declining asset base won’t just be a problem for individual communities. As a growing number of financial experts worry about a potential “carbon bubble,” a scenario in which the value of oil and gas assets crashes suddenly, activists around the world are pushing governments and other institutional investors to divest from fossil fuels. Brett Fleishman, head of global finance campaigns for 350.org, says that Colorado’s largest public pension fund, the Public Employees Retirement Association, is especially at risk.

“PERA is a major, major laggard,” says Fleishman. “They have an outsized investment, comparatively, in the energy sector and the support subsector — oil-field services, pipelines and those types of things.” A bill to require PERA to study the potential risks posed by its fossil-fuel investments failed at the legislature this year, rejected even by many Democrats in a 10-1 committee vote. While the divestment movement has picked up steam globally, most large pension systems in the U.S. have resisted it, and activists fear that it will be retirees and taxpayers who end up paying the price.

“It’s impossible to think that the retirement sector won’t experience some level of a major hit from the energy transition in their current portfolios,” says Fleishman. “Whether it’s a big, dramatic, bank-run-style bubble popping or just that slowly over time, the pension system is more and more stressed and underfunded, and the carbon bubble is a big driver of that.”

Deborah McNamara is a campaign coordinator for 350 Colorado and has worked in the environmental nonprofit sector for over fifteen years.

Anthony Camera

“I think there’s a misconception that environmental advocates don’t care about this, when in fact we absolutely do,” says McNamara. “We’re all looking at how we can make this transition as just and equitable as possible, and make sure that the voices of workers are at the table. Every person that I know that’s part of this movement, it is absolutely a priority.”

Colorado’s Just Transition Office, which won’t start administering benefits until 2025, applies only to the coal industry, which today employs barely more than a thousand Coloradans. There are more than 30,000 directly employed by the oil and gas sector, with tens of thousands more working in related fields. In the long run, there will be new energy jobs to replace them; the state’s clean-energy sector already employs over 65,000 people and is expected to grow by 9 percent this year. But none of that is much comfort to workers in the oil field today, who are understandably reluctant to imagine an end to the industry their families and communities depend on.

“I think electric cars, 100 percent solar and wind, that would be great, but it’s just not feasible, especially not in ten or twenty years,” says Lutz. “It couldn’t happen. Shifting the whole United States to renewable energy — you can’t speed something like that along.”

There are plenty within the industry, from green hats in the oil field to suits in 17th Street boardrooms, who continue to deny the existence of climate change — as do many of the industry’s most ardent supporters at the Capitol. State Senator Ray Scott, a Republican from Grand Junction and former natural-gas executive, claimed on the Senate floor this year that climate change is happening “in the reverse order,” leading to “massive improvements.” But Lutz says that people who deny climate change or insist the oil and gas industry can last forever aren’t representative of the industry as a whole.

“I think there’s more people in the industry that realize — everyone knows oil is a finite resource,” he says. “It’s not like anyone is going to deny that. Obviously, the length of the resources is always up for debate. Some people might say it could go forever, some people might say it could go twenty years. But I think there’s more people that take realistic views of it and know that at some point we’re going to have to change.”

Nearly half a century before the Pikes Peak Gold Rush, the first non-indigenous people to make a living in Colorado began to arrive. They came west across the plains from St. Louis and north along the Rio Grande from Santa Fe, traveling the Louisiana Territory’s mountain streams and winding river valleys in search of a precious natural resource: beaver furs.

Prized by wealthy Europeans who made them into hats, beaver pelts fetched a price of up to eight dollars each, and an experienced trapper could collect hundreds of them in a season. The mountain men, as they would be known in legend, spread out across the Rockies, and for two decades, Colorado’s first and only industry thrived. Trappers and their families built log houses near present-day Pueblo and a series of small forts as far west as Browns Park, places where they gathered, traded with Indians and even tried planting crops and raising livestock.

Then, within just a few years, everything changed. Thousands of miles away, in places few of the trappers would ever visit, fashion trends shifted, and silk replaced beaver fur as the favored hat fabric of the Paris and London elite. The price of beaver pelts crashed to barely more than a dollar each, and the fur trade that had been an economic backbone of the New World disappeared seemingly overnight. Colorado trappers turned to the buffalo robe trade, but not for long. By the early 1840s, nearly all of the trading posts and fledgling settlements that had dotted the Front Range and the Western Slope were abandoned. Thirty years before it would become a state, Colorado had suffered its first economic collapse.

Today, the lanes of U.S. Highway 85 between Denver and Greeley split just south of the town of Platteville, where a reconstructed version of Fort Vasquez, a fur trading post built in 1835, operates as a small museum. Standing on the site of the old adobe fort, which had mostly sunk back into the earth by the time it was restored in 1937, there are oil and gas wells visible in every direction. Traveling Highway 85 takes you past dozens of roadside industrial lots filled with the heavy machinery of modern extraction: trailer-mounted drill rigs, storage tanks, water trucks, cement mixers, fluid heaters, pipes and tubing, pumps and compressors, excavators and downhole tools.

Mile after mile, it’s the undeniable physical proof of the vital economic role that oil and gas plays in Weld County and beyond. If the world hopes to stop climate change, it will all have to disappear, or be repurposed, or simply sit there and slowly decay in the sun like the old adobe trading posts. And the question of what happens to all the people whose work helps power the modern world will have to be answered sooner or later.

“Everybody wants to just put this off,” says McNamara. “The tendency is to just put it off, including the need for a just transition for workers. And who’s going to be left holding the bag? It’s going to be the workers, it’s going to be people [taking] a loss in their pension funds, it’s going to be impacted and marginalized communities and people of color. And that’s what’s so frustrating.”

On September 20, activists around the world plan to hold the largest day of climate-change demonstrations ever, striking and rallying at thousands of events in more than 150 countries, with at least eleven events planned in Colorado. Led largely by youth activists, the Climate Strike movement is calling for a “rapid energy revolution” and “climate justice for everyone” — and an end to new fossil-fuel extraction.

“Part of what we’re doing is calling on the decision-makers and the people who have the power right now to actually do something about it,” says McNamara. “It appears that delay is the tactic right now. And it doesn’t have to be like that.”