Nearly a year later, some neighbors are unhappy with Argow’s new tenant, a sober-living facility for recovering addicts called Emerson House that opened in February.

When Argow notified his neighbors of his plans to rent the home to Emerson House operator Brice Hancock, his relationship with many of them soured. Some felt that he was putting the integrity of the neighborhood at risk.

“It broke my heart to have this happen with Kent. Everybody was tremendously disappointed,” says Jim Wiseman, a friend of Argow’s who has lived in the neighborhood for 41 years.

Argow and Hancock maintain that they are doing a good thing by helping recovering addicts. Still, residents of the San Rafael Historic District, which is in Five Points, have been fighting to overturn Hancock’s zoning application. They cite safety concerns, both for neighbors and tenants, and argue that the home will hurt property values; they also note that there are a number of similar facilities nearby, including other residential-care facilities and a hospital, and say that Emerson House contributes to the “institutionalization” of the neighborhood.

Denver Community Planning and Development didn’t find merit in the neighbors’ arguments against the home, however. On July 30, Steve Elkins, an associate city planner for the city’s zoning administrator, issued a seven-page document that explained the city’s reasons for accepting Hancock’s application for a small residential care facility and contested the neighbors’ arguments, including the point that a nearby liquor store should be considered when issuing Hancock’s permit. Elkins added that decades of research disprove the neighbors’ claim that property values will suffer because of the sober-living facility.

But some neighbors aren’t convinced. A hearing considering their appeal of Hancock’s permit will take place in front of the Board of Adjustment for Zoning in December. Four out of the five boardmembers would have to side with the appeal for it to succeed.

Although the city disagrees with neighbors, it’s this kind of dispute that underscores the reason it created an advisory committee in March to update Denver’s zoning code as it relates to group living, which the committee defines as “residential uses where a group of people larger than a typical household occupy a structure, often with common eating and restroom facilities.” That can include sober-living facilities, artist co-op spaces, homeless shelters and halfway houses.

Argow was set to rent his single-family home on Emerson Street to a group of four people, but they backed out at the last minute. It was January 2018, and the housing market was not particularly lively because of the typically slow winter real estate season.

Argow says he was left scrambling to find a new renter when he received an application from Hancock, who was offering $800 above the asking price. Argow accepted his application.

Hancock operates five sober-living homes in Denver, including Emerson House, under the auspices of Mile High Sober Living. Residents pay $1,250 per month, for shelter as well as access to spiritual advisers and meditation sessions.

In order to house the number of residents he wanted, Hancock had to apply for a zoning permit for a residential care facility. Hancock had not applied for special zoning permits for his other residences; it wasn't until the complaints came in from neighbors about the Emerson House that Hancock applied for special zoning permits for all of his facilities.The process to get the special permit for the Emerson House approved took several months, so Hancock found a temporary solution: He got a boarding permit in mid-March that allowed him to house four people.

The zoning permit for a residential care facility was granted at the end of July, allowing him to increase the home’s residents to eight under the condition that Hancock satisfy the building and fire code requirements needed for housing so many people in a residential care facility. Hancock still has not reached out for the city to come in to the home and perform its fire safety review, nor does he plan on it, arguing that the Fair Housing Act protects him from this step. But by housing eight people without having the building inspected for fire safety, Hancock is violating city laws, according to zoning administrator Tina Axelrad, zoning administrator for the City and County of Denver.

Hancock does not accept people who are court-ordered to live in a sober home, nor does he accept sex offenders or violent felons. Residents must take two drug and alcohol tests per week; a failed test is grounds for expulsion.

Hancock himself has been in recovery since 2013 and considers his work to be his God-given purpose. But at least 42 people disagree. That’s how many emailed Denver Community Planning and Development to oppose the facility during the public-comment period of Hancock’s permit application process, which lasted from the end of May to the beginning of June.

Some complained that too many cars owned by tenants and their visitors were parked on the street. Others worried that the short-term nature of the leases would prevent tenants from investing in the neighborhood.

Members of the Old San Rafael Neighborhood Organization assembled a neighborhood forum toward the end of January to discuss the home and invited Argow and Hancock. But by the end of it, both sides agreed that little progress had been made to address their issues. Hancock and Argow felt that opponents were shouting them down, and residents say Hancock didn’t seem sympathetic to their concerns.“The city made the rules, but they seem so reluctant to enforce them because they’re afraid of being sued.”

tweet this

“The sober-living deal probably would have been okay if [Hancock] had worked positively with the neighborhood,” says Albus Brooks, Denver city councilman for the district, about the meeting. “[But] there was a very bad interaction in the beginning. It’s been pretty ugly since.”

For his part, Hancock says he felt attacked during the meeting and so just shut down in the middle of it. He thinks neighbors are opposing his facility for reasons based in “negative stereotypes of drug addicts and alcoholics.”

“I don’t think they want them there,” he says, adding that he believes they want to help people in recovery “as long as it’s not on their block.”

Tenants of the household understand some of the concerns. Kate M., a recovering opiate addict and alcoholic, has lived at Emerson House for three months. She feels that it’s only natural that neighbors would first ask, “Are they going to be using at the house?”

“I get it. When you first hear about it, it’s a little scary,” says Kate, who asked that we not use her full last name. “But we’re in recovery, not addiction. All those thoughts they had are not the case. Anyone that has been on this block and seen us living would say, ‘Oh, I was wrong. They’re normal people.’”

Opponents say their fight isn’t rooted in stereotypes.

“We’re not a bunch of bad guys,” says Wiseman, who also wrote to the city. “We’re just concerned about the unregulated nature of these things and the threat to the fabric of our neighborhood.”

Hancock’s permit allows up to eight people to live in a single-family home. Neither the city nor the state requires owners of sober-living homes to be licensed.

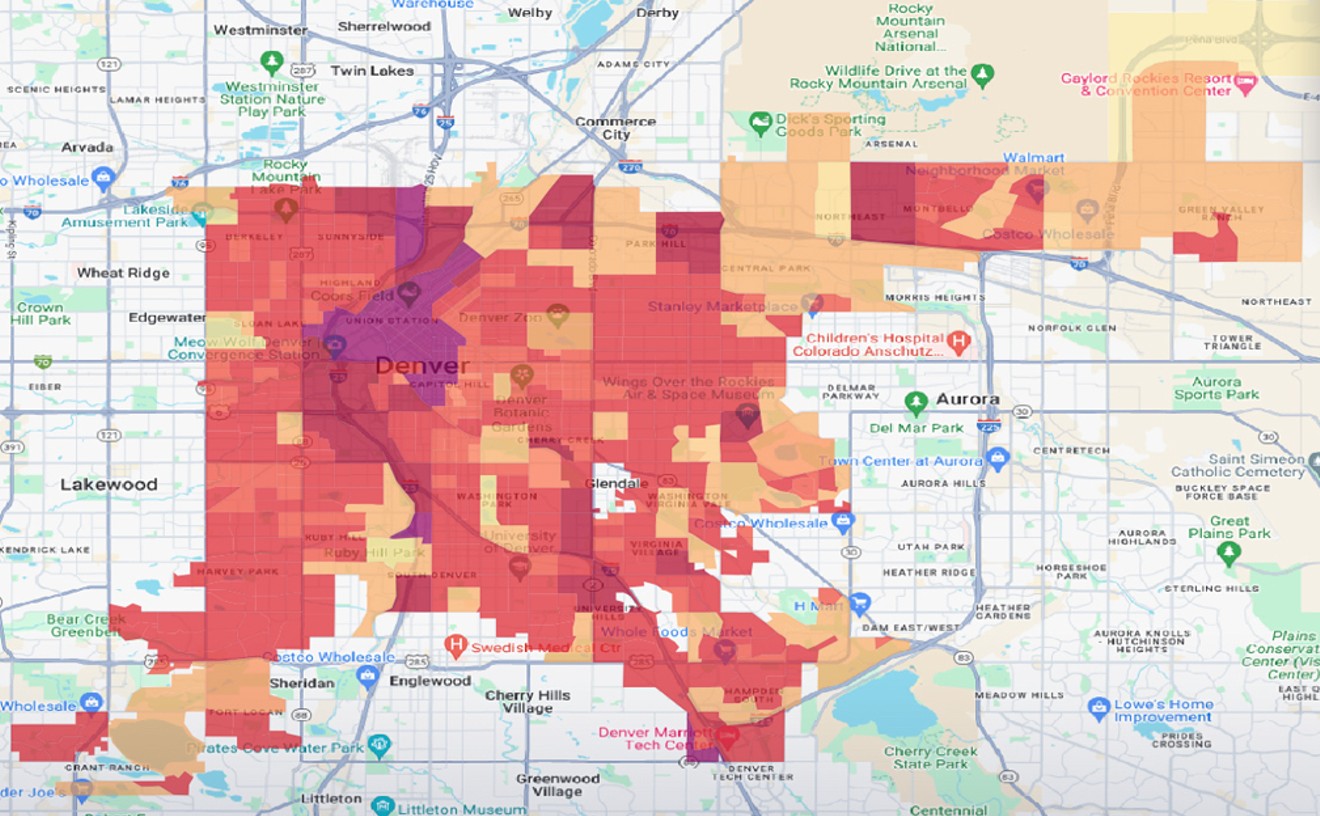

During the permitting process, the city conducted a search to determine how many other residential-care facilities were in close proximity to Emerson House. It found no residential-care facilities within a 2,000-foot radius of the home, but when using a 4,000-foot radius search, five were found.

Sofia DeAngelis, who is in recovery, manages Emerson House, where she lives with seven other women.

Anthony Camera

“There’s no one number that is a tipping point for making a neighborhood institutionalized,” says Axelrad.

An August 10 report by Community Planning and Development shows that the Five Points neighborhood has eight residential care facilities, the second-highest number among Denver neighborhoods.

Neighbors point to this data set — and not what the city considered to permit Emerson House — to support their arguments against the facility.

“When other parts of the city do what we have done in housing and support the special-needs population and the low-income, only then should you come and ask us to do more. Because we’re doing our part and have done so for decades,” says Marty Jones, a San Rafael resident.

“The city made the rules, but they seem so reluctant to enforce them because they’re afraid of being sued,” says neighbor Kyle Jones (no relation to Marty).

The zoning code is not only absent of specific guidelines for permitting such facilities, but the city must also consider the Fair Housing Act, which prohibits discrimination against protected classes, which include those in recovery. If the city had denied Hancock’s permit, it could have opened itself to legal action.“Anyone that has been on this block and seen us living would say, ‘Oh, I was wrong. They’re normal people.’”

tweet this

“Small group homes are really intended to have an easy time finding their way into our residential neighborhoods, primarily because we have been told to do so by the federal and state governments,” Axelrad says.

At an advisory committee meeting on October 8, Axelrad explained the city’s unease when permitting residential care facilities.

“It makes staff, to be brutally honest, extremely nervous, so what you get is erring on the side of being conservative and not laying open the city to any viable Fair Housing Act claims,” she said.

The advisory committee, which comprises Denver City Council members, professionals working in various group-living industries and neighborhood representatives, is working to clarify the zoning code’s treatment of such facilities, specifically the section on residential-care facilities that aims to “prevent the ‘institutionalization’ of residential neighborhoods by concentrating Residential Care uses so as to allow all residents, including the special populations, to reap the benefits of residential surroundings.”

Neighborhood representatives on the committee want the city to define “institutionalization,” but the zoning administrator’s office has not yet opted to do so. If it does, the definition will have to comply with federal and state mandates that dictate how to treat protected classes.

“It’s not a term that has any meaning in zoning,” says Brian Connolly, a local lawyer specializing in land-use and Fair Housing Act issues and author of a book on group homes. “What institutionalization refers to has a meaning that comes from social and medical science. It references a time when people with disabilities and people with health issues were put in state-run institutions.”

Hancock says he has taken some of the neighbors’ concerns into consideration. Some were concerned about the house only catering to men, so he made the house for women only.

But even gestures such as this aren’t enough for neighbors, who are leaving it to the Board of Adjustment to decide the fate of Emerson House.

“We don’t necessarily expect to win; it’s an uphill battle,” Wiseman says. “But we feel compelled to make a statement to the city and anybody else who will listen that this needs to be dealt with.”

Meanwhile, the group-living advisory committee will continue working to develop recommendations for the Denver zoning code update, a process they hope to complete by fall 2019.

And the state legislature is working on its own regulations for sober-living facilities as part of its fight against the opioid epidemic. The Opioid and Other Substance Use Disorders Study Committee has drafted a bill, set to be introduced in January, that will require sober-living home operators to be licensed by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment.

In the meantime, tenants like Kate M. are just happy they can recover in a pleasant neighborhood in the heart of Denver.

“I’m just grateful that this is available and that I don’t have to go to a place that I’m not comfortable living in,” Kate says.

This story has been updated with new information about Hancock's permitting.