Despite blustery comments from President Donald Trump on Twitter, it’s now difficult to refute that Russia influenced the outcome of the 2016 presidential election. The 37-page indictment that emerged from Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s Russia investigation on Friday, February 16, was a political bombshell; the stunning document charges that three companies and thirteen Russian nationals carried out a deliberate misinformation campaign designed to sow division in the United States and sway voters toward Trump. Over the weekend, national news outlets reported at length on the vivid narrative laid out in Mueller’s indictment, some expressing shock that it described the Russian campaign as going as far back as 2014. Two of the thirteen individuals in the indictment had visited Colorado that June, working to collect intelligence in the purple states that might decide the 2016 election two years hence.

Who knew that the Russians had been at it that long?

Well, Westword did. Our July 20, 2017, cover story, “Red Alert,” described how Russian cyber campaigns against the United States go much further back than 2014. In fact, the very first proven instance of Russian-sponsored cyberwarfare occurred right here in Colorado in 1996!

The invasion began at 8:30 p.m. on October 7, 1996, and lasted until the early hours of the morning, a time when no one would notice that infiltrators had stealthily slipped through the defenses of a computer at the Colorado School of Mines. Once inside the machine, the hackers binged on data, consuming sensitive information from around the globe.

The next morning, computer technician Kathleen Lamb checked her email inbox and learned of the attack. Although she occasionally had to deal with hacks and breaches of the university’s computers from students and other aspiring hobbyists, she now had a slew of emails from network administrators around the country — and even a few outside of the United States — informing her that a computer located on the Mines campus in Golden had been used to probe or access their networks in a suspicious manner.

Hackers had used the corrupted computer in the engineering building to go after data at the Department of Defense and NASA. But it would be years before a crack cyber-forensics team at the FBI, which dubbed its investigation “Moonlight Maze,” would manage to trace the attack all the way to the Kremlin.

The twisting and turning investigation involved cat-and-mouse games between the federal agents and their slippery targets. And incredibly, one of the ways that the FBI sourced the attacks to Russia was by installing a tracing device on another breached computer they managed to discover in Colorado — this time at the Jefferson County Public Library — that provided forensic details about the origins of the cyberattacks.

Like IT technicians at the Colorado School of Mines in 1996, network administrators at the JeffCo Library didn’t know that they were being attacked from Russia — or what the FBI was up to when agents came knocking. “I’m a nosy person, and I talked to [the FBI agents], but there were definitely limits to what they could say,” one of the library’s techs, Robbie Johnson, told us. “They were not going to talk about a lot of stuff — that was clear from the onset.”

The FBI’s clandestine investigation eventually took federal agents to Moscow in April 1999, where the Americans made up an excuse to meet with top Russian officials. The Russians got the Americans drunk on vodka at a dinner function in the hopes of finding out what they were really up to. As the evening took a bawdy turn, one Russian general even stuck his tongue into the ear of a female FBI agent.

But the agents were not deterred. While in Moscow, they finally found the information they were looking for: The Internet service provider used by the Russian hackers on computers such as the ones at Mines and the Jefferson County Library also served the Russian government.

That discovery established a direct link between the attacks and the Kremlin.

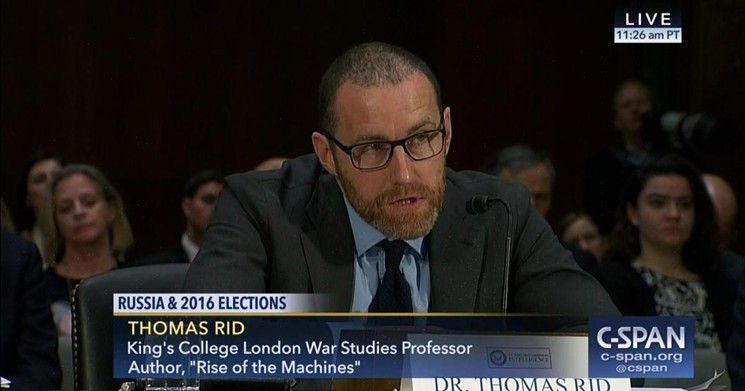

Even after the feds wrapped up the Moonlight Maze investigation, cyberattacks and misinformation campaigns by the Russians did not stop — and the American people are only now learning about many of them. The 1996 incident at the Colorado School of Mines, for example, was not known to the public until a British researcher and professor named Thomas Rid found out about it through an open-records request and wrote about the incident in a book that was released in 2016.

“The future began with Moonlight Maze,” Rid told us. “Espionage now looks more like Moonlight Maze than anything that we saw during the Cold War. It really was the beginning of the new era, and it’s never really stopped.”

After the release of his book, Rid began investigating Russian intelligence operations around the 2016 election. In June 2016, he was one of the first experts to publicly call out Russia as being behind cyberattacks disrupting the presidential campaign of Hillary Clinton. And on March 30, 2017, he was invited to testify before the Senate Select Intelligence Committee at its first open hearing on Russian interference, an appearance he called “one of the craziest events of my entire career in terms of its visibility.”

Before the committee, Rid discussed Moonlight Maze and its direct relevance to Russian cyber operations that aimed to undermine the 2016 election. “In the past twenty years, aggressive Russian digital espionage campaigns became the norm,” he told the senators. “The first major state-on-state campaign was called Moonlight Maze, and it started in 1996.”

Rid isn’t surprised by the revelations about the Russians that have continued to spill out since he testified almost a year ago.

So while some people were shocked by the contents of the Mueller indictment, it just represented the most recent actions in more than two decades of Russian-sponsored meddling. Back in April 2016, then-presidential candidate Donald Trump called Colorado’s election process “rigged” — a claim that Secretary of State Wayne Williams vehemently denied. (After the Mueller indictment was released, Williams did another review; on February 20, he reported that no compromises were found. "What is not in the indictment is any mention that Colorado's voter registration system or voting and tabulation machines were compromised in any way," says Williams.)

But as the Moonlight Maze probe showed, it can take a long time to figure out exactly what the Russians are up to. And over the years, that country's operatives’ tactics have only become more refined, maybe even to the point of being able to tip a presidential election.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]