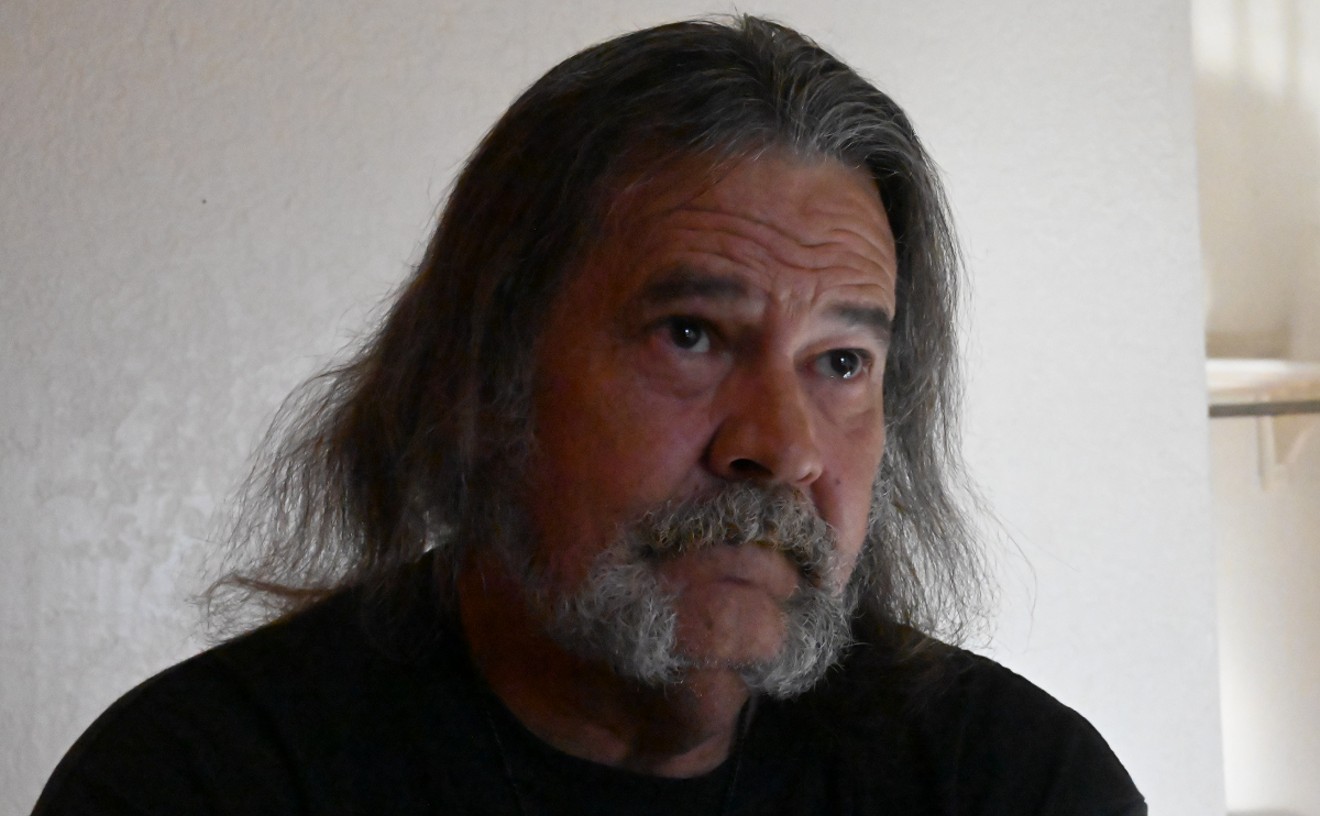

After her husband was sentenced to prison for a long, long time, Beth Stone resolved to do what she could to keep the relationship alive. She moved to Cañon City so she could visit him regularly at the prison complex east of town. And she writes to him just about every day — personal notes in bright inks or colored pencils, letters decorated with hearts, homemade cards.

"I don't do it because it's my job," Stone says. "I do it because I love him, and I want him to feel special when they call his name for mail."

But because of a drug war being waged behind prison bars, Stone and thousands of other family members of state prisoners are facing tough new restrictions on ways they can communicate with the incarcerated. Starting March 1, the Colorado Department of Corrections will no longer allow inmates to receive postcards, greeting cards, or "any items containing drawings," according to one employee's summary of the new policy. Prisoners first learned of the changes from a short bulletin over their TV sets, and word has gradually filtered out to prisoner families and advocacy groups, which have raised a host of questions about the crackdown.

Officials say the move is necessary because of the ease with which illicit drugs can be dissolved into certain types of mail and smuggled into prison. Liquid meth has been a periodic problem, but the chief culprit of the moment is Suboxone, a prescription drug used to treat symptoms of opioid withdrawal that can also provide a euphoric high.

Suboxone is typically dispensed in super-thin strips, similar to breath strips, and the thinness makes the drug ideal contraband; it can be concealed in the folds of greeting cards or under crayon drawings and glossy postcard images. In 2015, New Hampshire's state corrections system began rejecting greeting cards, drawings and colored paper in an effort to halt Suboxone smuggling. It also banned kissing between inmates and visitors to prevent spouses and significant others from slipping prisoners Suboxone along with some tongue.

CDOC spokesman Mark Fairbairn says his agency intercepted 28 pieces of Suboxone-laced mail addressed to inmates last year. The most recent reported incident occurred earlier this month, when mail inspectors at the Colorado State Penitentiary uncovered a cache of Suboxone in a package of "legal mail" sent to a prisoner. The number of known incidents is far lower than in several other states — Maryland's prison system, for example, has reported seizing thousands of Suboxone strips a year. But quite apart from its Suboxone problem, Colorado has the sixth-highest rate of fatal drug and alcohol overdoses by prisoners, according to a state-by-state analysis of fourteen years of data by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

The CDOC plans to photocopy each piece of disallowed mail, destroy the original, and provide the black-and-white copy to the prisoner, "so they will still receive the correspondence from their loved ones," Fairbairn says. But family members say a photocopy is a poor substitute for the actual drawing by a son or daughter or a homemade Christmas card. They suggest there are better, less labor-intensive options than photocopying tens of thousands of pieces of mail, such as sophisticated mail screening machines that use hyperspectral imaging detection systems.

"We are exploring options to detect dangerous drugs," Fairbairn responds, "but at this time a photocopy of the mail is the most effective and cost-effective method available while still allowing the offender to receive the message."

Families of Colorado prisoners have other, supposedly more efficient ways to reach out to them, including a fee-based email service provided by JPay and a similar service that comes with the "free" electronic tablets that have been provided to CDOC inmates by a private contractor. Stone says the services are often no faster than regular mail — emails that are supposed to be reviewed and delivered in a few hours can take days to reach the recipient — and a lot more impersonal.

"The tablets are super-crappy," she says. "With mail, you can personalize it. You can use different colors. If you go on a trip, you can pick up a postcard and write, 'Miss you. Wish you were here.' You can add hearts. If I put a heart on JPay, it ends up as a question mark."

Prisoner advocacy groups have long maintained that inmates' families have been unfairly blamed and penalized for contraband problems behind bars. ("The mail is not how most of the drugs get in," one ex-offender recently told Westword. "It's staff.") Studies also suggest that inmates have a better chance of rehabilitation if they remain connected to a supportive family unit. Yet the trend within corrections systems has been to increasingly isolate inmates in their own cybershell, promoting video visitation over face-to-face visits and the "convenience" of easily monitored email over the intimacy of snail mail.

Stone's husband, Ryan, is less than three years into a 160-year sentence, the result of a 2014 carjacking and high-speed chase that seriously injured a state trooper. Methamphetamine use, everyone agrees, played a large part in his crime. And now that he's serving his time, other people's drug use is messing with his remaining connections to the outside world.

The idea that her husband is going to get a drab photocopy of anything creative that she sends him doesn't appeal to Beth Stone. "To me, it's not even worth sending a card anymore," she says. "It's almost like you're living in Pleasantville, where everything has no color."

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "leaderboardInlineContent",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "tower",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

}

]