Black Cube's work is proudly decentralized. Curator and director Cortney Lane Stell finds organizational inspiration in aspen groves, grasses and other rhizomatic biological structures that take root horizontally and spread. In her case, that's been around the globe, though she and Black Cube still call Denver — and, most recently, an industrial building in Englewood that she's dubbed Black Cube Headquarters — home.

The wandering museum has elevated such mid-career local luminaries as Laura Shill, Joel Swanson and Derrick Velasquez, helping to fund some of their riskier creative endeavors. It has also brought attention to Colorado from the international art world, forging relationships with arts organizations and cultural workers abroad.

Black Cube was founded by artist and philanthropist Laura Merage and the David and Laura Merage Foundation — whose money came, in part, from the family company that created Hot Pockets. Merage also helped found RedLine Contemporary Art Center in 2008. While RedLine has supported Denver’s arts community and created a world-class, non-commercial exhibition space in Five Points, Black Cube has brought artists from around the world into the Rocky Mountain region while exporting homegrown talent to other communities. Both institutions play an outsized role in Denver's arts scene, often producing more vital work than better-funded behemoths like the Denver Art Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver.

Now Stell is celebrating the launch of a gorgeous book documenting the sprawling work of Black Cube’s first five years — a mix of artist residencies, special projects and ambitious shows in venues as small as Understudy and as far-reaching as the Venice Biennale. Dubbed A Nomadic Art Museum: Black Cube 2015-2020, the handsome coffee-table tome memorializes dozens of the institution’s projects, many of which were temporary, performance-based and responding to ever-changing landscapes.

The book helps explain Black Cube’s work, which is harder to pin down than that of a traditional museum. Nearly all of the organization's projects take place in public spaces, from digital billboards and the alleys off the 16th Street Mall to the Colorado Capitol and the U.S.-Mexico border. Throughout the year, Stell works on an ever-changing roster of projects, each offering unique possibilities and obstacles.

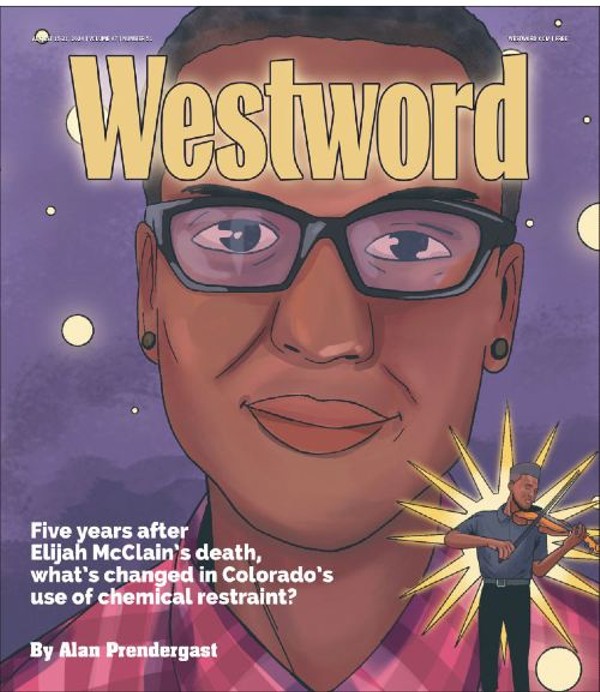

Cortney Lane Stell is ready to greet the worldwide future of contemporary art.

Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum

“That’s one model, and it’s really fantastic,” says Stell. “But it’s omnipresent in the world. At the core of Black Cube was thinking to turn that model on its head. What happens if you go to that community? What happens if you're a shapeshifter in ways and mold to the artist’s vision and the community’s? That’s a core aspect to this organization. This organization operates really differently as it relates to each different artwork.”

An ever-shifting itinerant identity has made securing the kind of funding that fuels other local cultural groups more challenging. Because of its nomadic nature, Black Cube has not received Scientific and Cultural Facilities District grants. And when it comes down to it, Stell would prefer money to come directly from the communities where her artists are working.

“When you partner with funding from that community, you bring in that community more,” she says. If outsider foundations were largely paying for exhibitions, “it would seem more like we were plopping art instead of integrating into that community.”

Much of the work that Black Cube produces doesn’t necessarily look like art. And along the way, Stell has struggled to tell the organization’s story through blog posts, behind-the-scenes videos, and even door-to-door informational campaigns.

The book ties the projects together and demonstrates how Black Cube's efforts are more than just a string of fleeting, one-off experiments. A curatorial vision runs through the museum's work, and the book helps clarify the group's political, social, aesthetic and cultural mission while celebrating a staggering array of accomplishments in such a short time. With compelling essays by Stell, Merage and art critic Paddy Johnson, A Nomadic Museum is as smartly conceived as the best of Black Cube’s projects — and those have been impressive in both scale and breadth.

Andreas Greiner, Monument for the 308, on view at the Denver Central Library, curated by Black Cube and co-produced with the Denver Theatre District.

Third Dune Productions.

The library, Stell says, models the best of how public spaces can function.

“I am so endeared to the library,” she explains. “It is what every museum should be. They are so open to supporting the community. They really try to encourage curiosity, and they meet people where they’re at, from bathroom use to mental health. That’s an organization I am deeply motivated to support.”

And as Stell tells it, the currently closed library has been one of the few purely public spaces in town.

“You have to be a consumer everywhere,” she says. “I’ve done projects in Union Station. That place is heavily policed; it’s not the same. It’s such a different approach at the library. We’re all human. We all deserve dignity. You meet people where they’re at, as opposed to Union Station, where it’s more of a judgmental gaze.”

Stell has also produced large-scale art projects in unoccupied spaces slated for demolition and construction. "Unclassified Site Museum," an archeological dig of a fictional lost city by SANGREE, the Mexico City-based duo of René Godínez-Pozas and Carlos Lara, was installed at the former Market Street bus station downtown. Stell secured the site from arts philanthropist Mark Falcone, CEO and founder of Continuum Partners, who was working on developing a new high-rise where the station once stood. But having his permission wasn't enough; she also wanted people who used the area to believe in the project. So she built a relationship with some men experiencing homelessness who would go to the station to feed pigeons, as well as several skaters who used the space as a skate park. Both groups took ownership of the project and helped keep it safe.

Among the toughest sites Stell has secured was the Denver Wastewater Management campus, where Institute for New Feeling, an artist collective, took on questions of technology, wellness, privatization and capitalism, launching its own brand of bottled water with an installation called "Avalanche." Stell recalls that it was difficult to get permission, but once she did, "everyone at Wastewater was very supportive about a weird request to do a bottled-water performance.”

That's what she loves about Denver: The city is still wide open to collaborations between unlikely partners. “At a lot of organizations, it can be difficult to get your foot in the door about conversations,” she says. “But almost everyone, once you have that foot in the door, is incredibly collaborative and supportive.”

And even as Denver’s art world becomes increasingly competitive, entrepreneurial and driven by a compulsion to entertain, Stell is excited about the potential for artists here to experiment with form and concept.

“I see more opportunities for boundaries and collaborations to be blurred, for institutions to welcome people, artists and cultural workers to their spaces — for people to see a double bottom-line benefit to engaging the cultural sector," she says. "By stimulating our community and our cultural scene, you bring a vivaciousness to our community, to places that often don’t invite the public or places that do, such as alleyways or tiny mining towns or municipal facilities. I think there is a lot of openness in our community for more collaboration and exploration.”

To order A Nomadic Art Museum and learn more about the museum, go to Black Cube's website.