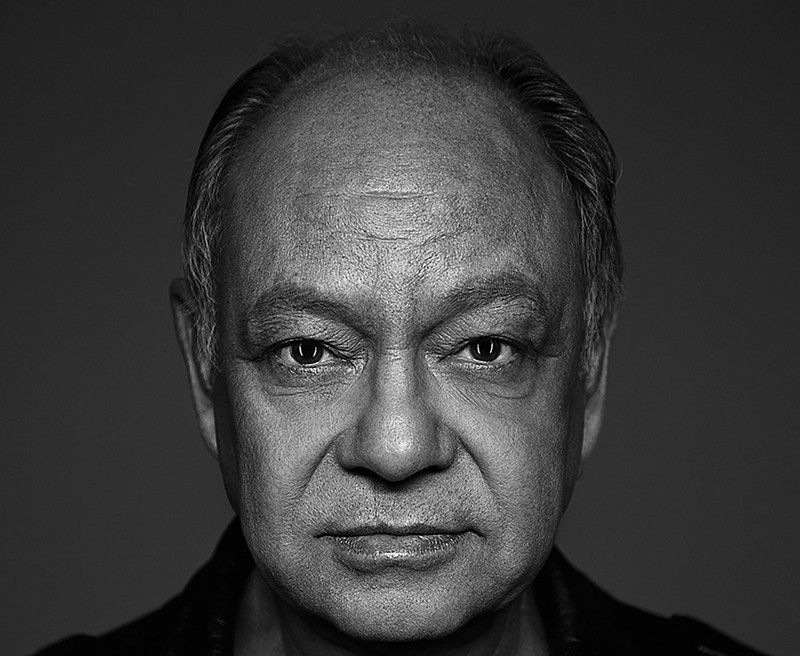

Cheech Marin isn’t just a comedian, movie star and ’80s-era pot icon. He’s also one of the most notable collectors of Chicano art in the world today. Two things attest to this: his upcoming museum in Riverside, California — officially called the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art, Culture & Industry, but already nicknamed "The Cheech"; and his traveling show, Papel Chicano Dos: Works on Paper From the Collection of Cheech Marin, now on display at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center.

“I want to encourage everyone in Colorado to come and see it,” Marin says. “It’s a wonderful collection of works on paper by amazing Chicano artists. This is our second volume of it, and we’ve traveled all over the country and played over fifty museums with this collection. It’s unheard of — a lot of museums don’t like showing private collections. But people just love it.”

We talked with Marin about the show, how his collection started, and how his personal history prepared him strangely and perfectly for having his name grace an art museum.

Westword: Tell us about the project that’s creating the Cheech in Riverside, opening in the fall of 2021. How did that museum come to exist?

Cheech Marin: I was doing a show at Riverside, and it was a big hit — like three times bigger than any show they’d had there before. They were looking for how to repurpose this building, the town library, because they’d committed to building a new library. The town manager saw the success of the show, and he went to the city council and made a proposition that they’d offer the building for the collection. And they agreed. So it was something that came to me, like a bolt from the blue, like it fell out of the sky right on top of me.

I guess that’s how a lot of good things happen.

You know, that’s my belief. People always talk about being hit by dumb luck. Well, if you stand in an intersection with a fluorescent suit waving your hands back and forth for years, yeah, you might get hit by dumb luck.

It must be both weird and super-cool to all of a sudden, after all these years of collecting, have a museum named for you.

All I can say is that it’s about damn time [laughs]. It’s a dream I didn’t really dream. It didn’t seem plausible. I couldn’t build a museum. And then this fell out of the sky. The only thing I can think is that it’s supposed to happen.

And Riverside is such a beautiful, historic city. In the 1880s, it was the richest city per capita in the United States because of citrus. Oranges, lemons, tangelos for valleys and valleys. They brought the railroad in there, and it supplied the rest of the world with citrus. At the same time, they commissioned a lot of buildings, this beautiful mid-century library being one of them. If we had a list of the ten most beautiful modernist buildings, this would be on the list.

Talk a little about the collection as a whole — you have over 700 pieces now?

I’ve been a collector all my life. It was always something: bottle caps, baseball cards, whatever. I had a penchant for collecting, and it really all started when I was collecting Art Nouveau, and it got to be really expensive. So I was looking around for something else, and I got introduced to some Chicano painters at a gallery in Los Angeles, and that’s where I got exposed, where I first thought, “Hey, these painters are really good, you know? Why aren’t they getting any shelf space?" I started collecting, and kept collecting, and in a pretty short time, I’d amassed a fairly big collection.

How did you move from collecting the work to showing it?

I had friends come to me, friends from the art world urging me to do it. It doesn’t do any good under the bed, or in storage, you know? But easier said than done. In order to show it, you had to go out and find the people and places that wanted to display it, that had the money to display it.

People I knew from the art world, these guys with large collections of something, they’d ask me how I found my sponsors: How did you do it? And I'd tell them, “Well, the first thing you do is you go out and be a very famous internationally known movie star. For like fifty years. Do that first, and then come back to me and I’ll tell you the second step.”

But even then, I had museum curators hesitant about putting up the show. Nobody wants to put their head on the block, you know? So I’d tell them: The thing is that I have this collection because you don’t. And there was never any answer to that. I went to the Smithsonian: “I have this collection because you don’t.” I went to LACMA [Los Angeles County Museum of Art]: “I have this collection because you don’t.” They finally got the picture, and I ended up getting sponsors. From the time I started thinking about putting all this on tour and organizing and getting funding, that process was ten years, going to every corporate boardroom in America and doing my dog-and-pony show.

That must have been a whole new experience.

Yeah. It’s weird, because we were almost sponsored by the Army. But that would have just pissed everybody off.

The Army?

Yeah, the Army is the number-one hirer of Chicanos in the country. So you know, they were pretty anxious to do it, but in the end, I didn’t want to piss anyone off that much. I started this as an outsider. I didn’t have a Ph.D. in Chicano studies, or painting. I was just a guy with a collection that I wanted everyone to see because this was the kind of collection that has not been shown.

Do you have a favorite piece in the collection? Is that even a fair question?

No, it’s not a fair question [laughs]. Whichever painter is nicest to me at the time, maybe. No, it’s like choosing your favorite child, you know? I’m sure you have one, but you’re not going to tell anybody about that. There are so many paintings. It’s been a long and involved trip, and it’s still going. I’m still collecting pieces to donate to the museum.

So what’s the newest piece?

Just the other day I bought one of those pieces that first got away. You learn as a collector as you go along how to refine your eye so that when you see something really good — and you can afford it — you go ahead and get it right away. Because if you go around the show, thinking, "Oh, I’ll come back to it," it’ll be gone by the time you do. This was one of those, a painting by Benito Huerta, a beautiful giant work on velvet, a take on Picasso’s "Les Demoiselles d’Avignon." It’s a monumental piece. And that’s what happened to me, I walked away and it sold. Just recently, the man who bought it died, and he passed it on to his son, who’d heard I liked the piece and wanted it, and he contacted me.

Where in your past did the art appreciation come from? Someone in your family?

Inadvertently. I had nobody in my family who was an artist or a painter. They were all blue-collar Chicano working-class. My dad was a policeman, my uncles were either upholsterers or worked for the railroad. But they had these really bright kids. My cousins and I applied ourselves academically, most of us got scholarships, me not included. One cousin got a full ride to Harvard, and he became the first Ph.D. doctorate in Chicano studies from Harvard University. We all went to Catholic school, so we had that liberal education in common. When we were kids, one cousin assigned all of us a topic to go out and find out about it and report back to the group. He turned to me and said, “Cheech, you go learn about art.” And I said, “Well, okay, how do you do that?”

So I went to the library and looked at all their art books. I couldn’t even take them out; I had to look at them there. It was my ritual every Saturday: After I would get up and do my chores, I’d go to the library. After a while, they knew me and knew I was coming, so they’d set out art books for me. I realized that it was coincident with Catholic education, because liturgical art was art.

That makes sense.

Yeah, I think that was one of my first inclinations toward art. I remember going to Mass when I was young, like seven, maybe, and it took forever, you know, it was going on and on, and I remember looking up at the ceiling. It was painted, and there were saints kind of walking around in the clouds wearing sheets, and I’m looking at it and I was like, “Why are they barbecuing that guy in the corner? What’s up with that?” [Laughs.] So right away I was intrigued. That was the beginning. By the time I found the Chicano painters, I knew about art. I knew about what good painting was, because I’d spent all that time going to museums all those years.

You have to see paintings in person, by the way. Because of the quality of the paint; it makes a difference a million different ways. But you only get to truly experience a painting when you see it in person.

Which is what folks will get to do in the traveling show down in the Springs. And you come to Colorado pretty frequently, yeah?

I love Denver. Have a lot of good friends there.

You were just here a while back to visit some dispensaries and promote your own line.

Cheech’s Stash is what we call it now, yeah. It changes every year.

So much of your early career used marijuana as a focus. What’s your take on legalization and how that’s going nationally?

It’s great. It’s like watching an avalanche in slow motion. It’s almost every single state. It’s a movement, and you can stand in front of it, but I wouldn’t recommend it. As soon as Biden gets in, he’s going to nationalize it federally, which is what should be done.

Ever thought about rebooting the old Cheech & Chong films for the 2020s, given the rise of legalization?

You know, we’ve thought about that, but then we lie down and the feeling goes away. People don’t realize what an arduous task making movies is. It involves a lot of sitting in a trailer, and I’ve had it with sitting in trailers. But yeah, somebody was just talking with me the other day about an idea for a Cheech & Chong science-fiction movie. I think that would be great.

That sounds like it would be fun.

Yeah! So now we’re waiting for them to send us ten million dollars apiece, and then we’ll get on board.

You could buy more art for the Cheech.

Exactly, exactly.

Papel Chicano Dos: Works on Paper From the Collection of Cheech Marin runs through June 21, 2021, at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center. Reservations are required; see the FAC website for tickets and more information.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "leaderboardInlineContent",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "tower",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

}

]