When the MCA was founded in 1996, a major goal was presenting important shows dedicated to significant Colorado artists like Richert. However, the MCA, like the Denver Art Museum, has done so far too rarely, particularly in light of all the worthy talent in the area. Putting the MCA back on track is Clark Richert in Hyperspace, which was ably realized by assistant curator Zoe Larkins, who talked with Richert and also researched archives, libraries and other sources in order to tell his story and find all of the art she wanted to include in the exhibit. Though Richert had a mother lode of early works stuck in the nooks and crannies of his house and studio, pieces from the 1980s and ’90s had scattered to the four winds, landing in private, corporate and public collections. Surprisingly, corporate and public collections typically do not have overseers, so in a few cases Larkins really had to work to track down the Richerts she was looking for. Adding to the challenge: Richert himself had trashed or abandoned many pieces as he moved his studio around over the decades.

Psychedelic posters by the imaginary “Clard Svensen” in Clark Richert in Hyperspace.

Wes Magyar, Courtesy of MCA Denver

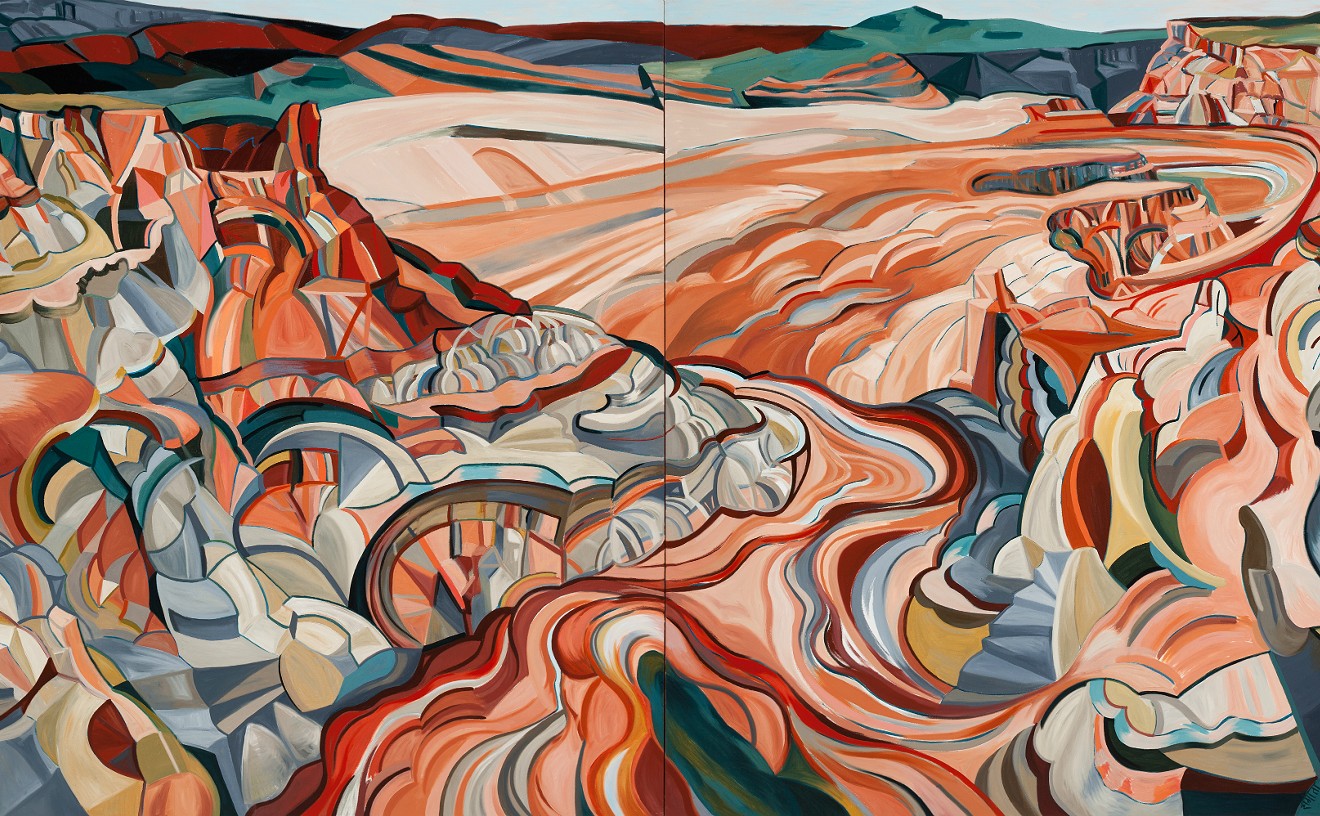

The chronological retrospective at the MCA fills a trio of galleries on the main level as well as the entire second floor of the museum. It begins with “Blue Room,” a painting done in 1964 that’s a geometric rendition of an interior space, with a cruciform defining the picture plane. This play between the depiction of recessive space and the flatness of the canvas’s surface occupied Richert over his career. Sometimes he exaggerates the flatness, at other times the illusion of three-dimensionality, with any number of hybrids in between these opposites. The second gallery holds a revelation: the weird comic book “Being Bag,” done collaboratively with fellow Droppers Gene Bernofsky and Richard Kallweit. While “Being Bag” struck me as an aesthetic non sequitur in the arc of Richert’s oeuvre, its narrative concerns someone passing from one dimension to another, a conceptual underpinning of his work. More on point aesthetically are the glow-in-the-dark patterned posters mass-printed in 1968 under the pseudonym Clard Svensen. I loved them.

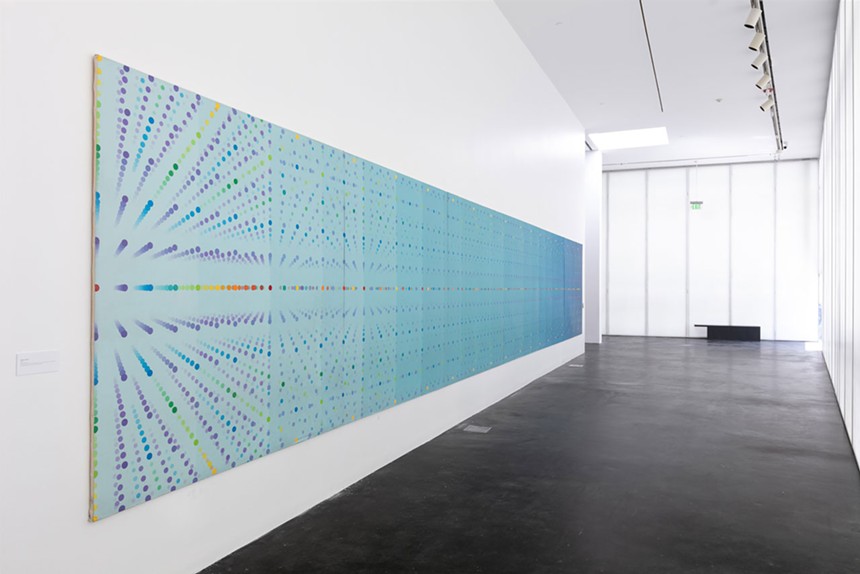

"Horizon Event," a 42-foot long mural created in 1986, in Clark Richert in Hyperspace.

Wes Magyar, Courtesy of MCA Denver

One of the principal second-floor galleries showcases Richert’s paintings from the late ’80s and early ’90s. These hark back to “Blue Room” in that they capture interior spaces, though they’re much more ambitious and complex; Richert populated them with the geometric explorations that had occupied him since his Drop City days, but he employed realism to do it, even rendering a figure in one. By the late 1990s, though, his compositions had gone non-objective again, picking up the threads of his Criss-Cross days. Aside from “Horizon Event,” which anticipates his later minimal depiction of three-dimensionality, the pieces from the past twenty years are generally looser and airier than the earlier pattern works. For these newer paintings, Richert used digital techniques to make his studies, which he didn’t do with the earlier pieces...even if it often looks like he did.

Installation view of the west gallery in Clark Richert: Pattern and Dimensions at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art.

Wes Magyar, Courtesy of BMoCA

Stell conceived of the show as a set of separate presentations exploring Richert’s oeuvre. She’s even restaged a couple of the “droppings,” in particular “Pendulum,” a boot on a rope hanging from the building that was initially done by Richert with Bernofsky before they came to Colorado.

"A.R.E.A." (left) and "Drop City" in Clark Richert: Pattern and Dimensions at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art.

Wes Magyar, Courtesy of BMoCA

In the front section of the east gallery are some unexpected abstract-expressionist works that Richert did in the early ’60s. On the other side of that gallery is a thoughtful presentation on Drop City, with photographs of various parts of the complex as well as day-glo paintings that inspired the psychedelic posters at the MCA. The paintings look even better than the posters, especially since Stell put them in the dark under black lights. The space also includes a non-narrative film Richert did while studying with legendary vanguard filmmaker Stan Brakhage, and a re-creation of a circular spinning work called “The Ultimate Painting,” which was done by the Drop City crew and later lost. Upstairs, Stell displays a set of prints that look like book pages, laying out Richert’s concepts of space from one dimension to ten. There’s also an interactive feature with Zometool components, which are used to make geometric solids with beams and spherical connectors. Stell pointed out to me how important these Zometools were in creating the shapes of Richert’s patterns, in particular the shadows they cast that align with shapes the artist uses.

The summer of 2019 is clearly Richert’s high season, and these stunning exhibits prove it.

Clark Richert in Hyperspace, through September 1 at MCA Denver, 1485 Delgany Street, 303-298-7554, mcadenver.org.

Clark Richert: Pattern and Dimensions, through September 15 at BMoCA, 1750 13th Street, Boulder, 303-443-2122, bmoca.org.