The Indigenous Nahua woman — who is also known as Doña Marina, Malinali and Malintzin — was enslaved by ruthless Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and became his cultural and linguistic translator as he destroyed the Aztec empire 500 years ago. Cortés also took Malinche as his mistress, and she had his son before marrying another Spaniard and having a daughter. She died around the age of thirty.

For some, Malinche’s story has been twisted into a romance between two races, à la Disney’s Pocahontas; she's seen as the mother of what became the European-Indigenous race of Mexico. But for others, her name has become a symbol for traitors who abandoned their people and culture, resulting in the pejorative term malinchista, or sellout.

Now the Denver Art Museum is offering a more honest look at the contested figure and clearing her name with Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche, which opened this month. With 68 works spanning five centuries, the exhibit provides visual examples of how Malinche’s image has shifted over the years. The show was organized by Victoria Lyall, the Jan and Frederick Mayer Curator of Art of the Ancient Americas for the DAM, and she says it's the first exhibition of its kind in the United States and even Mexico. Only recently has Malinche found sympathy for doing what she had to do to survive, Lyall explains. She wasn’t a traitor: During her short life, she witnessed the eradication of her culture while enduring personal trauma that has long been whitewashed by shortsighted narratives.

“The exhibition explores five concepts for which Malinche has served as metaphor: an interpreter, an Indigenous woman, a mother of mixed race, a traitor and, finally, the worst one — a slave,” Lyall says. “The organization of the exhibition explores these five metaphors in order to make visible the pervasiveness of these concepts and the many ways that these ideas shape our understanding of Malinche and her role in historical events.

“By extension, we also explore the impact of these very pernicious metaphors,” she continues. “One of the greatest moments for me is when one of our Mexican colleagues turned to me and said, ‘I will never use the word malinchista again.’”

To this day, “La Malinche” and malinchista are used to describe a perceived cultural traitor, says one of the exhibit’s featured artists, Sandy Rodriguez. She offers an example from July 2020, when Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva asked a female supervisor, who was calling into question the police department’s relationship with people of color, whether she was “trying to earn the title of La Malinche.”

“It’s usually one of the most derogatory things that one could call a woman,” Sandra Messinger Cypress, professor emerita of Latin American literature at the University of Maryland, told the Los Angeles Times.

Rodriguez created the stunning map that greets visitors when they walk into the exhibit. It's packed with symbolism that subverts its initial appearance as a traditional map of the route of Cortés, which has been reproduced throughout the centuries to document the Spanish invasion. This version follows Malinche’s life, from her birth to captivity to death, and is produced on a traditional paper, amate, that was used for books that the Spaniards outlawed and burned, Rodriguez notes. Some of those books explained the mystical and healing purposes of various plants, which Rodriguez has also drawn on the map in areas where they grow.

The symbolism doesn’t end there. Nineteen red hands represent the other women who were enslaved at the same time as Malinche or, as Cortés wrote to King Charles V, “given me as a present.”

“We don’t know the fate of these nineteen other women, so I placed [the hands] all across the border and in some parts of Mexico that were hot spots of trafficking in 2021,” Rodriguez explains. The sea is a Maya blue, a reference to Malinche’s ancestors, and the outline of Mexico is rendered in 24-carat gold to symbolize the “gold sickness” of the conquistadors.

“The opportunity to really think about a woman who was enslaved and trafficked brought me to the contemporary moment of being able to highlight the fact that our sisters, Indigenous women all across the United States of America, are continuing to suffer these types of abuses,” Rodriguez says.

The exhibit also offers a glimpse into Malinche’s life before Cortés, through Aztec sculptures from the 1500s. One is the water goddess Ghalchiutlicue, wearing a detailed gown and headdress with two braids down her back. Two others show how the clothing, hairstyles and even posture of Malinche’s Nahua people were gender-specific, with kneeling poses, large earrings, pulled-back hair and, most important, a huipil: a white rectangular tunic or blouse that was seen by the Nahua as a metaphor for the female body.

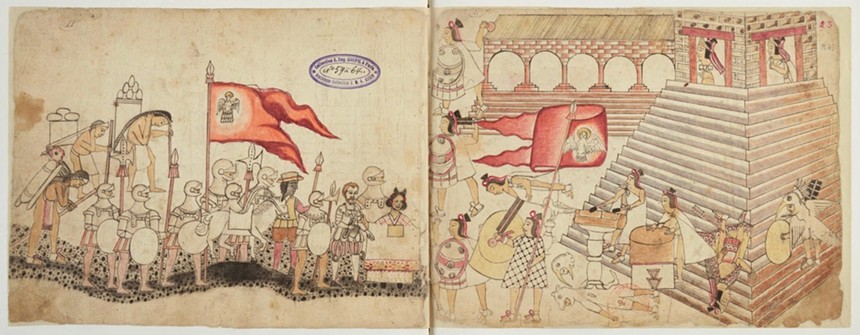

Malinche approaches Tenochtitlán with Cortés and the Spaniards, as shown in the sixteenth-century Codex Azcatitlán.

Courtesy Denver Art Museum

Lyall points out that Malinche is often reflected in a liminal space between the Indigenous and Spanish, with neither fully accepting her; sometimes she is placed between the two groups, showing her distance from both cultures, at others solidly with Cortés and the Spanish, with her Indigenous origins strongly emphasized by clothing and skin tone to separate her from the rest.

Malinche subsequently became a matriarchal symbol for the current Mexican race — a crossover between Spaniards and the Indigenous. This depiction has been the most contentious, leading Malinche to be both "revered and reviled," Lyall says. The exhibit includes paintings from the 1700s to the 1900s, done in different styles but showing Malinche and Cortés’s relationship much as the codices do: Malinche standing just behind the conqueror, with his arm sometimes crossing over her torso as if he is protecting her. Several oil paintings from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are painted in a European style, with her clothing and hair still reflecting Aztec roots but her skin prominently lightened, as she was viewed through a pro-European lens.

The twentieth century saw a renewed celebration of Mexico's Indigenous heritage, and Malinche was a prominent subject of calendars that hung as art in people's homes. "These printed materials really were responsible for disseminating mythologized aspects of Malinche, in which her style as an Indigenous woman was exaggerated and exoticized," Lyall says, pointing to a calendar painting in which Malinche is shown topless in an Indian headdress.

However, the shade of Malinche's skin becomes significantly lighter; in a popular 1941 poster by Jesùs Heiguera, a light-skinned Malinche is astride a horse with Cortés, who is in full armor. Malinche carries herself in a soft, romantic pose, her hand just grazing her heart — a far cry from the codices that showed her as more directive. The only Indigenous distinctions are found in her braided hair, sandals and embroidered dress.

"Jesus Heiguera would use very well-known actresses from the Golden Age of cinema, who were very, very white, to portray an Indigenous woman," Lyall explains. "Via these calendars, this image of her would cross the border."

In the most monumental portrait, a 1964 oil painting titled "La pareja (The couple)," Cortés is dressed in a full suit of armor, with a helmet shielding his face. Malinche is naked — with more authentic skin tones and her hair flowing down. To the side of each, a lion and an eagle represent the union of the European and Indigenous races with pervasive tropes.

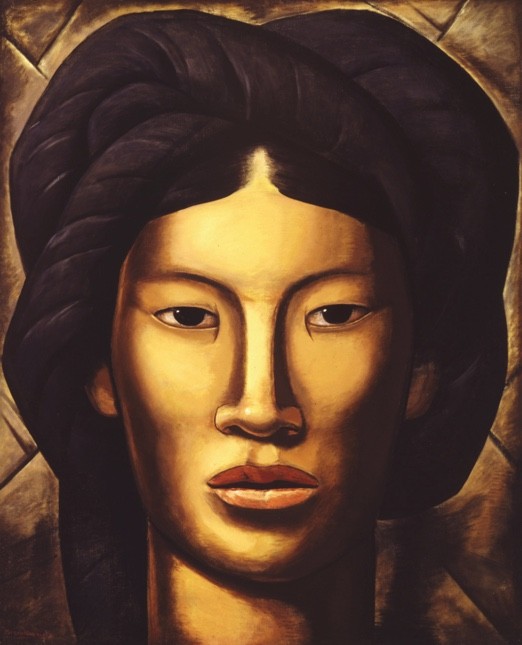

At the same time, some artists were creating more accurate portrayals. "La Malinche (Young Girl of Yalala, Oaxaca)," a 1940 painting by Alfredo Ramos Martínez, "shows Malinche with her hair wrapped in a style of Yalala, a community in Oaxaca," says Lyall. "But he gives her a monumentality and a beauty that really elevates her Indigeneity as something to aspire to."

In the ’90s, artists took yet another approach to Malinche, displaying a more authentic understanding of what she'd endured as an enslaved woman. The 1991 painting "Adam and Eva Double Exposed," by John M. Valadez, shows a Latina woman grimacing in the lap of a bald white man, who is clutching her with a vacant but cloying expression. A provocative and menacing movement is implied by the subjects being painted in tandem, looking almost like a foursome between two pairs of identical twins. In the background, the patterned wall holds a significant framed painting: Valadez has re-created José Clemente Orozco's 1926 mural "Cortés and Malinche," in which Cortés and Malinche pose naked, his arm crossed over her and his foot on a dead Aztec man. The detail blatantly calls the past into question, addressing how Malinche became a symbol for servile domesticity, and the effect is immediately disturbing.

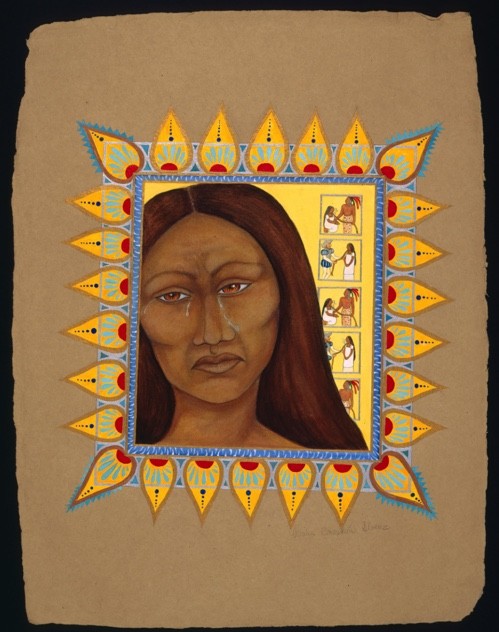

Malinche is portrayed perhaps most truthfully in a stunning image by Cecilia Alvarez from 1995, titled "La Malinche Had Her Reasons." In the background are five boxes, each showing Malinche with a rope around her neck, held interchangeably by a conquistador and an Aztec man. Malinche’s face is magnified in the foreground; tears roll down her cheeks as she looks away from the boxes that represent the trauma she endured from both the foreigners and her own people.

At the show’s exit, visitors are encouraged to leave a note that provides a biography of Malinche in six words. From what has already been submitted, it appears the show has had its intended effect, with one particularly poignant note offering this: "Rarely cherished, mostly used, almost forgotten."

Almost.

Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche runs through May 8 at the Denver Art Museum, 100 West 14th Avenue. Find out more at denverartmuseum.org.