They built projects that defied the law, capitalism and respectability. They created art that would be tough to hang in many of Denver’s commercial galleries, too many of which were peddling snooze-inducing Western landscapes and dusty abstractions, wallpaper for the rich. They presented music as noisy and gritty as the surrounding industrial area. They turned dreams — fueled by booze, drugs and idealism — into reality.

While the Denver Art Museum; the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, which was founded in 1996 and moved into its current building in 2007; RedLine Contemporary, founded in 2008; and commercial and co-op galleries were offering some programming to showcase and support local artists, Rhinoceropolis and adjacent venue Glob made room for experiments created without the restraints of professionalism. Over the years, the spaces housed creatives like the late Colin Ward, a prolific musician and visionary who has a posthumous exhibit at Meow Wolf’s new Denver installation Convergence Station; artist, musician and fashion designer Travis Egedy, who makes celebrated electronic music as Pictureplane and now lives in Brooklyn; Madeline Johnston, who performs ethereal, grief-ridden songs as Midwife and has continued to find national success after moving to New Mexico; and many more — many of whom are now gone.

Rhinoceropolis didn’t host galas or have a board of directors to keep it afloat. The culture was built by the people who lived and worked in the warehouse and was funded by whatever money came in from shows.

From the space’s early days, twenty-somethings — toting messenger bags loaded with home brew — would bike there from crowded Capitol Hill apartments and Baker punk houses for pay-what-you-can parties. Some of those nights would turn into bacchanalias; others would attract just a handful of art students, arms crossed, glaring cynically at whatever oddball performances were happening around them: avant-garde opera, folk punk or glitchy noise.

At Rhinoceropolis, anybody who had a radical vision and could put up with the chaos had a home where they could make art and share their work. Wild-eyed filmmakers projected experimental films too edgy for the Denver Film Society. DJs threw dance parties too queer for nearby gay club Tracks, which had opened its current iteration on Walnut Street in 2005 — an early harbinger of the development that would soon come. After gatherings, kids would climb up dilapidated buildings covered in graffiti and drink beers, basking in the smoggy emptiness, grateful to live in an affordable city with room for all sorts of rebellious expression.

The graffiti scene was booming at the time — but without much in the way of institutional and legal support offered in other rapidly gentrifying cities. Many of the stars of today’s celebrated street-art scene were running through industrial areas and railyards in the dead of night, painting tags and graffiti. Most weren’t courted by urban planners and developers. They risked arrest to make their marks. Profit from that art? Few could imagine it.

Denver already had a rich history of muralism, dating to the historic Chicano arts movement, which took off in the late ’60s and early ’70s, led by such artists as Carlota EspinoZa, Emanuel Martinez and Leo Tanguma. They designed their murals as permanent monuments to their community’s history, spirituality and role in Denver. But while their work was being memorialized nationally, Denver itself did little to preserve that art.

Instead, in the mid-2000s, graffiti and even some legacy murals were being buffed in the name of progress.

While some entrepreneurs were beginning to see how outdoor art could be turned into profit for developers, most viewed the pieces spray-painted on walls as blight, vandalism to be punished.

But Denver was already changing. In 2005, Tracy Weil and Jill Hadley Hooper, two artists with studios in old warehouses near the new Rhinoceropolis, founded the RiNo Art District — a very different sort of project, named for River North, the part of Five Points near the South Platte that the city announced in 2004 would be developed. The district, incorporated as a nonprofit, was business-minded, politically savvy and committed to turning the industrial area into an artful destination with plenty of amenities. Doing so would surely be a boon for artists already in the neighborhood, the founders thought, and also encourage more mainstream Denver businesses and organizations to think creatively.

A few years later, in 2009, the city’s cultural agency launched the Urban Arts Fund as a graffiti-prevention strategy that would pay for murals on public walls prone to being tagged and vandalized. The following year, longtime graffiti artist Robin Munro, aka Dread, started Crush Walls, a mural festival that brought permitted street art to the city, offering some funding to artists.

Developers began throwing money around the neighborhood. Soon it was clear that the RiNo Art District was becoming a major force in the future of Denver as tens of thousands of newcomers poured into the city and apartment buildings began to rise along Brighton Boulevard — many covered in city-sanctioned spray paint. Through it all, Rhinoceropolis and the RiNo Art District managed to cohabit peacefully.

The first real sign of trouble came from outside Denver: Five years ago this December, Oakland’s Ghost Ship warehouse went up in flames during an underground dance party; 36 people died. Days later, Denver safety inspectors began a crackdown on DIY arts spaces, evicting the artists living and working at Rhinoceropolis, Glob and other spots across the city.

In the wake of the Ghost Ship crackdowns, many who had been living and creating in old warehouses were suddenly out of a home and studio. Artists formed Amplify Arts and rallied for safe spaces and funding, dropping creative projects for dogged advocacy. The city responded in fits and starts, ultimately offering funding through the Safe Creative Space Program and Fund to bring many of those spots that officials had shuttered back to life.

And an even bigger influx of cash and energy was on the horizon: Meow Wolf, which had started a decade earlier as a ragtag collective in Santa Fe, had turned into the next big thing in immersive art, thanks largely to the vision of co-founder Vince Kadlubek and major support from Game of Thrones author George R.R. Martin, which had allowed the creation of House of Eternal Return in an old bowling alley. While that Santa Fe installation was collecting raves around the country, Meow Wolf dumped cash into Denver’s struggling underground scene. It also began exploring a much more ambitious project in the Mile High City: creating a second Meow Wolf installation. In early 2018, after property owners held a beauty pageant of possible spots for the massive facility, the lucky location was announced: a new building that would be constructed at the juncture of Interstate 25 and the Colfax viaduct.

While the future looked bright — at least for ventures with big dreams and bank accounts to match — DIY venues, mostly run by people who had no background in business, fundraising or city safety codes, were closed for months. Some were shuttered for over a year — like Glob, whose longtime lease holder, John Golter, learned the finer points of construction and working with zoning inspectors.

By the time Rhinoceropolis finally reopened in 2019, many DIY artists had already fled to cheaper cities. Denver’s co-op galleries, which had been such hallmarks of the city’s cultural scene in the ’80s and ’90s, had largely moved on to Lakewood. And while the RiNo Art District still billed itself as the place “where art is made,” development was the major thing happening in the area. Artists were no longer able to afford the place they were making so trendy.

Although there were plans for an artist housing project through national nonprofit Artspace in developer Westfield’s North Wynkoop neighborhood, where international concert promoter AEG was building its Mission Ballroom, the housing project disappeared in 2019, when the timeline for opening the music venue was pushed up and the nonprofit’s funding plans were scuttled.

"With Love From Denver," 2314 Broadway #100.

Pat Milbery, Pat McKinney, Jason Graves and Remington Robinson

The mural trend was a late-capitalist echo of Mayor Robert Speer’s City Beautiful movement of a century before, which had attempted to make ugly, industrial Denver a magnificent Queen City of the Plains — only this time, the boosters gussying up the city fetishized gentrified-hipster Brooklyn and San Francisco more than Beaux Arts classicism. City movers and shakers commissioned BIPOC artists to celebrate their cultures on the walls of the very communities where many working-class people of color were being priced out.

Muralism became the preferred aesthetic of the wave of newcomers moving to town. Other neighborhoods in the city, including the Art District on Santa Fe, Westwood and East Colfax, also started incorporating the art form — recognizing that murals not only defined a community, but might help attract businesses...and development.

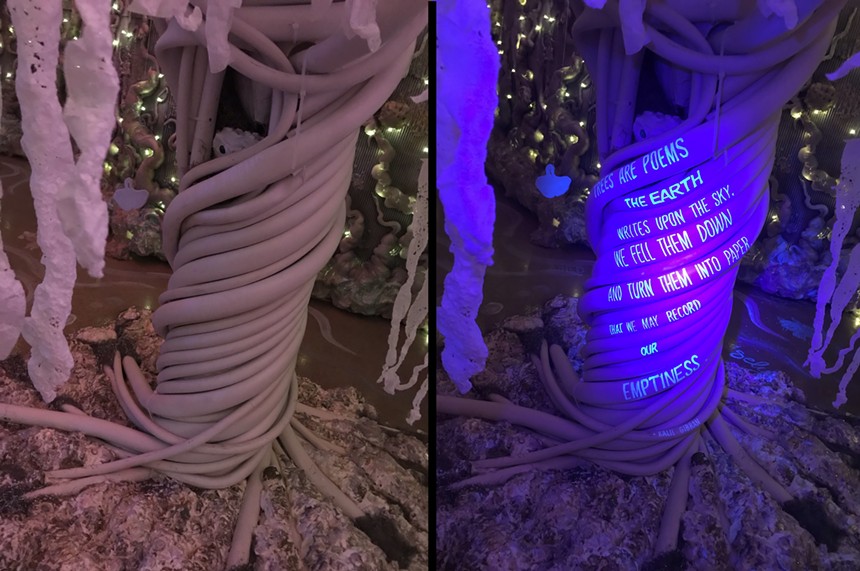

But murals were getting some competition from the so-called “immersive art” popularized by Meow Wolf. In 2019, the Museum of Outdoor Arts launched Natura Obscura, a thirty-artist, tech-rich Jungian installation designed by Prismajic. Marketers started using the words “immersive experience” to describe everything, including pop-ups in the culinary and nightlife scenes. The well-funded Denver Center for the Performing Arts Off-Center brought immersive productions like Sweet & Lucky, The Wild Party and mastermind Lonnie Hanzon’s Camp Christmas to life.

Meow Wolf itself launched Kaleidoscape, an artist-driven dark ride at Elitch Gardens with installations from Frankie Toan, Laleh Mehran, Kenzie Sitterud, Michael Ortiz, Chris Coleman, Brick Suede and Katie Caron — not that you’d know who was behind it from the ride.

But Meow Wolf’s ride was about to get wilder. In October, the company announced that longtime CEO Kadlubek had stepped down and would be replaced by corporate heavyweights: Chief Creative Officer Ali Rubinstein, coming from a 22-year career at Walt Disney Imagineering; Chief Financial Officer Carl Christensen, who had worked for Goldman Sachs, investmentbank.com and the Color Run race series; and Chief of Content Jim Ward, who had been president of Lucas Arts and senior vice president of Lucasfilm. And by then, Denver would no longer be the first Meow Wolf outpost to open; a Las Vegas project was moving faster, with others to follow in Phoenix and Washington, D.C.

As Meow Wolf’s ambitions grew, so did its legal bills. Former employees sued in New Mexico, claiming that the company was engaged in both discrimination and unfair practices. In late 2019, Meow Wolf Denver community outreach director Zoë Williams sued, claiming the corporation was discriminating against female and non-binary employees; Denver artist Mar Williams, who had been hired as a narrative illustrator for the Denver project, soon joined in. But the Denver case was quietly settled by the end of January 2020; in the meantime, hundreds of local artists were clamoring for commissions at the new facility, already going up in the shadow of I-25.

Colorado’s culture industry had become a big business rivaling the Rocky Mountains themselves as a reason to travel and even move to Denver. The city was becoming more cool than cowtown, if you believed national publications.

And then came COVID.

If the DIY crackdown of late 2016 felt like a cultural dumpster fire, now the entire creative economy was a blazing inferno.

In March 2020, venues across Colorado were ordered closed — and many shuttered for good. Many arts organizations moved their programming online; Meow Wolf pushed back its opening date. Artists and creatives, out of a job, were unsure how to pay rent. Denver was more expensive than ever, and cultural workers weren’t working.

Foundations such as Bonfils-Stanton, government agencies including Denver Arts & Venues and Colorado Creative Industries, and nonprofits like RedLine Contemporary Art stepped in to help, finding money to distribute to anxious artists and cultural groups unsure of their survival. While some squabbled over who was funded and who wasn’t, most were grateful for any relief.

Outside of a few community-minded spots like Hope Tank, which found ways to pay muralists, most businesses cut back their arts budgets — if they had budgets to begin with. But the murals kept coming.

During the summer of 2020, protests against the high-profile police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Elijah McClain and other Black people spread across the country. In Denver, out-of-work artists used their skills to protest violence against the BIPOC community. Murals of Floyd and McClain, including stunning pieces by Detour, spread through the city. Milbery, whose works had started appearing on high-end developments and even a Visit Denver project, joined rising artist Adri Norris in painting a massive rendering of the phrase “Black Lives Matter” on Lincoln Street below the State Capitol. Street artist Koko Bayer, the grandchild of modernist sculptor Herbert Bayer, wheat-pasted massive hearts around town with the words “Hope” and “Esperanza” in the center of them.

Photographer Juan Fuentes, who has chronicled life on the city’s west side, worked on a massive “Unity” mural for Westwood. There he wheat-pasted the faces of people from the neighborhood, celebrating the community in a hopeful gesture during a bleak time.

Art historian Lucha Martinez de Luna, Emanuel Martinez’s daughter and head of the Chicano/a Murals of Colorado Project, began seeing success in attempts to preserve the Chicano movement’s remaining murals. Denver City Council even voted to make La Alma Lincoln Park a historic cultural district, which will go far to protect works like “La Alma,” painted by Emanuel Martinez decades ago at the neighborhood’s rec center.

Social-realist photographer Armando Geneyro, who had spent the past few years chronicling Denver’s changing Chicano culture and other communities being displaced, turned his lens on the protests. His work has since been championed by the cultural establishment, with a major retrospective, Armando Geneyro: Brick and Soul, at the History Colorado Center.

With History Colorado leading the way, other cultural institutions that had long had mostly white boards began re-examining their practices as well as their past and upcoming projects, planning for more progressive programming — when programming returned.

In the meantime, groups like Wonderbound, Cleo Parker Robinson Dance, experimental film project Collective Misnomer, Lighthouse Writers Workshop, Buntport Theater and Denver Film pivoted toward online programming — keeping culture alive as well as they could.

During COVID, the word “pivot” replaced “immersive experience” as one of the most overused terms. Cultural institutions attempted to be nimble, but with their facilities dark, mass layoffs swept the sector.

Some innovative projects moved out of their usual homes and into the streets. Curator and artist Doug Kacena of K Contemporary teamed up with the Athena Project for #ArtFindsUs, mobile performances that took art outside. Rainbow Militia, the experimental circus troupe, launched Gnome Away From Home, a performance in a historic Berkeley house slated for demolition, among other productions.

And organized mural projects returned. In the summer of 2020, Alexandrea Pangburn, who was working for the RiNo Art District and collaborating with Crush Walls, launched a women and nonbinary mural festival dubbed Babe Walls to combat patriarchy in the street-art scene and provide an outlet for artists who were not getting equitable attention through Crush. She threw her first fest in Westminster; the 2021 edition took place along the Ralston Creek Trail in Arvada. Street art was spreading into the suburbs.

While Crush Walls returned in 2020 for a pandemic edition, shortly afterward, festival founder Munro faced sexual-assault allegations from prominent street artist Grow Love and other past romantic partners — all of which he denies. Amid the ensuing scandal, he parted ways with the RiNo Art District, whose capacity for contracting muralists was temporarily derailed by the implosion of Crush. (Munro retained the Arts & Culture Innovation Award that Hancock gave Crush Walls in 2017.) The District has since launched the RiNo Mural Program, a monthly series of street-art events correcting Crush Walls’ longstanding history of disproportionately showcasing white male artists.

Despite all these efforts, most creatives were largely out of paid work for months until the economy began to restabilize through emergency grants.

One exception was the local artists working on Meow Wolf Denver commissions. Although the collective-turned-massive-entertainment company had been forced to lay off employees, cancel planned installations in Phoenix and Washington, D.C., and temporarily close House of Eternal Return because of the pandemic, it had hired over a hundred Colorado creatives to contribute to the still-unnamed installation rising in Denver, all of whom had signed non-disclosure agreements to keep the work secret — and silence any potential criticism of the process.

By late spring 2021, as vaccines were shot into arms, the cultural scene reopened. Music venues such as Red Rocks Amphitheatre and Levitt Pavilion returned from a lengthy shutdown, and smaller indoor spots started preparing for live shows. Mayor Michael Hancock touted an All-Star Summer, as Major League Baseball’s All-Star Game made a quick move to Denver. The city also announced a re-energized concert series at Sculpture Park. Venues and galleries filled up again, and First Fridays came to life. The Denver Performing Arts Complex was reopening for the Colorado Ballet, the Colorado Symphony, Opera Colorado and, finally, DCPA theater productions. Denver Pride, the Cherry Creek Arts Festival, Taste of Colorado, the Underground Music Festival, the Westword Music Showcase and many other citywide festivals rebooted with new COVID considerations.

Even as the coronavirus morphed and the Delta variant took its toll, hope had returned — cautiously. Promoters Live Nation and AEG set the precedent for how to bring back in-person events safely, requiring proof of vaccination at concerts, and many other organizations followed suit.

Meow Wolf finally announced the opening date — September 17, 2021— and name of its Denver installation: Convergence Station. For its location, organizers had eschewed RiNo and other areas around Interstate 70 in favor of another industrial zone — but outside of the roar of interstate traffic, the area had been quiet for years. The land was connected to the history of the city, though, since these banks of the South Platte had been where the Arapaho and Cheyenne had camped before gold seekers started flooding in.

The city was ready for something big and new coming out of this bleak pandemic, and Meow Wolf Denver fit the bill.

The DIY Denver artists who collaborated on Convergence Station — this time working within government codes, as well as the rules of capitalism, as they fulfilled the vision of a multimillion-dollar corporation — had once again created a wild art destination in a run-down industrial zone. And as the public flocks there to explore the mysteries of the space, the area is getting ready for another big transformation.

Convergence Station’s maximalist sci-fi spectacle is almost enough to distract artists and the broader community from the next massive build coming to the South Platte River. Revesco Properties, which constructed the four-story building where Meow Wolf Denver has a twenty-year lease, is pushing its even more ambitious project: the River Mile, which the developer describes as “a mile-long social catalyst” that is projected to take 25 years to build. It will boast more high-density housing. More blocky buildings. More dining and entertainment options, including fly fishing. And even some art.

Artists who paved the way will surely be employed to decorate the River Mile with sculptures and murals, contributing to the historic placemaking that will transform the waterway where Denver was founded into yet another chapter of the City Beautiful, another attraction for boosters to tout, another sellable identity.

Will the art be as political as it was in the summer of 2020? Will it acknowledge the longstanding communities that made their home in the floodplains of the river, from the Indigenous people ousted so that the city could be built to the later waves of Jewish, Italian and Latino immigrants? Or if the official art is merely decorative, will artists remedy the historical erasure and force the new development to reconcile with its past through un-permitted graffiti?

Back in the RiNo Art District, situated among breweries, condos and a few remnants of the old industrial neighborhood,

is the new RiNo ArtPark. Filled with sculptures, gardens, massive swings, space for concerts and a soon-to-open branch of the Denver Public Library, the park also offers eight affordable studios run by RedLine Contemporary, providing workspace for artists including hope-heart purveyor Koko Bayer.

Not far away are the warehouses where Rhinoceropolis and Glob once dominated the city’s DIY scene. Beyond the sidewalks where scooters are zipping by, there’s a “For Rent” sign on the door of Rhinoceropolis.

Are the venues gone for good?

“I’m not doing shows at Glob due to the pandemic,” says Glob’s John Golter, who was instrumental in bringing both venues back from post-Ghost Ship closures. “It’s not the time, and we’ll see what happens this spring. I can afford to take a break and not have people gather.”

Is there hope that despite that ominous For Rent sign and almost complete redevelopment of Brighton Boulevard that the keys to these legendary spots will stay in the hands of the DIY arts community? That the experimental culture that once thrived there might not be entirely priced out of Denver?

“Of course,” says Golter. “It’s not as if I ever gave up.”