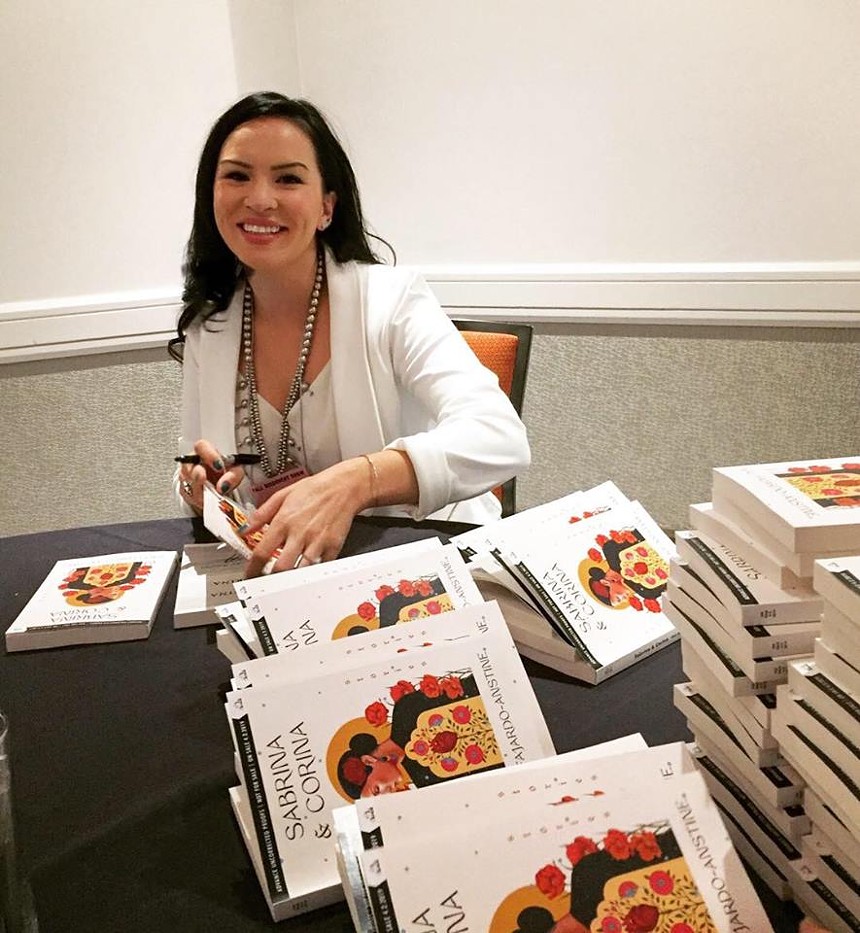

Kali Fajardo-Anstine lives and breathes Denver. That's clear in her breakthrough collection of short stories, Sabrina & Corina, released by One World Random House on April 2. So it makes sense that she’s launching the book at Lighthouse Writers Workshop, where her writing career began, in the city to which so much is owed by the collection and its characters. Sabrina & Corina, like Fajardo-Anstine herself, is utterly homegrown.

In advance of that launch party on Friday, April 5, we spoke with Fajardo-Anstine about her work, the role that family and place play in her writing, and how she experiences the Denver of the past and of today.

Westword: Your first short-story collection, Sabrina & Corina, is debuting at Lighthouse Writers Workshop. You've been associated with Lighthouse for quite a while; what does it feel like to be able to celebrate the launch of your book there?

Kali Fajardo-Anstine: I began taking classes at Lighthouse when I was nineteen or twenty. I had seen fliers for their events and classes while working at West Side Books in north Denver, and I wasn’t sure the space was for me, but I desperately wanted to learn to be a better writer. I asked my father for a class for my birthday present that year, and he agreed, helping me sign up for "Intro to Novel Writing" with longtime Lighthouse instructor Rebecca Berg. It was a wonderful time for me as a young writer. I’d get dropped off by my father at the old Thomas Hornsby Ferril House, and for a couple hours once a week, I’d learn from writers who came from all walks of life. Years later, after earning my MFA, teaching and living throughout the country and publishing some of my stories, I returned to Denver in 2017 and knocked on Lighthouse’s door. I ran into Dan Manzanares and handed him my CV. I wanted to teach there. I wanted to come full circle, and Lighthouse heeded my request.

To be able to hold my launch at Lighthouse, where so much of my writing career started, is a gift. In my life, I make sure to pay tribute to origins and beginnings, whether that is my ancestors or my personal beginnings, and to hold my launch at Lighthouse feels like a way to pay homage to the young writer I was and the author I am becoming.

The book is something of a love song to local Chicana culture. How personal is that for you, your family, your own history? How much of you is there on the page in this collection?

I think the book is a love song to Denver as I know it, a multicultural space, a convergence zone where the various cultures that made me came together in a unique blend. My ancestors migrated north from southern Colorado in the 1920s and 1930s. They came to Denver for a better life, for work, and for their dreams of owning property. Many of our family homes in Denver are gone now due to gentrification and the financial and psychic stresses it causes a displaced people. I come from an enormous Wild West Chicano family, a family that is mixed with Filipino, Jewish and Anglo. Our mixture and existence comes out of our place. I put all of myself on the page, for my characters, major and minor, are birthed in my heart and mind. They have echoes of my family, my five sisters and brother, my great-grandmother, my great-aunties, my grandfather and all the elders.

You come from a storytelling tradition in your family. Can you relate what your mom (Renee Fajardo) does with her storytelling, and how that inspired you? How much of your voice do you owe to your mom?

I used to be embarrassed of my mother’s storytelling. She’s expressive and lively. She dresses up in traditional clothing. She speaks in voices and projects her words into the crowd with the self-assurance of an actress. It was only later, after I had started doing readings and developing my own voice, that I realized in many ways my obsessions and intellectual interests mirror my mother's, but instead of the oral form, I utilize literature. I suppose I owe everything to my mother, in the same way that all children owe their existence to their parents.

Funny story: When I was in second grade, my mother helped me make a diorama of the Sand Creek Massacre in oil pastel. The scene was my idea, but I knew about the Sand Creek Massacre because my mother had explained the injustices of our place very early. She made sure that her children were aware of their world, in all its ugliness and beauty. My second-grade teacher called my mother to complain about the diorama, but I remember my parents expressing pride rather than shame.

Do you consider these stories feminist? How do you hope they address the rising voices of women in modern America?

Yes, my work is feminist, if you believe that women’s voices need to be heard and not relegated to a marginalized alley of literature. In the Atlantic in 2001, Alice Munro said this when asked if she considers her work feminist: “I think I'm a feminist as far as thinking that the experience of women is important.” I agree with that, but I am not a theorist and I am not an academic who studies these concepts. I’ve studied storytelling and literature and the realities of human life around me. Women are dominant in my reality, and it never occurred to me that I was writing “women’s literature.” I am writing out of my heart and my mind and worldview, which is a deeply female perspective.

You've spoken passionately in the past in defense of the short story. In this modern-day literary market, short fiction often gets a reductive reputation in terms of audience appeal. How do you think we keep the spirit of the short form alive, as writers?

I think MFA programs, where the writing of short stories is encouraged due to the time constraints of workshops, will keep the form alive out of matters of practicality. But I also don’t think the form is in any danger of disappearing. Look at all these genius short-story writers publishing today! Alice Munro, Joy Williams, Edward P. Jones, Ann Beattie, and the list goes on and on. The market changes, and story collections go in and out of style like anything else. Each story, each tale, teaches us how to write it — and sometimes we need a larger canvas like a novel, other times we need a poem or an essay, and often, for me, I need a short story.

What other Colorado authors inspire you? What in their work do you admire?

There are many! I love, love the work of Kent Haruf. I blew through Plainsong and Our Souls at Night in a couple weeks back in 2017. I immediately went online to research him some more, in order to write a letter to Haruf expressing my delight over his prose, his harsh yet beautiful worldview, and the world he created in Holt. I was heartbroken when I saw he had passed away in 2014.

I am also deeply influenced by Katherine Anne Porter, and not many people know that her novella Pale Horse, Pale Rider is set in Denver during the influenza pandemic. And I loved Pam Houston’s latest, Deep Creek, about her ranch in Creede. I like to see our region represented, and I deeply want there to be a large body of place-based literature out of Colorado, but I also want it to reflect our diversity, and more writers of color and indigenous voices are needed. I am so glad that I’ve found amazingly talented writers like Manuel Ramos, Steven Dunn, Erika T. Wurth and others who are providing Colorado with a more rounded representation of our collective experience.

You grew up in Denver. How does the city play into your creative process? There are lots of references in the book to the North Side, but then there's a Cheesman Park story, too. What part of town did you call home? Where in town do you find spaces to write?

When I was in graduate school at the University of Wyoming, a lot of my peers were writing about the American West, and I found this interesting, as many of them weren’t originally from this space. I thought long and hard about what I had to offer the world of literature. I wanted to understand what made my voice unique. That’s when I began to realize that my work was unique because of my place and all the things my people had experienced there for generations. I’ve lived and worked in different parts of the city. During my undergraduate years at Metro, I lived off Ninth and Inca (and was a couple blocks away from my auntie and godmother on Galapago). I also lived off Twelfth and Colorado, and most recently I lived in a low-income housing unit behind Coors Field. I know this city the way I know my favorite books, line by line. Even when I go away, I can imagine the pulse and beat of Denver, this place that I’ve known since my first day of life. But there is so much now that I am excluded from in the city. I’ve never actually been inside of one of these high-rise glass apartments. I don’t know those people, though I have been curious about their lives and jobs, where they come from, and if they notice those of us down below who have always been here.

With that said, there are still pockets of the city where I feel at home. I love visiting the Western History floor of the Denver Public Library, where the archivists and librarians welcome me with open arms. In fact, DPL librarian Brian Trembath loves telling the story of how he went to high school with one of my uncles. I love writing at St. Mark’s on 17th, and I have written there off and on for years. And I love being at the Chicano Humanities and Arts Council, even in the new location off Second and Santa Fe.

Do you have a favorite memory about Denver? Where did you love to go as a kid? Is it still there? And what's the thing or place you miss most about the Denver of the past? What's been lost?

My favorite memories are within the homes of my elders, those homes we no longer can visit. Sometimes when I drive past the old houses, a sense of grieving and loss washes over me. I avoid driving down Galapago Street and Tremont Place on bad days, because I don’t want to feel so sad at the loss of community and the destruction of the historic heart of our neighborhoods. And I also love remembering visiting places like Monkey Mania and Rhinoceropolis, all the old warehouses where kids piled together and watched and supported bands from different parts of the country and the community here in Denver.

But the Denver of my childhood looms large in my mind, as well. The Capitol Hill where I lived as a baby. My mother used to push me in my stroller into Cricket on the Hill, and I remember the bartender — I believe his name was Pauly — would make me chocolate milks, fresh to order.

I don’t think we can quantify all that has been lost, for much of it no longer exists anywhere except in the recesses of fading memories. It’s a type of mourning I live with every day.

You’ve mentioned gentrification — one of Denver’s great challenges, as it deals with the issues of expansion and growth. It’s an emotionally charged issue for many; what do you think can be done? There seems to be this sense of helplessness surrounding the issue, especially for communities and families that were — or are — being displaced. But for allies, too. So what can Denver do?

I think this is an excellent question, and I would also like to know the answer, because, frankly, I don’t know. I’ve spent my adolescence and twenties experiencing the gentrification of Denver in real time, hardly able to process and intellectualize what my community is facing. In terms of what can be done, I think those questions should fall on those actively gentrifying spaces rather than those of us who have been displaced.

So I turn this question to those coming from the outside: Are you comfortable living in and taking over a historically Latino neighborhood? Do you know the history of Five Points? What can you tell me about the nations who were here before Anglos? And do you find it acceptable that artists and teachers cannot afford to live in proper housing in Denver?

All good questions. Do you think some transplants come into it blind? Someone from another state buys a house they like in a neighborhood to which they're drawn, and they have very little access to the history that they may be displacing. What's the responsibility there — and with whom does it ultimately lie?

I've lived in Key West, Florida; Spartanburg, South Carolina; Laramie, Wyoming; San Diego, California; Durango, Colorado, and elsewhere. I can tell you about the history and lives of people in each one of those places, because I asked and researched while living there. I was raised to care about tradition and histories and levels of power. But I also learned about my new places out of safety. I need to know the people whom I live around. I need to know as a woman of color what I am encountering in the world. I think it's a rather startling form of privilege to believe you can move into a new space completely blind, as you say.

So what role can art and literature play in the preservation of these lost spaces and communities?

To create art is to say that your voice and vision matters. It’s a statement that says, I am going to make something unified where only pieces existed before. Sometimes when I envision the artist, I imagine a gatherer, an old woman piling sticks together in a bundle, carting her objects away and using them to build a house — a nearly everlasting structure, for all things eventually disappear. But what art can do is deliver news to the world from the perspective of a single creator. If you’re lucky, your work will receive a wide audience, and you can show that audience where you have been and what you have seen. Art can preserve these lost spaces because genius art is hard to deny and hard to un-see. In some ways, I wrote Sabrina & Corina because I wanted locals and outsiders alike to know about the injustices of our place. I wanted people from far away, and even those right here, to read my stories and say, my God, I had no idea, but now I do. Or maybe they knew all along, and my work simply reinforces what so many of us experience on a daily basis.

What's the thing that symbolizes Denver to you — that thing you take with you no matter where in the world you go, no matter how the city changes?

The confluence of the South Platte River and Cherry Creek with the bluish mountains nestled in back. When I need to picture an origin, the place where it all began, I see that space, gushing and moving, more permanent than any of our lives.

Kali Fajardo-Anstine will read from her collection of short stories, Sabrina & Corina, at 6:30 p.m. Friday, April 5, at Lighthouse Writers Workshop, 1515 Race Street; the reading will be followed by a Q & A with Steven Dunn. Find out more at lighthousewritersworkshop.com.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "leaderboardInlineContent",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "tower",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

}

]