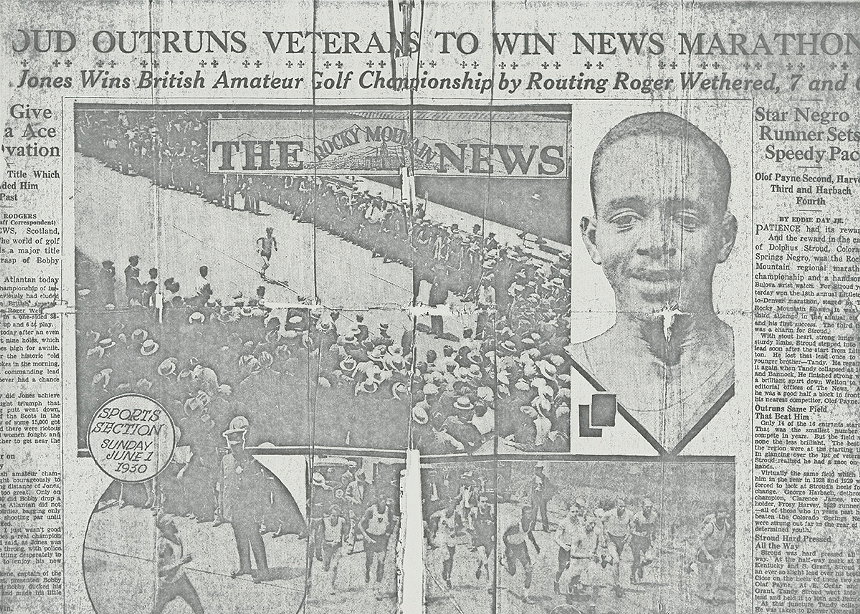

Stroud, who went by Dolphus, was aiming to reach the 1928 Olympics, an attempt he made eight years before the celebrated Berlin Olympics performance of fellow running pioneer Jesse Owens. He was drawn to the solitary comforts of competitive running during high school after being denied a spot on the football team because of his race, a common experience for African-American athletes in the segregated 1920s. Pikes Peak became his training ground and his escape; it was where he set a round-trip climbing record in March 1928, breaking one that had been held for 25 years, with a time of three hours and ten minutes. He then went on to win the 5,000-meter run at the Rocky Mountain Olympic Track and Field tryouts in June, which granted him entry to the Olympic trials held in Boston that summer.

While the tryouts' organizers had promised the winner transportation expenses for the Boston trip, that offer was rescinded when a Black athlete came out on top. Dismayed but undeterred, Stroud decided that he would still attempt to reach Boston by the one mode of transportation he knew he could definitely rely on: his feet.

Through a combination of walking, running and hitching rides by buggy and car (which were still relatively rare), Stroud traveled 1,765 miles in twelve days, successfully reaching the trials six hours before the first race. It was a death-defying trip that pitted an unforgiving schedule and the summertime heat against Stroud's physical and mental endurance, taking him to the very limit of his capabilities. Running to Harvard details this incredible journey and its aftermath against the backdrop of Stroud's large, equally groundbreaking family.

The film's executive producer and creative engine is none other than Stroud's great-nephew, Frank Shines. Shines has been waiting years to tell Stroud's story, and he's assembled an experienced creative team from the Springs area to help him do so: Executive director Ralph Giordano has been producing film and video independently and has been active in film preservation there since the late ’80s; Mike Pach, the assistant director on the project, is a photographer, author, teacher and the founder of the Colorado Photography Learning Group; and cinematographer Ky Hanchette is a longtime local director of photography who has worked for clients ranging from Space Force to the PGA.

For Shines, who currently resides in Tampa, one of the twists in telling this particular story is that for many years, he wasn't even aware of it. The Stroud clan is deeply rooted and widespread, even by American standards, and Shines's branch (his grandfather was Stroud's brother Tandy) was first extended to Oakland, California, then fractured. As a consequence, he grew up in the Bay Area without learning about his Colorado connections until he came here as a cadet at the Air Force Academy in the late 1980s.

"I knew nothing about the family until I got to the Air Force Academy," he says. That was when he received a phone call from a stranger who claimed to know him. Perplexed, he assumed it was a wrong number, but the caller insisted: "No, I know you. Don't you know the history of your family in this city?" Shines was unconvinced and about to hang up when she rattled off the names of his mother and grandfather, Vanessa and Tandy Stroud. "And I said, 'Oh, my God, okay, so who are you?'" Shines recalls. "She goes: 'I'm Lulu.'"

"Lulu" was Lu Lu Stroud Pollard, Dolphus Stroud's younger sister, the eighth of eleven children total, and a significant trailblazer in her own right. Gifted in finance, she became the first Black employee of the Civilian Office of Personnel at Fort Carson, then rose to become head of the entire accounting department there, among other supervisory roles. Once she retired, Pollard returned to Colorado Springs and, upon finding a dearth of information about African-American Coloradans, decided to collect some. Together with her second husband and some friends, she formed her own historical society dedicated to preserving stories, artifacts and photographs documenting Black history. Their invaluable preservation work became a foundation for later local collections, including that of the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum. Shines couldn't have been cold-called by a better family mentor, and in time, he even stepped into her shoes.

"My avocation is [being] the family historian," he says. "I'm trying to get as much of this information put into different types of media that will last and tell the story. Because otherwise, the kids just won't know. It will disappear fifty years from now."

Since graduating from the Air Force Academy, Shines has cultivated a diverse background that is well suited for the job of film producer, a role that requires a little bit of everything. Besides his time spent as a pilot, he's been an industrial engineer, a management consultant for such firms as IBM, a filmmaker, an author and a speaker; he also founded his own mentorship program, the Stroud Leadership Academy. Running to Harvard is just one version of Stroud's story that Shines is producing this year. He's also developing it as an opera with the International Brazilian Opera Company.

A key theme of both the cross-country adventure and Shines's own life is familial dialogue that carries victories and stories through generations. This connection is not just an oral history, but a sharing of strength, which he illustrates with a telling anecdote from Stroud's story. The athlete was just outside of Ohio, and "at that point, he ran the calculations, he's working out the math and the distance, and he's not there yet, and I can't remember how many days there were left, but he said: 'There's no way I'm gonna make it,'" Shines recounts. "A storm came, he huddled up underneath some tombstone in a cemetery, and he was ready to turn back that night. And he had some hard conversations with the images of the Stroud family past, so to speak."

There was already ample Stroud family history to invoke 96 years ago, starting with the young runner's parents. Stroud's father, KD Stroud, had been born free in 1870 on a Texas plantation, but his family tree included enslaved people from Ghana, the Tawakoni of the southern plains and the English/Irish owners of the plantation. His wife, Lulu Magee, was a woman of the Creek Nation whose family had narrowly survived the Trail of Tears. They met in the Oklahoma Territory, where KD helped to build — as well as attended and graduated from — Langston University, and later became a minister and studied law.

Thinking of their children's future, the pair moved to Colorado when statehood (and Jim Crow) arrived in Oklahoma. Once there, however, KD was unable to continue working in law and was forced take a job shoveling coal seven days a week, but he still brought home a newspaper every night to read with his children before going over their homework. With mentors such as these, it's easy to imagine the conversations Stroud had with the "family past" during that long night in the cemetery. The next day, he decided to push on. Soon after, he managed to snag a ride that took him the rest of the way, in part because a newswire story of his trip had begun to circulate. He made it to the Boston trials just in time, but his herculean effort had taken its toll.

"He said by the time he ultimately got there, his feet were just so swollen, he put on his shoes and he could hardly move," says Shines. With his body on its last legs and only hours remaining before he had to compete, Stroud knew he had to stay awake at all costs. Scared to sit for long lest he drift into much-needed sleep, he wandered the campus and visited the library at Harvard, where he hoped he would eventually study if he was successful at the upcoming games. He checked in for that morning's race and was given a red, white and blue uniform to run in, which "was a real source of pride," Shines says. As the event neared, Stroud stretched and began to warm up, still fighting off exhaustion.

"He said that he could hardly keep his eyes open at the start of the race," Shines says. Stroud recalled his previous victories and his many summits at Pikes Peak and tried to tell himself, "I'll make it, I'll be fine." But a limit had finally been reached. "When the gun went off, he ran and his feet just wouldn't move," Shines says. "He felt like he was shuffling...and it didn't take long before people were just passing him up. He made six laps and collapsed on the sixth lap."

It was a bitter disappointment for the young athlete. "He felt he let everybody down," Shines says. "That was his comment in his notes [and] in his journal." Stroud spent the summer recovering and working in Boston, after receiving a recommendation at the YMCA from a fellow leading runner, Joie Ray, who had witnessed the disastrous race. During this time, however, he also developed a new personal philosophy. "There's a phrase he used to always use: 'Obstacles are

"He said that he could hardly keep his eyes open at the start of the race," Shines says. Stroud recalled his previous victories and his many summits at Pikes Peak and tried to tell himself, "I'll make it, I'll be fine." But a limit had finally been reached. "When the gun went off, he ran and his feet just wouldn't move," Shines says. "He felt like he was shuffling...and it didn't take long before people were just passing him up. He made six laps and collapsed on the sixth lap."

It was a bitter disappointment for the young athlete. "He felt he let everybody down," Shines says. "That was his comment in his notes [and] in his journal." Stroud spent the summer recovering and working in Boston, after receiving a recommendation at the YMCA from a fellow leading runner, Joie Ray, who had witnessed the disastrous race. During this time, however, he also developed a new personal philosophy. "There's a phrase he used to always use: 'Obstacles are

stepping stones,'" Shines says. "And that's the way he thought about it from that point forward."

Stroud put that mantra to good use in the decades to come, and his further accomplishments could easily be the subject of another full-length documentary. He graduated from Colorado College and became a professor, a dramaturge, a historian and even the manager of a professional baseball team, the Black Giants. Toward the end of his long life, he traveled the United States for speaking engagements.

Shines's film is pushing toward the home stretch of its journey as well. He's hoping to premiere it next fall in Colorado Springs, but he and his team still have much to do, including filming with the young actor portraying Stroud in the portions of the film that are dramatic re-creations. A GoFundMe campaign is part of a larger fundraising push targeting both public and private donors, and contributors will receive "an insider's view, exclusive pre-release footage access, unseen historical family photographs and insight into ancestral research and filmmaking process." Stroud put that mantra to good use in the decades to come, and his further accomplishments could easily be the subject of another full-length documentary. He graduated from Colorado College and became a professor, a dramaturge, a historian and even the manager of a professional baseball team, the Black Giants. Toward the end of his long life, he traveled the United States for speaking engagements.

Participants will be contributing to the costs of research, filming and post-production. In addition, they'll have helped unearth the story of a Colorado pioneer whose recognition is long overdue. To the end of his life, Stroud stated that he had always intended for his efforts to give inspiration to both his Front Range neighbors and people like him everywhere who are striving toward goals and dreams.

"He said that he did it for the family, for the Rocky Mountain region and for people of color around the world," Shines concludes. "That's why he ran."

Running to Harvard is accepting contributions at gofundme.com. Find out more about Kelley Dolphus Stroud and the Stroud family at stroudfamilycolorado.com.