It was 1967, and Havu had dropped out of American University so that he could concentrate on his rock band, the Natty Bumppo. "There were also protests going on all the time, so it was very difficult to find a class with anybody in it, or anybody teaching it," Havu recalls.

The Natty Bumppo, for which Havu played drums and bass, was the house band at the newly minted Ambassador Theater. The venue, which neighbors perceived as a menace before it even opened thanks to announcements that it had booked such bands as the Dead and the Doors, would close by January 1968, but not before Hendrix's legendary five-night run.

Hendrix had just left a tour with the Monkees, the ’60s pop-rock band created for a TV show of the same name, after playing only six shows. When Hendrix's manager called the Ambassador, the venue booked the band for five nights, from a Wednesday to a Sunday, with the Natty Bumppo opening. "On Wednesday there were maybe twenty people, and by that Friday, there was a line around the block," Havu remembers. Word was spreading fast: The first three shows were $1.50, but ticket prices were raised to $2.50 the last two nights. That extra dollar was worth it: The final set ended with Hendrix burning his Fender Stratocaster and throwing it to the crowd. "There's a Facebook group for people who went to the Ambassador, and one person claims to have a piece of the guitar's neck," Havu says.

Hendrix would go on to achieve worldwide fame; for a while, it seemed as though the Natty Bumppo was on the same path. "We were a pretty big deal in D.C. in ’67," Havu reminisces. "We were part rock, part folk. There were anywhere from four to seven of us at any given time, depending on additional musicians that we needed. We wrote our own material; we didn't cover anybody. We had a couple of songs that got pretty popular on the East Coast."

The band was set to make its big break...and then Dionne Warwick got in the way. "The big blow was our manager at the time for Mercury bought the rights to the theme song for Valley of the Dolls, and so we recorded a version of that with a fourteen-piece backup orchestra that was pretty elaborate," Havu explains. "And Dionne Warwick, much to our chagrin later, had also gotten the rights. Our manager delayed the release of our single because the movie was going to be delayed, and he wanted it to coordinate with the release of the movie. Well, Dionne didn't wait."

Not long after she stole the band's thunder, the members of Natty Bumppo parted ways; Havu moved to San Francisco to join a seven-piece chamber-rock orchestra that also simmered out. But he still looks back on those days fondly. "It was heady times. It was a lot of alcohol and a lot of drugs," he says with a chuckle.

Wearing a crisp button-down and khaki shorts, today Havu cuts the perfect figure of a fine-arts gallerist, and he'll be celebrating his long career with his gallery's upcoming show, From All Angles: Fifty Years in the Art Business. He got his start in the art world after he moved to Aspen in 1968, but not immediately. Back then, Havu was still running on freewheeling momentum and wanderlust; his beginnings in the Rocky Mountains were anything but art-world glamorous.

"There had been a guy who was kind of a groupie of Natty Bumppo who had a landscaping business and a small tree nursery, and I started working for him when I came back," Havu says, recalling his return to D.C. from San Francisco. "And he said, 'Let's go to Aspen.' He had been a ski patrolman at the Aspen Highlands in 1964. And I said, 'Sure, fine.' I didn't know anything about Aspen. So we jumped in his pickup truck and drove out to Aspen and lived in the explosives cabin of the Ajax Mine in old Snowmass."

They had no money, so camping out in the abandoned mine seemed like the best option. The owners eventually noticed, and Havu recalls that they said he and his friend could stay there if they kept an eye on the place. So the two lived as mountain men, gathering fresh water from a nearby spring (where they would also bathe) and eating fish they'd catch.

"Then the winter was pretty brutal. We made it through...and then we had no money, we had no food," Havu says. He moved to town and held a variety of odd jobs that also provided housing, painting the newly renovated St. Moritz and then working as a busboy at the Red Onion, where he lived above the kitchen. In 1970, he moved to Telluride, where he worked on a ranch, caring for cattle and plowing fields, before returning to Aspen six months later.

While painting houses and working as a server in 1973, Havu discovered that a frame shop was closing. He used his savings to buy all the framing equipment and found a small space to open his own shop. Not long after, he moved to a new Aspen location, where he debuted his first showroom, the William Havu Gallery, alongside his framing business. He also got a side gig selling prints for HMK Fine Art, which was the largest printing company in the U.S.

"They would contract artists to do editions of etchings, lithographs and engravings, a few silks. I started doing that, and it began to be pretty profitable. So I hired somebody to run the gallery while I was on the road selling prints to galleries," Havu recalls.

He sold his gallery in 1979 to commit to HMK full-time, and moved to Evergreen. Through his work as a salesman, he learned about art history, selling authentic fine-art prints by the likes of Joan Miró and Jacob Lawrence. When HMK folded (the owner was having tax issues), Havu and his friends decided to start their own print publishing company in Denver called Art Group Partners. He was well aware of scandals surrounding fake prints, with several artists in the ’70s such as Salvador Dalí discovering that they could make buckets of money by just signing a paper and sending it to the print publishers, who would handle the rest. "There's always been a lot of deception in the art business, because it's totally unregulated, but that was the height of scandalous behavior," Havu explains. So he focused on monoprints, which are only made once.

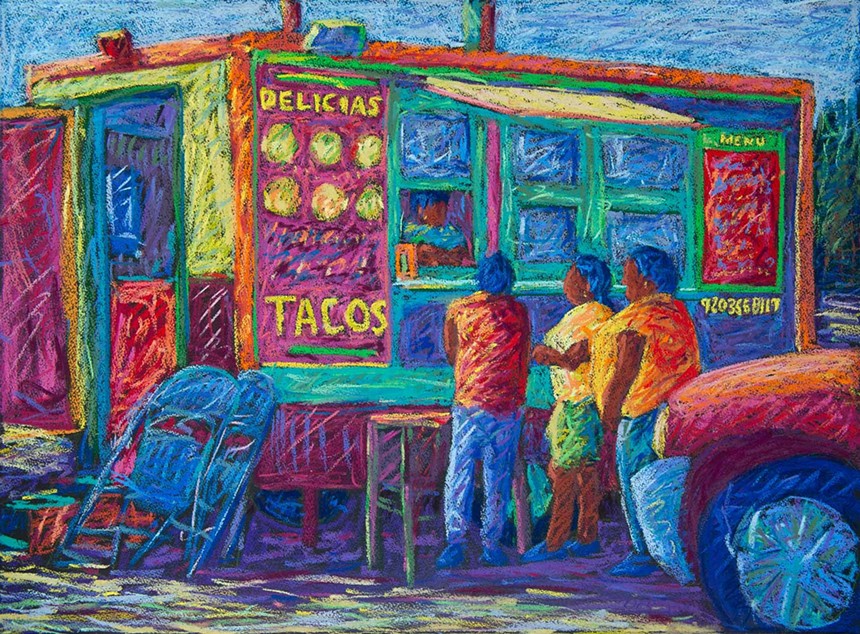

The Art Group Partners office was above the first Robischon Gallery, at East 17th Street and Park Avenue; both operations opened on the same day in 1981. For the monoprints, Havu connected with Denver artists such as Tony Ortega, Emilio Lobato, Sandra Kaplan, Michael Brangoccio and more, many of whom he has been working with ever since.

The "traveling salesman era" of selling prints soon ended, Havu says, "because there were more artists and more places where good art was being made. It wasn't necessary to get art from New York, from Paris." While Art Group Partners fizzled in ’83, Havu was only gaining momentum. He kept adding artists to his roster and opened another showroom in 1985 at 26th Street and Brighton Boulevard, which he called William Havu Fine Art.

"And then LoDo started happening," Havu says. "Jim [Robischon] moved and built his gallery at Wazee Street in ’90, and a space came up there. I took that space in late ’90 and opened in ’91."

The area became a popular place for art, with Havu's spot (which he called 1/1, or "one over one"), Robischon, Sandy Carson's gallery, the late Robin Rule's first gallery and the Center for the Visual Arts. "We got a permit to close the street on First Fridays, and we'd have 2,000 people," Havu remembers. "That lasted for a while until the stadium proposal was accepted for Coors Field...and then all the rents started going up astronomically."

When Havu's lease came up for renewal in 1998, his landlord had quadrupled the price. "It was obvious I wasn't able to stay there," he says. "I was riding around on my bicycle here in the Golden Triangle...and they were just starting to build this building. I went out and looked at the blueprints, and they said, 'Well, this space is going to be 3,000 square feet. We're making it as a gallery and hoping a gallery moves in here.'" It was meant to be. William Havu Gallery opened on Cherokee Street in 1998, where it's remained for the past 25 years. Havu officially evolved from an itinerant rocker without any arts degree to a bona fide curator with a successful gallery, who could talk about art all day long. Unlike other curators, Havu never sticks to one genre or style — he instinctively knows what's good, adding clout to Denver's art scene by promoting the work of not just local innovators, but creatives from all over the states, including the renowned Sam Scott. "That got the ball rolling, when I started working with Sam, because he's a big name and people respect that," Havu says. "So I was able to attract some pretty serious people."

As he looks forward to his upcoming show, which opens on September 8, Havu is also looking back on decades of art history. Sixty-eight artists are connected to his gallery; he'll display works from at least fifty of them, so curating From All Angles has been laborious. "I'm still trying to figure out who and what to put on the walls, because it's covering six decades: ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, 2000, 2010, the brief period of the 2020s," Havu says. "I'm trying to base it on who's been really seminal over a long period of time."

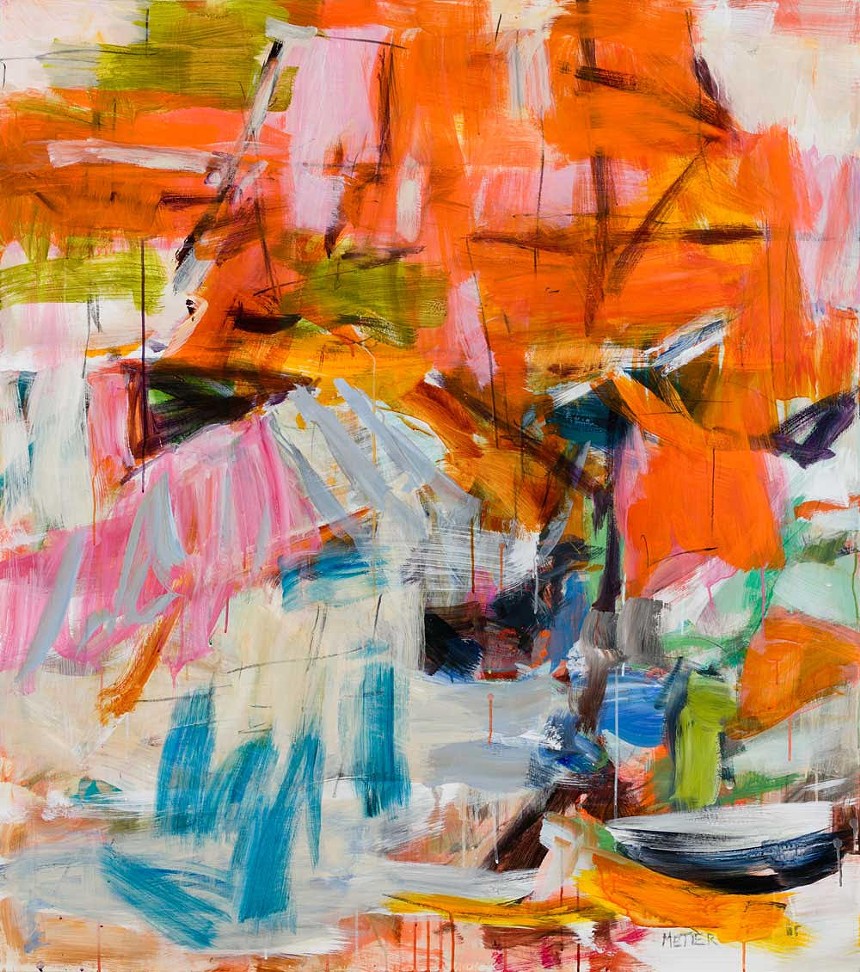

He's already chosen paintings by Ortega, as well as works by Sushe Felix, Jeanette Pasin Sloan, Dennis Lee Mitchell, Amy Metier and more. One of the most exciting inclusions is a self-portrait by Kurt Vonnegut from 1995, as well as a portrait by Ralph Steadman, whose unique style is instantly recognizable thanks to his illustrations for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. "This is going to be a last-minute curatorial nightmare," Havu admits, laughing. But as he shuffles through all the beautiful paintings he has to choose from on his computer, from abstract expressionism to photo-realist landscapes, it's easy to see that this is his passion.

"I have found that the longer I’m in this business, the more people seem to value my opinion on art, though I wish they’d ask me more often," Havu reflects. "Another highlight would be the fact that for part of the fifty years, it was a matter of figuring out what worked as the world in general and the art world in particular changed. After the frame shop and gallery in Aspen, I went on the road selling art to galleries at what was the zenith of that profession. That came to an end as media changed and it became less important to get your art from New York and Paris. Now that we see NFTs and crypto come tumbling down — I hope — the brick-and-mortar business is coming back, not that it ever went away.

"Online shopping has changed the landscape, for sure, and one needs a digital presence in this day and age, but there is nothing like seeing the real thing in person."

"Online shopping has changed the landscape, for sure, and one needs a digital presence in this day and age, but there is nothing like seeing the real thing in person."

From All Angles: Fifty Years in the Art Business opens with a reception from 5 to 8 p.m. Friday, September 8, at the William Havu Gallery, 1040 Cherokee Street. The exhibit will be up through October 21; find more information at williamhavugallery.com.