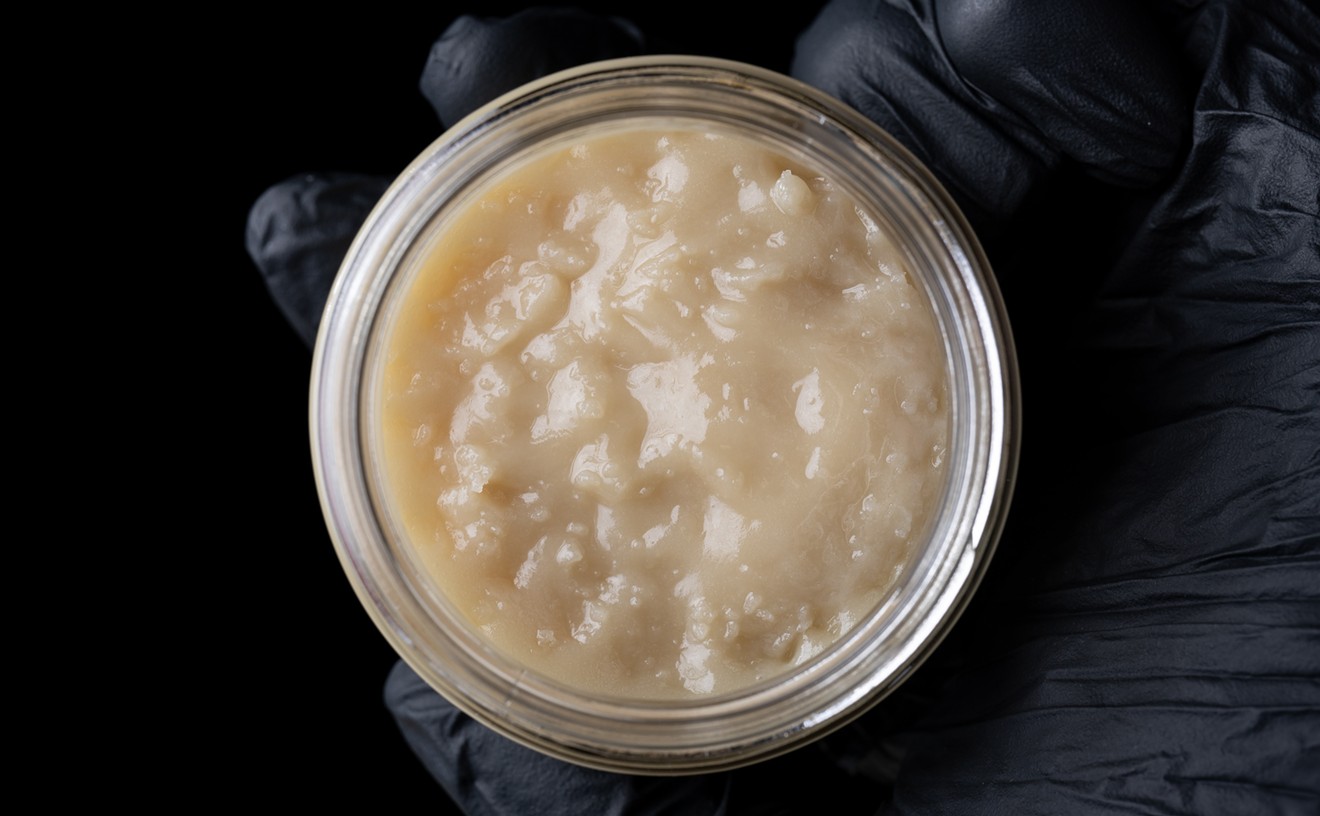

Using a breathalyzer alone to effectively detect cannabis impairment could be a pipe dream, according to a recent pilot study spearheaded by the University of Colorado.

A valuable tool over the past half-century for law enforcement officials measuring blood alcohol levels, breathalyzers rely on chemical reactions from alcohol vapors in our breath. And despite claims from a handful of breathalyzer manufacturers to the contrary, newly published research in the Journal of Breath Research says that detecting THC impairment isn't as simple.

Since THC can affect everyone differently, detecting pot impairment isn't as simple as using a breathalyzer, blood test or urine sample to determine alcohol levels. Not only that, but detecting recent consumption in a regular cannabis user's breath can be extremely difficult after about an hour, according to study co-author and CU neuroscience and psychology professor Cinnamon Bidwell.

"We are not there yet in terms of reliable tools, so I think making false claims or selling products that aren't reliable is not a good situation," she explains. "We have this image of how well a breathalyzer works for alcohol, but you have to let people miss and let places like CU Boulder do the work. We don't have a for-profit force in this game. We actually want to do the science and understand the science."

Bidwell, who has conducted cannabis impairment studies for CU in the past, partnered with National Institute of Standards and Technology chemical engineers Tara Lovestead and Kavita Jeerage to study the current effectiveness of THC breathalyzer technology. Armed with about $2 million in federal research grants, the team used a filter-based device to collect breath samples from eighteen cannabis users. Each participant was asked not to smoke or vape weed the day before their submissions, and to buy a specific strain of flower containing 25 percent THC.

After securing their herb, a CU-owned mobile laboratory set up in a sprinter van outside of the participants' homes. The participants would smoke or vape their cannabis in their homes and then visit the mobile lab to breathe into the cannabis breathalyzer, with the samples sent to NIST for analysis. According to the study, only eight of the eighteen cannabis users showed the predicted increase in THC breath levels after cannabis use. In three samples, THC was not detected at all, while several other samples showed lower THC amounts than baseline levels. While Bidwell cautions that more research needs to be done in light of the study's small sample size, she's convinced that breathalyzers have a lot of work left.

Over half of the country's population now lives in states with legal cannabis, and more states continue to consider legalization measures. However, detecting THC impairment has proven elusive for scientists, whose work is still restricted by the federal government because of the plant's Schedule I status. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recently recommended that the Drug Enforcement Administration reschedule cannabis to Schedule III, which would allow for easier research pathways, but the DEA must first approve any rescheduling.

Colorado state law currently considers any driver with more than five nanograms of THC in their blood to be intoxicated. However, studies and even Westword experiments have shown that THC levels in the blood remain high for regular users over twelve hours after consumption, while THC blood levels in novice users spike immediately after smoking but can drop below five nanograms within hours. Colorado Department of Transportation officials and state lawmakers have admitted that the five-nanogram limit is not a scientifically accurate way to measure impairment, but a better alternative has not yet emerged.

In September, NIST granted CU Boulder $600,000 to continue research on cannabis breathalyzers. Despite the CU study's results and lack of universally approved roadside cannabis tests, Bidwell is hopeful that breathalyzers can still detect recent cannabis use by drivers. Still, that's only half of the equation.

"Impairment is different than recent use," she adds. "With THC blood levels and impairment, there's not a really strong link. It's not like it is with alcohol, where we have a really strong correlation. But even if we're not totally sure on the impairment question, it would be nice to have a reliable tool to tell whether someone recently used," Bidwell says. "THC exposure does not equate to impairment. The link in literature, it's just not there...which is why I have to scoff at private companies saying they've got this figured out."

Law enforcement officers could combine such information with roadside cognitive testing to better determine cannabis impairment instead of relying on a blood test, Bidwell says, but adopting such protocols across the country might not be easy.

"It would be really great if we had this free roadside test, whether it was a motor or reaction measure — something objective and quick that didn't rely on an officer's interpretation. I love the idea," she says. "But there is nothing out there that has really been studied or validated to that level yet."

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "leaderboardInlineContent",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "tower",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

}

]