A new study funded by the Morris Animal Foundation is looking to fill that gap. The Denver-based foundation is one of the largest nonprofit animal health research organizations in the world, donating approximately $150 million to fund nearly 3,000 animal studies over the past 75 years. Morris recently funded research looking into CBD's pain relief potential for dogs that have undergone a common ligament surgery known as a tibial plateau leveling osteotomy (TPLO). To learn more about the research and how pet owners can benefit from it, we chatted with study leader and University of Saskatchewan professor Dr. Alan Chicoine.

Westword: What are you trying to discover with this study?

Dr. Alan Chicoine: Our interest was due to a lot of interest in CBD for quite some time in veterinary medicine. Much like in the United States, it wasn’t technically legal for use in Canada in either animals or people, but people were using it. There were a lot of anecdotal reports, both positive and negative, lots of different types of products being used, so it was kind of like the Wild West. In Canada in 2018, cannabis usage was legalized for people across the board, but the way that the legislation was written, it excluded veterinary medicine. Technically, it was not legal for veterinarians to prescribe CBD or cannabis derivatives for animals, but it was still being widely used. Because of that, we began receiving questions from veterinarians or clients, like, does this stuff work? Should we use it for this? What kind of dosages should we use? And we had no idea. There’s lots of research going on, but the veterinary aspect was missing. If there’s any benefit there, what sort of dose regimen would be appropriate? If it doesn’t appear to be working, that’s great, too, because at least we’ve generated that knowledge that people are trying a product that isn’t going to be effective. They’re buying it when they don’t need to, or, more important, might be choosing that over a product that could be more effective for the same purpose.

This study is specifically looking at TPLO patients. What is a TPLO procedure?

The TPLO procedure is a very common procedure for dogs that tear their cranial cruciate ligament, which is analogous to our anterior cruciate ligament, or ACL. It’s a really important ligament in the knee, so it’s basically the animal version of an ACL tear. Like people, dogs and cats can tear their cranial cruciate ligaments either very suddenly and acutely, like jumping off a deck, or it can be a partial tear that slowly gets worse over time. Depending on the species and size of the animal, the vet may want to do medical management, which is usually just cage rest and limited activity, slowly letting the joint heal on its own. But for larger dogs, that doesn’t work very well, and a surgical approach is preferred. Basically, a TPLO is cutting part of the tibia bone, which is the big bone underneath the knee joint, and re-angling it a bit so that it replaces the cruciate ligament in stabilizing that joint.

Why did you decide to focus on TPLO patients with this study?

We know quite a bit about how dogs recover after these surgeries, so we could get a good comparison of dogs treated with CBD oil versus our negative control, and know what to look for to see if they’re doing better. The most common surgeries, of course, are spays and neuters, but those are pretty simple procedures, very routine, and animals recover very well and very quickly from them. We chose the TPLO as a model because there are so many dogs that have cruciate ligament injuries, and it's sort of the gold standard at our teaching hospital to fix those. It’s an invasive surgery, and we have really good analgesics that we use already, but it’s a surgery where maybe there’s a little bit of room for improvement in terms of the analgesia and return to function. If CBD oil is going to show a benefit, we thought this type of surgery might be a candidate where it could actually show a difference.

So the dogs in this trial are either getting CBD oil or a placebo, but is that in addition to the medication they would normally receive after this surgery?

Absolutely. That’s a big misconception. People think, "Oh, you’re studying this instead of studying other different types of analgesics," but no. We’re studying the standard analgesic protocol in addition to CBD, versus the standard analgesic protocol by itself. All of the animals are getting the gold standard of analgesia. The downside of that for our study is that it makes it really hard for CBD to show that it's beneficial, because the bar is really high. So it's going to be tough to demonstrate that CBD really does take it to the next level, but unless we do the study, we’re never going to find out.

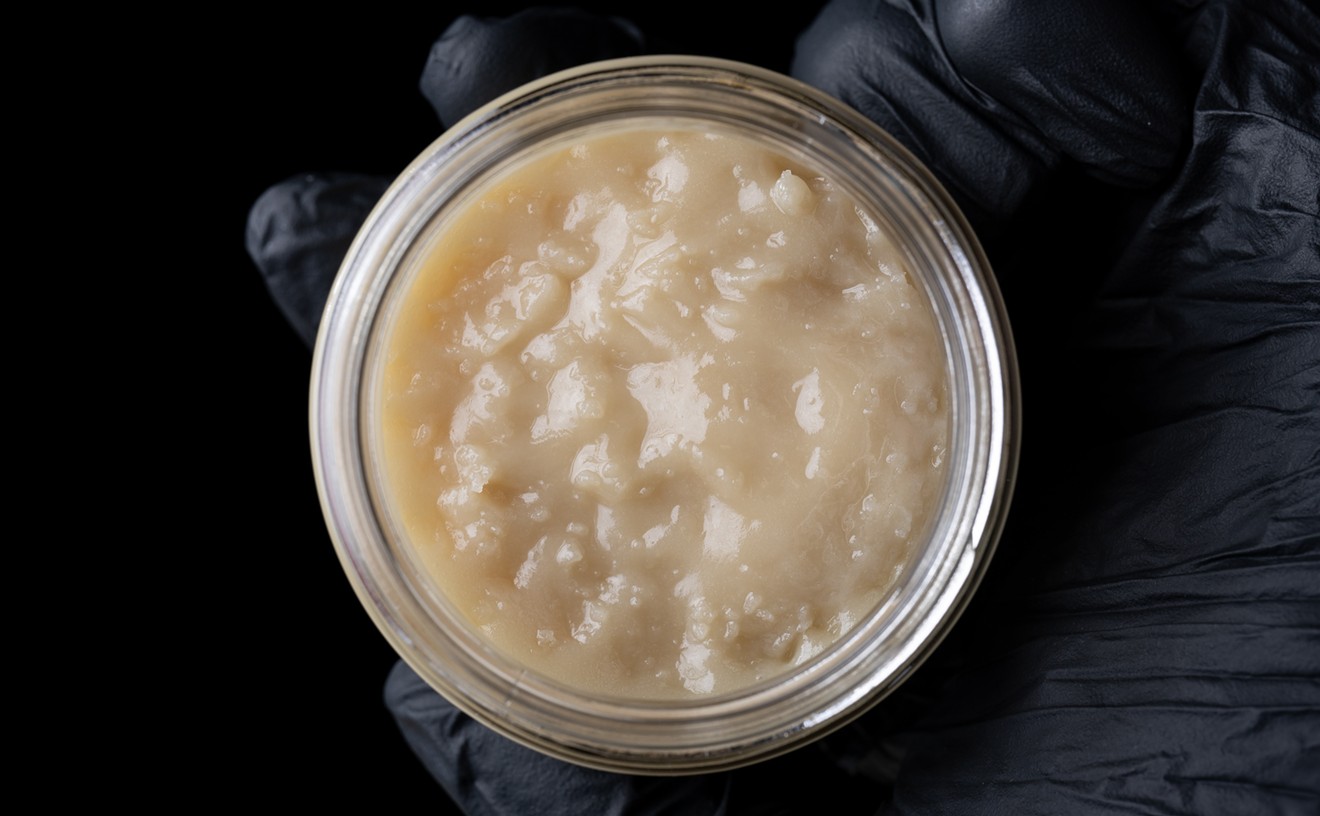

What CBD product are you using in the study?

We’re using a formulation that’s an extract in olive oil. The reason we’re using it is this particular product has been used in some other studies. [It] is a consistent product at a 20:1 ratio, so 20 milligrams CBD to one milligram THC. The cannabis provider we chose to partner with for this study provides significant analysis for every batch sent to us; we know exactly what’s going into it, everything is tested, and the stability of the product has been evaluated beforehand.

So the product we're using, if it’s going to work, great, but if it doesn’t, it won’t be because the product wasn’t legit. This is a full-spectrum extract, so there are other cannabinoids in there, too. There may be some benefit to having THC in the product; it certainly introduces some risks as well, but it is at a very, very low level in this product. We were more interested in the CBD aspect of it, but it’s an open-ended question as to whether or not, if CBD is beneficial, THC will help with that. We don’t know at this stage, so first we’re trying to see if there’s a benefit to utilizing any cannabinoid formulation.

Ralph the goldendoodle on a pressure-sensing walkway used to assess pain levels and limb function after surgery.

Dr. Alan Chicoine

This is the million-dollar question for our study: How do you actually show if the CBD is helping to improve that? We’re only looking at the first two weeks after the TPLO surgery. Logically, there’s no reason to think that the CBD would change the bone healing after months of time, and for a more practical reason, the dogs come back to the clinic for a recheck at two weeks. That’s when they look at the surgery site, look at the incision and make sure that everything is healing okay. Our primary measure in the clinic is a pressure-sensing walkway. Basically, the dog walks on a mat attached to pressure sensors, and it measures the force produced from every paw as it’s stepping down. The reason we’re using this as one of our outcome measures is that we want to see how much pressure a dog can put on their limb while they’re walking. If they can put more pressure on it, they’re obviously in less pain and have more function of it.

The other things our rehabilitation veterinarians will look at is they will move the limb back and forth and measure the angle of that knee joint. They will also look at the swelling around the knee after surgery. After two weeks, we want to see how that heals, and if the site is still swollen or it has come down a fair bit. They will just use a simple tape measure for that. Those are our quantitative metrics that we’re looking at in the clinic. The owners will also be doing scoring at home using a modified version of a scoring scheme commonly used with musculoskeletal pain in dogs. The owners will answer questions on how painful they think their dog is each day, how well they’re doing the activities they’re allowed to do, basic functions like walking outside to go pee, their appetite, those kinds of things. That owner involvement was critical, because the owners are the ones who can best assess how their animal is doing.

Are there certain signs of an adverse reaction to the CBD that the researchers are looking out for?

We did some preliminary work in 2019 looking at plasma levels of the various cannabinoids in dogs. What we did find was that with the higher doses we selected, some of those dogs had a little bit of hyperesthesia, or reacting a little bit more to stimuli than they otherwise would. They weren’t clearly intoxicated or anything like that, but there were neurological changes evident that I think most owners would pick up on in their dogs: a delayed reaction to sound, light or movement, and an over-response to normal stimuli. We were using ten milligrams per kilogram [of body weight] in that dose group, but we weren’t going to use that for this study. Then we did a two-week safety study in a colony of beagle dogs at the vet college, at two milligrams of CBD per kilogram and five milligrams of CBD per kilogram. Some of the dogs in the five-milligram group were a little quieter than the control dogs were, but not anything that owners would say is an adverse effect; no vomiting, diarrhea or anything like that noted. We also did blood work on those dogs, and there were no major adverse effects that we saw. So we felt very confident in terms of animal safety. So far, we have not seen any adverse effects reported by the owners.

It seems like it’s pretty widely accepted that THC is not good for dogs in large amounts. How did vets figure that out? Were there controlled studies done on the effects of THC in dogs, or is it just from experience treating animals that have accidentally ingested THC?

Every vet clinic across North America sees cases of presumable THC intoxication in dogs, but there’s no test to actually verify that it was THC that caused the intoxication. Through blood work, we found that of the cases we had that were presumed to be cannabis toxicity, 37 out of 38 cases had quantifiable levels of THC in their plasma. It proved pretty conclusively that when the veterinarians thought they were dealing with cannabis toxicity, that’s exactly what it was. What’s missing from that, however, is that this testing was done whenever the owner brought the dog in. So the timing of the sampling was either unknown or all over the map. Therefore, the concentrations of THC that we determined really weren’t predictive of the degree of intoxication of the dogs, because the dog could have been very intoxicated a few hours ago, but by the time it gets to the clinic, the concentrations could have dropped. We don’t have a good handle on that yet in terms of what plasma concentrations are going to be indicative of toxicity.

Do you think it’s possible that studying the effects of CBD on dogs could lead to a better understanding of how to treat dogs exposed to THC?

Looking at the intoxication cases that come into the clinic, one of the questions we had was, where are these dogs getting intoxicated from? Is it a case of a dog that’s taking a high-CBD product — either the owner administering it to the dog or the owner is taking it themselves and the dog just happens to get into it? Is that leading to intoxication? So we were measuring CBD levels in the plasma of those dogs as well, and for the most part, the dogs did not have lots of CBD in their plasma. Nothing at all like the dogs in our preliminary study. So what we concluded was, these are recreational THC products that may or may not have a little bit of CBD in them, but they were not CBD medicinal products that were leading to intoxication. So we really want to draw a distinction between CBD as a potential medicinal product that may or may not have small quantities of THC versus high-THC products primarily used recreationally by people that are leading to the intoxication cases that veterinarians are seeing. That’s a really big communications challenge — not just for veterinarians, but for the general public as well.

After the study is complete, what is the next step?

What we’re going to be looking at is, if we do see an improvement in the dogs that have CBD included in their treatment regimen, can that be refined? Are we happy with the response that we’re seeing, or is there room for further improvement? That might mean looking at a different dose, a different formulation with a different CBD-to-THC ratio, or any way to refine the dosing regimen. The other potential next area is other conditions where this could be used. A lot of my colleagues looking at cannabinoids in veterinary medicine are looking at a variety of different areas, like neurologists looking at dogs and cats with epilepsy, seizure control, and lots of people looking at arthritis.

In terms of post-surgical usage of CBD, are their other types of surgeries where it could be beneficial? Just because it was helpful for this one surgery doesn’t mean it will be helpful with others. So that would need to be tested. We didn’t choose to evaluate this with spays and neuters, because we don’t think there’s a lot of room for improvement with the analgesia there. But maybe we revisit that. If it’s helpful after the TPLO surgeries, maybe we look at a different surgical model. If it doesn’t look like it’s helpful, then we need to evaluate why that is. But we won’t know the answer to that until we get deeper into the trial and get more cases enrolled.

Would you be interested in replicating a similar study in other animal species?

Absolutely. I was a mixed-animal practitioner, and I certainly have an affinity for working with cattle. The problem with cannabis work in cattle — and we sort of toyed around with maybe doing that — [is that] the cost is just prohibitive at this stage. Same with horses. Even in some of the larger dogs, the cost is getting pretty high, so with large animal species, on a practical level it’s not feasible yet. But cats, absolutely. We would look at a surgical model with cats, but the challenge with that is there’s not one particular routine surgery that’s performed commonly in cats other than spays and neuters. They do some cruciate surgeries, but none of them stand out like the TPLO surgery did for dogs. It would be hard to get that sort of data set in cats, just because you’re not doing that many of one consistent surgery. But if this works in dogs, we would love to expand it to some of the other species.