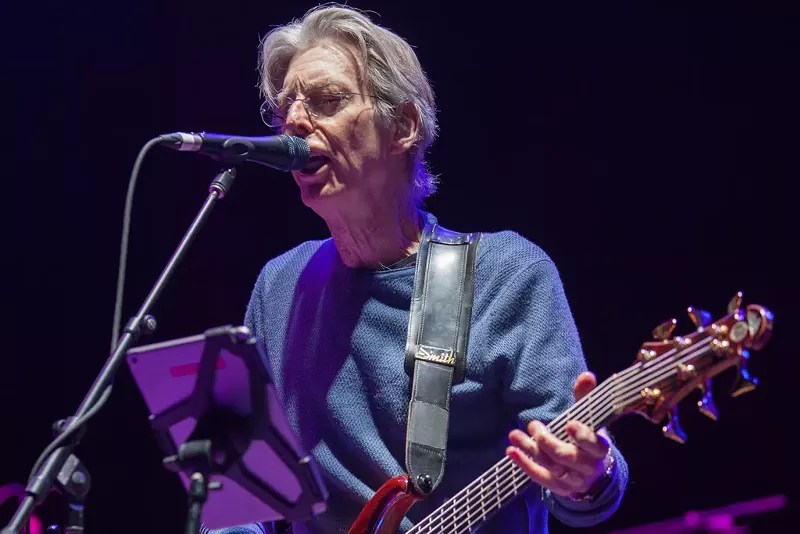

Phil Lesh, the bassist of the Grateful Dead and vocalist/co-writer (alongside Robert Hunter) for such hits as "Box of Rain," "Truckin'" and "St. Stephen", has died at 84, per an announcement on his Instagram on October 25.

"Phil Lesh, bassist and founding member of The Grateful Dead, passed peacefully this morning. He was surrounded by his family and full of love," the statement reads. "Phil brought immense joy to everyone around him and leaves behind a legacy of music and love. We request that you respect the Lesh family’s privacy at this time."

Lesh was a founding member of the seminal band, which started as the Warlocks with Jerry Garcia, Bob Weir, Ron "Pigpen" McKernan and Bill Kreutzmann in 1965. Before he joined Garcia and took up bass, Lesh had been a composer and classical violinist and trumpeter, studying with the avant-garde composer Luciano Berio.

And Lesh remained avant-garde throughout the band's thirty-year history, saying in Garcia: An American Life that his bass style was influenced by both Jack Cassady of Jefferson Airplane and Bach's counterpoint. After Garcia died on August 9, 1995, Lesh formed Phil Lesh & Friends in 1998 to keep the music going. In 2006, he announced that he had been diagnosed with prostate cancer, which went into remission after a procedure the next year. Lesh joined Furthur with the remaining Dead members from 2009 until 2014, and took part in the Fare Thee Well tour in 2015.

Lesh had canceled shows earlier this year citing illness; his final performance was on July 21, at McNears Beach Park in San Rafael, California, for the Sunday Daydream festival. Before his last song, "Sunshine Daydream," Lesh said, "I am the luckiest man in the world."

The Dead started shining its light through the cool Colorado rain back in 1967, when the band first played the Family Dog in Denver. That venue didn't last long, but the Dead attracted a fanatic, loyal following that kept it alive until (and after) Garcia's death on August 9, 1995. The music never stops for Deadheads, who have been keeping the legacy going, sharing the virtuosic jam band with younger generations, forming tribute bands or creating unique artworks inspired by the Dead.

Discover the Dead's Colorado connections below:

Bob Weir Met John Barlow While Living Here

Originally from Atherton, California, a suburb of San Francisco, Weir had dyslexia and consistently failed in school. For his sophomore year of high school (1962-’63), his parents sent him to boarding school at Fountain Valley School of Colorado in Colorado Springs. He failed out yet again, and returned to San Francisco, where he met Jerry Garcia. But his stint at Fountain Valley wasn't for nothing: Weir met close friend and lyricist John Barlow at the school. Barlow, who penned such songs as "Cassidy," "Estimated Prophet," "The Music Never Stopped," "Black-Throated Wind" and more, became a mainstay of the Grateful Dead, and introduced the band to LSD advocate and Harvard professor Timothy Leary.

Weir returned to the school for his would-be graduating class's fiftieth reunion and the school's 85th anniversary in 2015. He was inducted into the school's arts guild, received an honorary diploma and even played a few Dead songs with a local band, the Fever, at the event.

The Family Dog

Garcia, keyboardist Ron "Pigpen" McKernan, Weir, Lesh and Kreutzmann (Hart joined the band in ’67) ditched their original moniker, the Warlocks, and first performed as the Grateful Dead during one of author and psychedelic advocate Ken Kesey's infamous Acid Tests, in which participants took indistinguishable amounts of LSD, in San Jose on December 4, 1965. Through 1966, the Dead mostly played venues around California, primarily in the Bay Area. There they met an artist collective called the Family Dog, which came to California from Detroit and hosted concerts in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury neighborhood (where the Dead members also lived) as well as along the coast.

After making its mark in San Francisco, the collective partnered with Colorado concert promoter Barry Fey on the Family Dog venue at 1601 West Evans Avenue (now home to the strip joint PT's Showclub). The concert hall opened on September 9, 1967, and the Grateful Dead played its first Colorado shows there on September 22 and 23; the band followed those up with a casual performance in City Park.

The club closed in 1968, after bringing the psychedelic rock scene to Denver with musicians such as Jefferson Airplane, Cream, the Doors, Canned Heat and more. The Dead album Family Dog at the Great Highway is a recorded set at the San Francisco venue from April 18, 1970, just a day before that venue also shuttered.

Colorado Concerts

Two years after playing the Family Dog in Denver, the Dead played at the University of Colorado Boulder on April 13, 1969, with an electrifying show. That year, the Dead played a total of about 140 shows, and on July 3, it offered a memorable set in Colorado Springs at Reed's Ranch, a small venue in a barn, not far from where Weir spent his sophomore year of high school.

The Dead played its first show at Folsom Field on September 3, 1972, with 31 songs over three sets. Six years later, the band took to the state's most iconic venue, Red Rocks Amphitheatre, on July 7 and 8 and August 30 and 31. From then until 1987, the Dead would play twenty shows at Red Rocks, out of a total of about fifty shows in this state.

Jerry Garcia Bought a Pedal Steel Guitar in Lakewood

After that first CU concert, Garcia made a big purchase. He had been eager to master pedal steel guitars since he and his friend Pete Grant heard Buck Owens's "Together Again" on the radio in 1964 (Grant ended up playing the pedal steel on Aoxomoxoa). In 1966, Garcia sold his Fender pedal steel to Lowell "Banana" Levinger of The Youngbloods; by '69, he was ready to give it another shot. After playing the show in Boulder, he bought a Zane Beck Double-Ten pedal steel guitar at a Guitar City in Lakewood. In the book Jerry on Jerry, Garcia recounts to author Dennis McNally:

Here's what happened. I’ll tell you. It’s really very simple. I’d fooled around a little bit with pedal steels and stuff, but I couldn’t make any sense of them. And then we went to a music store in Denver, and there was a completely strung-up, tuned-up, nicely put together, set-up and everything, pedal steel. You know, state-of-the-art 10-stringer, with two necks and everything. And I sat down at it, and I played with the pedals a little bit and I fooled with the tuning. I dug the tuning and I played with the pedals a little. And I said, “Oh, I see!” You know, suddenly I finally started to understand a little of the sense of it, the tuning and the way it worked. And that was the first time I’d ever been near one and I saw how this works, you know. So I said, “I want to buy this fuckin’ thing, but can you send it to me with it in tune, you know, ‘cause I’ll never remember this tuning.” So they packed it up and sent it to me in tune. I took it out and unpacked it, and sure enough—it was really the thing of discovering that I could relate to it because it’s very different than a guitar. It’s not a guitar, and it’s not a banjo, either. It’s not like either one of those instruments in any way. And it’s only superficially like anything that I played at the time. And it’s really very different. It has very different logic to it.

Being in that music store finally, with one correctly tuned and one together the way they’re supposed to be, and just a chance to touch it and fool with it for about 15 minutes, I finally could start to see the sense of it. And seeing the sense of an instrument is the whole instrument. You know what I mean? If you don’t understand the logic of an instrument, the sense of an instrument, how it works, what makes it do what it does, you’ll never understand the instrument. Never. It would be like picking up a saxophone and, “What is this?” You know?

Still, Garcia was never satisfied with his work on the instrument, and only played it live sporadically after the Dead's acoustic tour in 1970.

Rare Acoustic Set

In 1969-’70, the Dead experimented with doing acoustic sets to shake things up. As Weir put it: "We're gonna take a break from all this sweat and steam and uproar and tumult, and we're gonna break out our acoustic guitars and regale you with some wooden music." This saw the introduction of the hit "Dire Wolf" as well as a revival of songs that hadn't been played in some time, including "China Cat Sunflower," "New Minglewood Blues," "Me & My Uncle," "Silver Threads & Golden Needs," "Candy Man" and more. The band performed its only acoustic set in Denver (followed by an electric set) at Mammoth Gardens — now the Fillmore Auditorium — on April 24, 1970.

The Dead's LSD Supplier Had a Lab in Denver

"Acid King" Owsley Stanley is known for manufacturing the LSD for Kesey's Acid Tests and for Dead members as well as many other rock groups, including the Beatles and the Jefferson Airplane. But Stanley was more than just an acid-slinging roadie: He financed the Dead early on, became the band's sound engineer under the moniker Bear, and built sound equipment, including the famed Wall of Sound. He even helped design the thirteen-point lightning bolt logo with friend Bob Thomas. With his background in ballet, Stanley inspired the Dancing Bear image, also drawn by Thomas, which has become a significant symbol in Dead culture.

After LSD was made illegal in California in 1966, Stanley and chemist protégée Tim Scully moved their lab from Richmond, California, to a basement in Denver. Scully told Westword in 2017 that he and his friend Don Douglas encouraged the move, found the location and set up the lab near the Denver Zoo. Because Stanley only had so much lysergic acid — the base for LSD — remaining and had to retrieve it from a safety-deposit box in Phoenix, he first had Scully and Douglas synthesizing the psychedelic STP. Stanley delivered the lysergic acid in May 1967, and by September, the lab had generated a million doses of LSD, which Stanley and Scully took back to California to turn into tablets. The feds busted Stanley in California in December 1967, and 67 grams of LSD from the Denver lab were taken. Although Stanley made bail, he turned his focus solely to sound work for the band, while Scully rented a house at 1050 South Elmira Street to mount a second lab. That lab was busted, but when Scully and his two lab assistants appealed their charges, the Colorado Supreme Court found that the police had conducted an illegal search and ordered the police to return the lab equipment.

And a final Dead footnote: One Westword writer was such a fan of the Dead that after he passed, some of his ashes were brought into Bob Weir's guitar case during a concert at the Paramount. Rest in peace.