This past week, I visited Nashville and had the pleasure — the pure pleasure — of seeing Loretta Lynn perform live at the Grand Ol' Opry. As I listened to her still-vibrant voice deliver "Coal Miner's Daughter" and songs from her fine new album, Full Circle, I marveled anew at how music from country's living legends continues to resonate.

Now, that group of legends is diminished by one. Merle Haggard died today, on his 79th birthday.

Haggard's passing comes as such a shock in part because he was in the midst of yet another career upswing. Last year, Django and Jimmie, a duets album with Willie Nelson, debuted at number one on the Billboard country-albums sales chart. Moreover, Haggard recently said during a Rolling Stone interview that he and Nelson were at work on a sequel.

"Our names are like magic together," he told the magazine, adding that he was eager to get back on the road following his hospitalization for double pneumonia.

"I've lost a lot of weight. I'm going to appear different on stage," he noted before adding, "Well, I'm still on top of things. I'm doing a lot of writing and I'm just proud to be alive and hope that people realize that. I really sincerely thank everybody for the prayers."

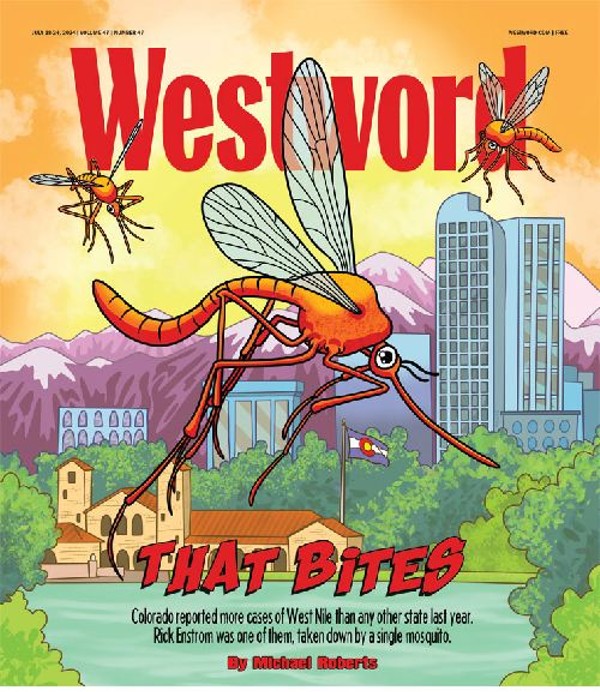

Many more prayers will be offered in Haggard's name now. But an even better way to celebrate his time in our midst is to listen to his work — including the brilliant efforts compiled on Down Every Road: 1962-1994, a box set I lauded for Westword in "Old Hag," a piece originally published in 1996 and shared below in its entirety. Beyond sheer appreciation, the article offers lots of background on Haggard — his poor upbringing, his stint in prison, his enormous influence on what's come to be known as the Bakersfield sound, his time as an unlikely conservative icon thanks to the success of "Okie From Muskogee," and the mark he's left on American music.

His influence will go on. Last year, I interviewed an unlikely Haggard fan: Jonathan Davis, lead singer of Korn. Davis is putting together a country album that focuses on Bakersfield, and when I asked if he planned on including any Merle Haggard, he replied with two words: "Of course."

Well said, Mr. Davis.

One more thing. While in Nashville, I purchased a stack of 45s for my home jukebox, and among the treasures I found — for just a quarter — was "I Wonder If They Ever Think of Me," an unexpectedly complex Haggard song mentioned in the review below. When I spin it this evening, you won't have to ask if I'll be thinking of him.

"Old Hag"

By Michael Roberts

May 16, 1996

At the Academy of Country Music awards presentation in late April, a slew of country stars were rounded up for a tribute to Merle Haggard, the designated recipient of a lifetime achievement statuette. Clint Black, wearing his trademark chapeau, introduced the segment with heartfelt superlatives that were echoed by several other celebrities, including Johnny Cash, whom Haggard first saw perform while serving an extended stretch at San Quentin. Still, there was one important person who neglected to weigh in with appropriate comments: Haggard himself. Buck Owens — whose work, like Haggard's, was nurtured in the California desert community of Bakersfield — accepted the bauble in Merle's place. And although Owens offered his own praise of Haggard, he didn't explain why the honoree hadn't bothered to show up. The implication behind Owens's omission was obvious: Apparently, Haggard had stayed away from this shindig for no other reason than that he didn't want to be there.

Such orneriness lies at the base of Haggard's appeal. While he has been embraced by the Nashville establishment, he's never truly been a part of it. From the beginning, he was more than just an outsider — he was (as Willie Nelson noted during the ACM salute) literally an outlaw. Craggy, contradictory, deeply troubled and yet deeply compassionate, he's well-named; after all, Webster's defines "haggard" as "unruly, untamed." As such, he's instinctively wary of praise. Most artists would be thrilled by the appearance of a boxed set as thoughtful and impressive as the four-CD Capitol release Down Every Road: 1962-1994, and maybe Haggard is, too. But he's not going to show it. Hell, Haggard didn't even bother to give an interview to Daniel Cooper, a Country Music Foundation bigwig who wrote Road's effusive liner notes. Hence, Cooper was forced to cobble together quotes from earlier articles — ones that celebrated Haggard the living, breathing troubador rather than enshrining him as an exemplar of an earlier, better era of country music.

Unfortunately, this package doesn't make an especially strong argument for Haggard's greatest days being ahead of him; the Road pieces from the Eighties and Nineties are above average, but they don't reverberate with the effortless panache that marks the majority of what preceded them. In addition, there's more than a smidgen of evidence that the across-the-board success of "Okie From Muskogee," the cheerfully reactionary 1969 anthem that stamped Haggard with a persona he still wears, led to a certain self-consciousness that limited his subsequent effectiveness. Nevertheless, Haggard remains a defining C&W figure. His imitators are legion, but they pale before their model because they lack Haggard's secret ingredient: authenticity.

Hard times were Haggard's birthright. When he came along in 1937, his parents, transplanted Oklahomans James and Flossie Haggard, and two older siblings were living in a converted boxcar in Oildale, California, just outside Bakersfield. Nine years later, James — a fiddle player who hung up his instrument when he moved his brood from dustbowl Oklahoma to California — died of a stroke. Merle's mother was forced to work full-time, leaving her youngest confused, angry and largely unsupervised. As a result, his teen years became a blur of musical discovery (he fed on a steady diet of Bob Wills and Lefty Frizzell) and juvenile delinquency. At age twenty — married with child (and a second on the way) — he capped his criminal career with a transgression of astounding stupidity. He and a buddy, both stewed on booze, tried to bust into a restaurant at what they thought was about 3 a.m. In actuality, it was 10 p.m., and the restaurant was still open.

Three years in the Big House gave Haggard an appreciation for time; when he emerged from San Quentin, he began living as fast as he could. His prodigious energy also helped him gain a musical reputation among Bakersfield's C&W crowd. The sound that emerged from this community rocked more persuasively than the standard Nashville brand of music that was popular then, but it wasn't rock and roll. Instead, it harked back to an earlier tradition: The prominent guitar riffing and generally astringent arrangements were melded to swooping backwoods vocal lines that bore the influence of Jimmie Rodgers and his brethren. This approach suited Haggard; his voice was capable of both punchy accents and a surprising delicacy that became especially poignant at higher registers. In short, he could effectively portray toughness and tenderness, and he often chose to do so in the same song.

"Skid Row," the initial cut on Road's first disc, was written by Haggard when he was just fourteen, but even this early effort rings with an empathy for the common man that's still one of his most notable attributes. It also demonstrates his skill at wringing fresh thrills from subject matter that was already timeworn in the Sixties. "I'm Gonna Break Every Heart I Can," from 1965, might have seemed like a commonplace revenge fantasy in other hands, but in Haggard's it becomes a saucy charmer. Likewise, "Swinging Doors" and "The Bottle Let Me Down," recorded during the same period, employ standard-issue booze imagery that satisfies primarily because it's abundantly clear that Haggard isn't dealing in abstraction. Even if the lyrics aren't specifically autobiographical, he's still telling his own story. "Branded Man," a classic ex-con's lament, is even more vivid, because it's closer to the truth. And while the words that make up 1968's "Mama Tried," on disc two, contain a bit of hyperbole (Haggard did turn 21 in prison, but he wasn't sentenced to "life without parole"), they capture in plainspoken language Haggard's essence. On these ditties, his romanticizing of past troubles seems completely natural. Quite simply, Haggard was using the raw materials he had at hand as the basic ingredients in his workingman's art.

"Okie," with its infamous opening verse ("We don't smoke marijuana in Muskogee/We don't take our trips on LSD/We don't burn our draft cards down on Main Street/'Cause we like living right and being free"), is something else entirely — a right-wing novelty. (Haggard once claimed the track was intended as a joke.) But it made such an impression in 1969 that Haggard recorded a number of near-sequels, including "The Fightin' Side of Me" and "I'll Be a Hero (When I Strike)," that turned him into a somewhat reluctant spokesman for the hit's worldview. As a result, he soon felt the need to debunk his bare-knuckled reputation even as he was being asked to perform private concerts for President Richard Nixon. This balance proved a difficult one to strike. For example, 1970's "The Farmer's Daughter" finds the central character allowing his beloved child to marry a city boy even though "his hair is a little longer than we're used to." By contrast, 1971's "Daddy Frank (The Guitar Man)" features Haggard trying hard — too hard — to champion the kind of folks that Nixon referred to as "the silent majority." Literally silent, in this case: The matriarch of the family band about which Haggard warbles is mute — a perfect match for Daddy Frank, who's blind.

Despite stumbles like "Daddy Frank," Haggard's songwriting knack certainly didn't abandon him during this period. "I Wonder If They Ever Think of Me" may have seemed like another sop to conservatives when it was released in 1972, but its sensitive treatment of a homesick POW is actually an affecting character study that transcends politics. And "If We Make It Through December," a paean to an unemployed family man, is as liberal-minded as anything in Haggard's catalogue. At the same time, Haggard's singing, though perhaps a bit gruffer than during his Sixties prime, remained strong and singular throughout the decades that followed. The late-Seventies offering "Footlights" suffers from the kind of relatively obtrusive production that crops up more frequently on the box's final CD, but Haggard's weathered pipes are still capable of slicing through the electric piano and cheesy guitar solo that decorate the effort, giving it a modicum of dignity in spite of itself.

"In My Next Life," the last song on Road (and the only one that dates from the Nineties), is not nearly so enjoyable. Written by Max B. Barnes, it's the kind of lachrymose composition that the Tracy Lawrences and Toby Keiths who rule current country manage to sell to a gullible public with alarming frequency. Haggard does what he can with the number, but it remains depressing to hear, if only because he deserves so much better. Testimonials are fine, but as Down Every Road establishes so well, they don't mean a damn thing compared to the stories a well-traveled man can tell.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "leaderboardInlineContent",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "tower",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

}

]