Avery Borkovec should still be alive. After all, he was only 22 years old in November 2022, when he drew his final breath while in custody at Boulder County Jail, and the ailment that led to his death — a bacterial infection — could have been treated successfully with the sort of antibiotics that have been widely available since shortly after the discovery of penicillin in 1928.

Moreover, doctors correctly diagnosed Borkovec's condition weeks before his passing.

What went wrong? Pretty much everything, according to a new lawsuit on behalf of Borkovec's closest living relative, his great-uncle Chris Borkovec, by Holland, Holland Edwards & Grossman, LLC, a Denver-based law firm. The complaint, filed today, September 27, in U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado, contends that authorities in Broomfield, where Borkovec was initially incarcerated, knew about his malady but didn't get him immediate care, then failed to inform their peers in Boulder, where he was transferred, about the illness.

Making matters worse, medical staffers in Boulder allegedly cold-shouldered or slow-rolled responses to multiple messages about Borkovec's dramatically worsening health despite unmissable signs of distress — not the least of which was a skin tone so pale that his fellow inmates referred to him as "Casper," aka the friendly ghost.

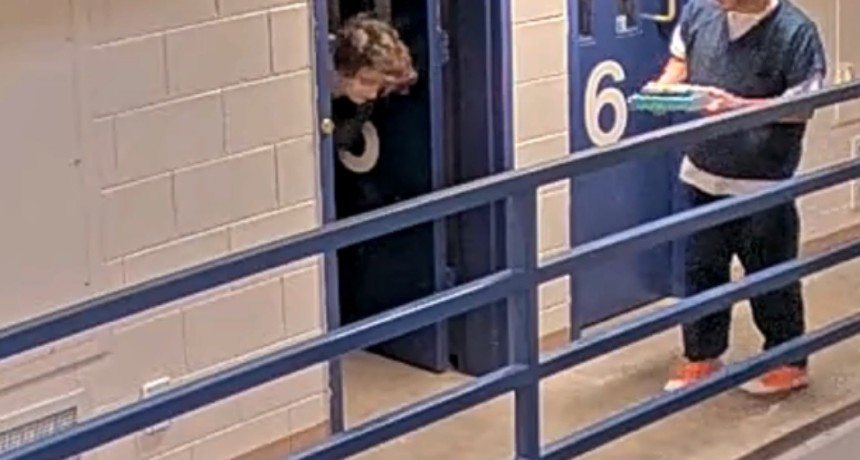

His deterioration didn't happen quickly. According to attorneys, Borkovec spent his last month in agony as he faded before the eyes of those jailed with him. The suit is accompanied by statements from five such witnesses, including one who yelled at staffers who wrongly thought Borkovec, a former intravenous drug user, had overdosed when he collapsed in the doorway of his cell. The inmate's thanks for speaking up, he says, was a disciplinary chastening and seven days in lockdown.

For Anna Holland Edwards and Rachel Kennedy, two of the attorneys advocating for Borkovec, such details are as familiar as they are tragic.

"Our office has been doing jail-death cases for a number of years," notes Holland Edwards, referencing matters such as a 2022 filing over the demise of Weld County arrestee Amy Cross, "and the similarities are often the hardest to see unfold over and over again. Once again, this was a vulnerable person in the hands of the state begging for help, and the people charged with caring for him purposefully ignoring what they're being told until they die."

Nonetheless, adds Kennedy, "the prolonged and painful suffering and death of a 22-year-old from an entirely preventable bacterial infection is particularly cruel."

There is no shortage of defendants named in the lawsuit: Thirteen men and women are named individually, along with the City and County of Broomfield and the community's chief of police, Enea Hempelmann, plus Boulder's Board of County Commissioners and Sheriff Curtis Johnson. Also singled out is Oklahoma City's Turn Key Health Clinics, which contracts with Broomfield to address the medical needs of inmates, and Maryland's Maxim Healthcare Staffing Services, provider of nurses at the Boulder jail. (Turn Key is also a defendant in the Amy Cross suit.)

According to his record, Borkovec was not exactly a high-level felon. He was arrested on September 29, 2022, at a Walgreens in Broomfield and transported to Broomfield's jail for failing to appear for a court date; most of his prior offenses appear to have involved identity theft and other low-level crimes. But three days earlier, he'd been at another institution: Good Samaritan Hospital in Lafayette, where he was rushed to the emergency room after experiencing abdominal pain and persistent vomiting. While there, he was given a blood test that indicated he likely had a serious bacterial infection.

The suit states that a summary of Borkovec's exam was received by Turn Key nurses shortly after his booking, but the infection wasn't addressed. Despite an elevated pulse rate that indicated that his body was at risk of losing its fight against the bacteria, he was only put on an opiate withdrawal protocol. Moreover, a scheduled follow-up blood test was postponed before his transfer to the Boulder jail on October 6; the suit accuses a nurse of inaccurately charting that it had been completed.

As such, members of the medical crew in Boulder didn't know about the infection — but they had plenty of information that Borkovec was doing poorly, according to the lawsuit. He repeatedly sent messages known by the slang term "kites" to let them know about significant symptoms, including sore teeth leading to migraines. But the lawsuit states that his pleas tended to either be dismissed out of hand for technical reasons or placated by, for example, COVID tests (they came back negative) or a prescription for Tylenol.

Many of these edicts were delivered by nurses rather than physicians. That's typical, Kennedy allows. "The reality," she says, "is that in many jails, and particularly in Boulder, nurses act outside their scope of practice and make decisions that should be escalated up to a doctor."

To Holland Edwards, nurses in these situations are incentivized to reject most entreaties from inmates as a way of saving money. In her view, "the nurses are there as the front line to prevent access to care, as opposed to a way to get care."

She feels that there is "a special bias against drug users. I think they're biased against inmates to start, but that's especially true of people with drug issues or mental health issues. And IV drug users and meth users are at the bottom of the barrel of esteem. It's a convenient excuse for people who have to live with their conduct after it's over to disregard the humanity of the people in front of them."

As October bled into November, Borkovec's decline became precipitous, the lawsuit details. He was too weak to work and spent most of his days spitting up blood. He was also unable to eat, causing him to lose a dangerous amount of weight, and had trouble breathing. One nurse's solution to the latter was to give Borkovec an inhaler — and when he collapsed on November 3, the responders ordered Narcan, a medication administered to prevent overdoses. Neither was effective against Borkovec's infection, which soon killed him.

This sequence of events is hardly unique. Indeed, a sizable chunk of the complaint is filled with accounts of other lawsuits against Turn Key, many of which the company has resolved by way of confidential settlements — including a $3 million price tag for Turn Key in a case that concluded earlier this month. Their inclusion is a pointed attack on what Holland Edwards sees as a cynical calculus that places profits above human lives.

"Private correctional companies have been operating under the assumption that they can settle away their misconduct as the price of doing business because people don't care about inmates," she says. "But I think recent verdicts shows that people do care."

Borkovec's great-uncle Chris hopes that proves true this time around. His comment about Avery's death states: "I have been in law enforcement for the past 28 years, where we must be held accountable for our actions. In this case, there were multiple failures by various parties who were responsible for Avery's well-being. What happened to him was utterly unacceptable. Avery was a young man who deserved to be treated with care and concern. It is my hope this matter leads to change and higher standards so another family does not have to experience this."

According to Broomfield spokesperson Rachel Haslett, the city cannot comment on the lawsuit because representatives have not been served yet.

Westword has reached out to Turn Key and Boulder County for comment about the lawsuit. See The Estate of Avery James Borkovec v. Turn Key Health Clinics, et al., and accompanying witness statements below. This article was updated to correct an error stating former Boulder County Sheriff Joe Pelle was listed in the lawsuit.

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangleLeft",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangleRight",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangleLeft",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangleRight",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "leaderboardInlineContent",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "tower",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

}

]