It had been a summertime of rain, constant and hard at times. State money was tight, federal money even more so, and deferred maintenance on municipal structures was starting to be an issue. Some officials complained that natural disaster was not only possible, but just a matter of time. The debate took the place of action, though; for years, no one did anything, because no one could agree on the problem, let alone potential solutions.

Sound familiar?

This was Colorado in 1933. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Franktown was a tiny unincorporated town back in 1933, dwarfed by Denver some 35 miles to the northwest, up Cherry Creek. While the City and County of Denver boasted a population of close to 300,000, all of Douglas County contained just over 3,000 residents. Still, Denver and Franktown had two things in common back then: Times were tight and getting tighter, and the Castlewood Dam was central to each town's future.

The dam had been a political conundrum since its construction in 1890. And on August 3, 1933, the dam burst as many feared — even expected — it would. It released more than a billion gallons of water into Cherry Creek, which saturated local farms as the flood roared to Denver, uprooting trees and structures and anything it met. The wall of water was fifteen feet high as it rushed through southeast Denver, destroying bridges over Colorado Boulevard and on Stout and Champa streets, then filling the basin of downtown. It flooded buildings and took some of them down completely. Only two people were killed, which everyone said was a miracle.

But the damage overall was massive and unprecedented, and it changed both the physical and philosophical future of Denver.

The Castlewood Dream

By the time it failed, the Castlewood Dam had been in precarious operation for 43 years. It was important to both the local economy and that of Denver proper, providing the necessary water for a struggling but surviving series of farms, fields and orchards. The land around Franktown was much like the plains that stretched out to the east: flat, arable and profitable.

The potential for that profit is what had brought the dam into being: The project was the concept of the Denver Water Storage Company, in partnership with Denver Land and Water, two of many hydro-pioneers that would give way in 1918 to the municipal entity still called Denver Water today. Back then, they figured that if they built it, farmers and businesses would come — and they were right. The dam itself was designed by chief engineer A.M. Welles and constructed in a rock-fill strategy composed of two freestanding walls: a straight wall on the reservoir end and a stepped wall on the other. It was built entirely by hand by over 300 men and 180 teams of horses over 11 months; when finished, it was 600 feet across, 70 feet tall, 8 feet thick at its top and 50 feet deep at its base.

“From the moment the dam began impounding any significant amount of water, countless reports were filed by a number of government and private agencies ensuring the dam’s safety, but the dam’s stability was publicly debated continuously until the day it failed," wrote University of Colorado Denver geology professor Casey D. Allen in "Denver's Forgotten Flood," a 2014 article with lead author Kaelin Groom of Arizona State University.

Several local newspapers found the Castlewood Dam’s safety concerns to be worthy of headlines, including the Rocky Mountain News, the Denver Republican and the Denver Post. On May 1, 1900, Welles penned a letter to the Post defending his work on the dam and calling any criticism or doomsaying “prattle of sensationalism, incompetence, and vindictiveness.” In modern nomenclature: fake news. “The Castlewood dam will never, in the life of any person now living, or in generations to come, break to an extent that will do any great damage either to itself or others from the volume of water impounded,” Welles wrote, “and never in all time to the city of Denver.”

It was hardly a prescient claim. Both before and after Welles’s assurances of safety, literal cracks were already appearing in the dam despite numerous attempts to rectify their threats. Even after a complete draining of the reservoir for repairs, the seeping water continued unabated.

Economic Pressures and Expansion

Meanwhile, investment in the area thrived. Once early Colorado settler Rufus “Potato” Clark sold off the 15,000 acres that he’d bought as part of the Denver Water Storage Company venture, a new investment plan was devised by the newly formed Denver Sugar, Land, and Irrigation Company in 1902. The company advertised extensively throughout American cities back east, working to draw men and their families west. The idea, according to Castlewood Canyon State Park’s "The Night the Dam Gave Way,” was “to build a sugar factory and sell small farms to future settlers who would have a ready market for sugar beets.” To do that, though, they needed men to work the land. A 1903 pamphlet distributed in urban areas all over the Eastern Seaboard promised annual profits of thousands of dollars for only six months' farming work on ten acres of land. It promised a place to claim a stake, for three specific reasons: for the sake of a man, for his wife, and for his children.

The pamphlet included strong lures indicative of their era:

There is no life so healthful, so independent, so care-free as that of a farmer raising high-priced products near a big city…He is his own master, working for himself, and getting for himself the fruit of his labor, intelligence, thrift, and forethought.

What man working for wages or an ordinary salary can lay up enough to provide for his wife in case he is taken by death? But if he leaves a small farm, well fruited, he leaves at once a permanent home and a permanent income. And while both live, a man can give his wife greater comfort, greater health, greater enjoyment of life, more luxuries, more freedom than he possibly can in any town or mining camp.

American history shows that the boy who is brought up in the country has 50 percent better chances of success than the

city boy. On a small farm, near a city, your boy can get as good school facilities as though he lived in the most thickly settled town. He gets an open-air life. He has employment for his vacation hours. There is a greater chance for recreation–innocent fun. There is an outlet for his exuberance without doing harm. He is secure from temptation and degrading influences. And the farmer’s daughters – are they not the very highest types of American girlhood and womanhood?

Despite all these promises and platitudes, the idea didn’t survive long enough to become “well-fruited.” The Franktown sugar factory fell through without ever breaking ground, and the whole idea was more or less abandoned. Another investor group would come to cultivate cherry trees and offered small sections of land for “retirement farming,” but this scheme failed, too. After a while, the water rights fell into a legal tangle of who owned what and languished until 1923, when small farmers began to settle the area independently, growing alfalfa and other crops. The dam and its surrounding area would finally become a home for some...for a while.

“Nature’s Paradise”

During the 1920s and early ’30s, Castlewood Dam was a popular recreational area for Denver families, decades before it would finally become a Colorado State Park in 1964. The park has collected memories of those old enough and lucky enough to remember the place before the flood changed everything. Mildred Sas of Broomfield recalls the area being rife with wildlife, from porcupines to the mountain lions that hunted them. Rattlesnakes would sun themselves on the east side of the reservoir rocks in the afternoon, and a pair of large eagles nested in the crook of a pine tree that had been struck by lightning. “I can’t describe the beauty of that canyon,” Sas says.

Harvey B. Cochran visited Castlewood Dam when he was a student at Denver’s East High, and he and his friends were obsessed with the lore of the frontier — which had closed just forty years earlier. They haunted the pawn shops on Larimer Street, which by the early 1930s was becoming Denver’s skid row, and bought Colt six-shooters for $10 apiece. Cochran recalls practicing shooting on “the edge of town,” then somewhere just beyond East 26th Avenue and Monaco Parkway. In seeking to re-create the Old West of the tales they’d read in dime novels and pulp magazines, they’d head to Castlewood Dam and shoot their pistols to see how far the bullets would travel, judging distance by the location of the splash. Cochran says his .45 could shoot nearly halfway across the water.

The Dam Breaks

In the summer of 1933, the rains came. For days, the Franktown area experienced intermittent showers; by August 3, the ground was saturated. So when a cloudburst deluged the Cherry Creek basin with over eight inches of rainfall within a matter of a few hours, the writing was already on the dam's crumbling wall.

Hugh Paine was the dam's caretaker; he lived on site with his wife. On August 4, the day after the dam burst, he wrote an article for the Rocky Mountain News about the disaster. “We had thought for years of what would happen if the dam should go,” Paine wrote, “but it had withstood such terrific buffeting in previous years that we felt it was safe. Still — we didn’t know.” Shortly after retiring on August 3, the Paines heard a threatening rumble, and went to the window to see the dam “breaking up under a wall of water that was pouring over its top,” he recounted. Paine attempted to telephone a warning to everyone downstream, but his lines were already dead. He and a neighbor traveled — very slowly and cautiously — for twelve miles before reaching the Castle Rock telephone exchange, where they were able to sound the warning. “We escaped disaster a dozen times,” Paine recalled. “But we made it…and that was all that mattered.”

Paine's efforts to find a working phone — and the availability of that still relatively new technology — are credited with saving countless lives in the flood. Information was able to stay ahead of the floodwaters as farmers were told to move their livestock and machinery and everyone was advised to move to higher ground.

The Flood and Denver

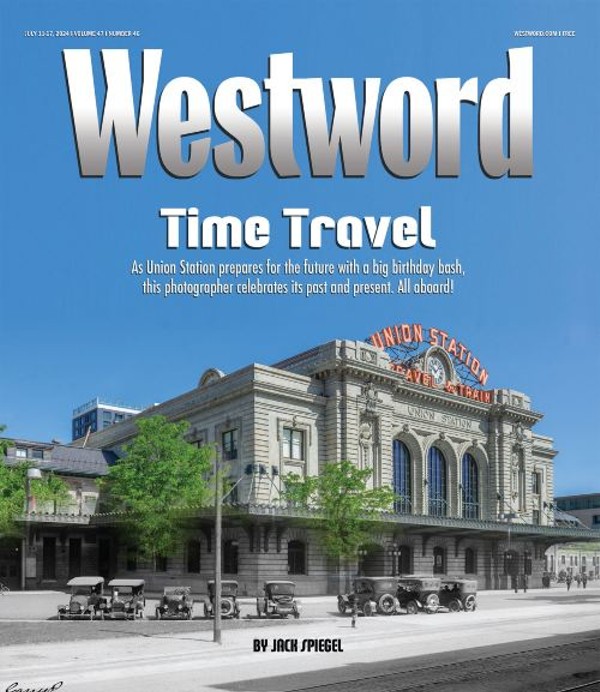

As the wall of water came into downtown Denver, carrying debris with it, the curious came out to view the destruction. Three feet of water stood in Union Station, whose lower levels and baggage subways were entirely filled with muck. The Sunken Gardens in front of West High School were underwater, the meticulously maintained flowerbeds drowned, the twinkling night lights extinguished, and the Moorish pavilion that served as its centerpiece damaged to such a degree that it later had to be demolished. Almost no bridges survived; only the larger viaducts connected the two sections of the city.

One of the worst scenes was where the bridge over Cherry Creek had collapsed at Colorado Boulevard, then the eastern border of Denver. Teen George Madsen and some friends had heard that the bridge was destroyed, and they rode their bikes over. What they saw wasn’t just destruction, but tragedy: The debris from the bridge had combined with uprooted trees, driftwood, old lumber, everything that had tried to fight the current but failed, including a number of animals: Calves, chickens, a horse, some sheep, a dog, ducks and others were crushed up against the remains of the bridge, still living but trapped. “[They] were trying desperately to escape the force of flood waters,” recalls Madsen in "The Night the Dam Gave Way." “But to no avail. Each time an animal tried to get away from the debris lodged against the bridge, the worse became its predicament. It was hopeless.” Authorities were forced to put the animals down from a distance using their sidearms. Madsen says that it was “the only humane action that could have been taken under [the] awful circumstances,” and that witnessing it left him “deeply saddened.”

Water was everywhere — “hubcap-deep” in lower downtown, much worse in other areas. The Campbell-Sell Bakery on 12th and Curtis streets (now part of the Auraria campus) had managed to stuff its trucks full of baked goods and ingredients and drive them to safety, but lost 100 pounds of raisins stored in the basement, where they plumped up with filthy drainwater. The Cambridge Dairy at Steele and Exposition was sundered by the water and caved in on itself. Cars trapped in high-water marks had to be towed back to their owners’ homes — assuming they were still livable — full of mud and debris.

In all, the reported damage caused by the flood was $1.7 million, which in today’s dollars would be nearly $40 million. And that tally was definitely low: This was before widespread and dependable home and car insurance, which wouldn’t be regulated until the Social Security Act of 1935.

Amazingly, only two people lost their lives. They were 83-year-old Tom Casey, who drowned while attempting to salvage what he could from his Denver home and got caught in the rush of water; and 24-year-old Bertha Catlin, a visitor from Page, Kansas, who died near Franktown when the horse she’d ridden to view the flood damage threw her into the water.

The Aftermath

Metro Denver still shows the lingering effects of the 1933 flood.

The immediate area around what had been Castlewood Dam is now a day-use state park with several hiking trails, rock-climbing areas and picnic facilities. Visitors can still see the remnants of the dam, along with a visitor’s center that tells its history. According to the geological reporting of Groom and Allen in “Denver’s Forgotten Flood,” the landscape was changed dramatically. The flood “scoured the sides of the canyon” by up to 36 feet and deepened it drastically, in some places up to nearly 30 feet. They estimate that almost 1.6 million cubic feet of rock and other material was displaced by the flood itself; in the years since, another 70,000 cubic feet have been moved because of the floodpath.

Denver, too, still shows markers of the flood. The Sunken Gardens lost its central pavilion, though its foundation remains. Bridges had to be rebuilt, as did the lives of those who lost homes, cars, livelihoods. The Cherry Creek Dam became a priority, with construction starting in 1946.

Most of all, the 1933 flood changed the way Denver deals with water-related risks, even to this day. In addition to building new, better dams — Chatfield came after the 1965 flood — governments emphasize preparedness. The Federal Emergency Management Agency recently created an interactive app called Floodwalk, centered in Confluence Park, to visually illustrate the dangers inherent in flood conditions. “All of the people in Colorado and along the South Platte River watershed are at some risk of flooding,” warns FEMA's Tony Mendes, “whether you live near the water or far away."

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "leaderboardInlineContent",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "tower",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

}

]