On election night, while Governor-elect Jared Polis and others celebrated the party’s historic wins at the Denver Westin, thousands of Floridians left homeless by Hurricane Michael were still sleeping in tents and shelters. Two days later, the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in modern American history ignited near Paradise, California.

And as triumphant Democrats spent the holiday season anticipating their tightest grip on the reins of state government in eighty years, the world’s scientists were delivering an increasingly urgent series of warnings about the consequences of failing to address the global climate crisis. “We’re out of time,” says Mike MacFerrin, a University of Colorado Boulder glaciologist and climate activist. “The time for half-measures is over. We’re at an inflection point, globally. People are starting to feel the impacts. It’s no longer abstract; it’s no longer confined to a computer model.”

Swept into power by the blue wave, Colorado Democrats are quick to draw a contrast between themselves and Republicans on the issue of climate change. They say that they accept what scientists have been telling the world for over thirty years: Human activity is releasing unsustainable quantities of heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere, causing our planet to warm to the point of widespread ecological upheaval and collapse. They say they’re ready to act to stop it.

“There’s nothing less at stake than our future itself,” Polis told a gathering of Colorado Sierra Club members last year. “You may not like politics. You may think it’s just a bunch of people arguing all the time. You may not trust any of them. But at the end of the day, there is too much at stake to ignore it. The outcome of our elections will determine the outcome for our planet.”

The outcome of November’s election was unambiguous: Polis defeated GOP rival Walker Stapleton by nearly eleven points, as Democrats booted Republicans from three other statewide offices and gained full control of the Colorado Legislature for the first time in four years. As for the planet, however, it remains to be seen whether Polis and other top Democrats have grasped the full implications of the international scientific community’s warnings — its conclusion, for instance, that in order to avoid catastrophic levels of warming, Colorado and the world at large must cut carbon emissions nearly in half by 2030.

In conversations with more than a dozen scientists, activists, lawmakers, state regulators and others, a clear picture emerges: Despite encouraging developments on several fronts, there remains a significant gap between the policy agenda that Democrats have put forward in this state and the scale and urgency of action that the climate crisis requires. Like much of the rest of the world, Colorado is nowhere near on track to achieve the overall emissions cuts that scientists say are necessary over the next decade and beyond. And every day that passes without action only makes the task ahead that much more difficult.“The outcome of our elections will determine the outcome for our planet.”

tweet this

Experts stress that the barriers to rapid decarbonization are not technological, as nearly all of the technologies needed to make a carbon-zero world possible already exist. Nor are they economic, as the costs of doing nothing far outweigh the costs of effective mitigation. If the world fails to do what’s necessary to stop climate change, the failure will be political. Democrats have promised that they won’t fail in Colorado; now comes the hard work of fulfilling that promise.

“We still have a ways to go,” says Jeremy Nichols, climate and energy program director at the environmental group WildEarth Guardians. “We have some work to do, for sure. But the winds have changed here in Colorado, and they’re definitely going to be felt, not only by our neighbors, but other states beyond, and I think it’s going to reach all the way to D.C. People are excited right now, and they’re rising up. They’re realizing we really have no choice.”

Global Alarm Bells

“Rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society.”That’s what the world’s top climate authority says is necessary to limit warming to an average global temperature rise of 1.5 degrees Celsius. Exceeding that limit, warned the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in October, will put hundreds of millions of people around the world at greater risk of famine, disease, extreme poverty and forced migration.

Beyond 2ºC of warming, the chances of widespread ecological devastation and human suffering begin to increase exponentially. Entire regions of the world would be remade by droughts, floods, heat waves and rising sea levels. Mass displacement, economic depression and political destabilization, the IPCC’s report warns, would create a world that “is no longer recognizable.”

Current projections show that the climate is on track to blow through both limits and warm by more than 3ºC by 2100.

The IPCC’s findings were echoed a month later by the Fourth National Climate Assessment, a congressionally mandated report prepared by thirteen U.S. government agencies. In virtually every corner of the country, the assessment found, Americans are already starting to feel the effects of climate change — including in Colorado and the rest of the West, where the risks of severe drought and wildfires are steadily increasing owing to warmer temperatures.

Despite these warnings, the Republican-led federal government has spent the past two years reversing what little climate progress had been made at the national and international levels. President Donald Trump’s administration has slashed clean-air protections, suppressed the work of its own scientists and opened up millions of acres of public lands in the West for new drilling. Later this year, it will complete its withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, the landmark decarbonization treaty signed by nearly 200 countries in 2015.

This backsliding by the world’s second-largest carbon polluter is, in part, what led the U.N. Environment Program to stress the importance of state-level climate mitigation in a report it issued in November. “More actors must engage in climate action,” said the program’s annual Emissions Gap Report. Subnational actors like state and city governments, it argued, “can play a key role in building government confidence in implementing climate policies, and they can signal and push for greater ambition.”

State representative Chris Hansen, an energy consultant who represents east Denver in the legislature, agrees. “States are going to have to lead, because of the abdication in D.C. by the Trump administration,” he says. “Colorado has been a leader, but I think we’ve fallen behind, in some ways, from that leadership position that we held for many years. It’s time for us to be more assertive on climate change and clean-energy policy.”

In 2017, Colorado became one of sixteen states to join the U.S. Climate Alliance, whose members have committed to meeting the emissions goals outlined in the Paris Agreement. In pursuit of those goals, Governor John Hickenlooper signed an executive order mandating a 26 percent cut to statewide carbon emissions by 2025. Establishing a more ambitious target is likely to be a priority for Colorado climate activists this year. The country’s most aggressive state-level emissions mandate was passed by California’s legislature in 2017; it requires an economy-wide emissions cut of 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030, roughly in line with what the IPCC says is necessary to avoid 1.5°C of warming.

But top-down emissions mandates merely set goals; it takes focused policy intervention to meet those goals. The world’s leading climate scientists aren’t shy or equivocal about what those policies have to accomplish: “rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society.” The question is whether political leaders around the globe are willing to do what’s necessary to make those changes.

“There are very real manifestations of the climate crisis happening now that are impacting people in real ways,” says Taylor McKinnon, a climate activist with the Arizona-based Center for Biological Diversity. “So I think that lends urgency to action by the Polis administration. What we have right now are campaign promises that need to be translated into real policy action.”

The 60-Million-Ton Question

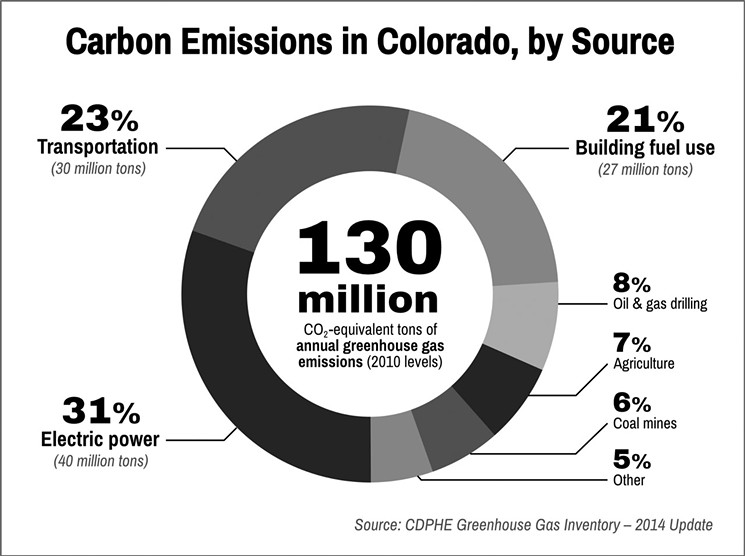

It’s impossible to precisely measure the vast quantities of invisible, heat-trapping gases that are, at any given moment, being released into the atmosphere by Colorado’s cars, power plants, furnaces, factories and feedlots. But scientific models give us a pretty good idea.The state’s most recent Greenhouse Gas Inventory, issued in 2014 by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, estimated that the state emitted 130 million CO2-equivalent tons of greenhouse gases in 2010, and projected that total to rise slightly, to 134 million tons, by 2020. (According to the CDPHE, an updated report is expected to be completed in the first half of 2019.)

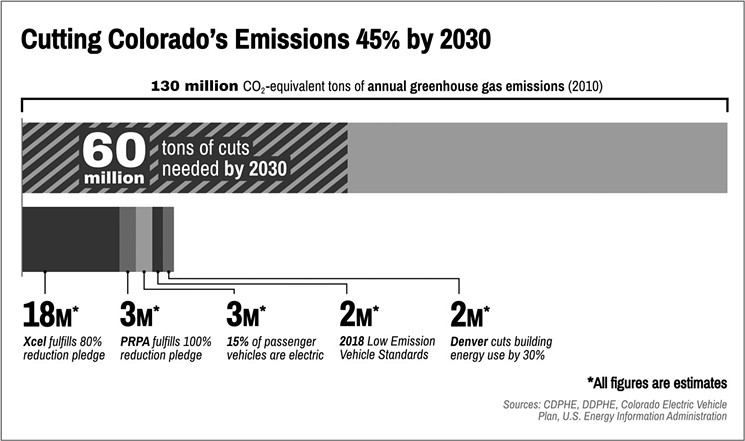

That means that in order to do its part to avoid global catastrophe, Colorado has just eleven years to eliminate roughly 60 million CO2-equivalent tons from its current annual emission levels. To put the scale of that challenge in perspective, the state’s newly approved low emissions vehicle standards — hailed by Democrats as a major victory and assailed by Republicans as an intolerable overreach — will reduce emissions by just 2 million tons annually by 2030, according to CDPHE estimates.

Where will the other 58 million tons of cuts come from? That’s the question that Polis and Democrats in the legislature will soon have to answer if they want to make good on their promises to take climate change seriously. Polis made green energy goals a centerpiece of his gubernatorial campaign, pledging to put Colorado on a path toward 100 percent renewable electricity by 2040.

Such a goal looks achievable: With wind and solar power cheaper than ever, energy providers are ramping up efforts to retire old, heavy-emitting coal plants and investing aggressively in renewables to replace them. Xcel Energy, Colorado’s largest electric utility, announced in December that it plans to reduce emissions from electricity generation by 80 percent by 2030 and achieve 100 percent carbon-zero electricity by 2050.

“There is a difference between clean energy and clean electricity.”

tweet this

Appearing alongside Xcel executives at a press conference announcing the pledge, Polis vowed to support policies that would accelerate the transition and encourage other utilities to follow suit. That could be accomplished, in part, by “making it easier to site renewable-energy projects on public land [and] working for a pathway for rural electric co-ops to be able to embrace renewable energy,” he said.

Shortly after Xcel’s announcement, the Platte River Power Authority, which provides electricity to Fort Collins, Loveland, Longmont and Estes Park, one-upped the utility with a pledge of its own: to achieve 100 percent carbon-zero electricity by 2030.

As positive as these developments may be, however, electricity generation accounts for only 31 percent of Colorado’s annual carbon emissions, according to the CDPHE’s 2014 report. Even if other electric utilities follow Xcel’s lead and achieve a sector-wide 80 percent emissions cut by 2030 — which seems far from likely, given the coal-heavy portfolios of smaller providers like Westminster-based Tri-State — the carbon savings would amount to roughly 32 million tons. That would leave another 26 million tons in cuts that still need to be made elsewhere.

Most of those cuts will have to come from some of the most overlooked areas of climate and energy policy — and some of the least politically palatable. Experts worry that even as momentum builds for popular, well-understood goals like 100 percent renewable electric power, other, major sources of emissions are at risk of being ignored.

“There is a lot of public confusion about clean energy,” says Laurent Meillon, CEO of Castle Rock-based Capitol Solar Energy and a renewable-energy advocate. “There is a difference between clean energy and clean electricity.”

Over 20 percent of Colorado’s carbon emissions come from building fuel use: furnaces, boilers, water heaters, ovens, stoves and more, the vast majority of which are powered by natural gas. At roughly 27 million tons annually, buildings are Colorado’s third-largest source of emissions, after electricity generation and transportation. Despite this enormous carbon footprint, however, building emissions have been the object of far less attention, and far less regulatory and legislative scrutiny, than the electric and transportation sectors.

The technology exists to achieve deep cuts in emissions from building fuel use over the next decade, experts say. Buildings can be constructed or retrofitted to be more energy-efficient; gas-powered heating systems can be electrified or converted to use clean-heating technologies like solar thermal. But public policy to mandate or incentivize such a transition has lagged far behind other green-energy programs.

“Ninety-nine percent of the focus is on electric energy,” Meillon says. “There’s been a dearth of planning or programs on sustainable heating in Colorado.”

“There’s been a dearth of planning or programs on sustainable heating in Colorado.”

tweet this

A report released last year by the Clean Energy States Alliance found that fourteen states now include clean-heating technology in their renewable portfolio standards, the regulatory tool by which most states mandate certain levels of green energy production. Colorado isn’t one of them. That needs to change, Meillon says, adding that the state also needs to push the Public Utilities Commission, the agency that oversees much of Colorado’s energy infrastructure, to incentivize clean and efficient heating alongside electricity. The PUC is up for a periodic sunset review in the legislature this session, giving lawmakers the opportunity to ensure such reforms are enacted.

“Part of it is really being aggressive on the efficiency side so you burn less in the first place,” says Hansen. “But long-term, it’s going to take a massive reinvestment in the heating sector. That’s going to have to be part of our overall strategy. It’s not enough just to look at electricity and transport; we have to push electrification into the heating sector as well.”

Hansen, an Oxford Ph.D. who wrote his dissertation on electricity reform in India, views the heating sector as perhaps the most difficult source of carbon emissions to tackle. “You’re talking about a huge capital reinvestment,” he explains. “If you add up the value of everybody’s furnaces, and the systems that we have in place in our homes, in our offices, in our apartments — it’s multiple trillions of dollars across the U.S.”

The Road to Electrification

Over 30 million tons of carbon dioxide are emitted annually by Colorado’s cars, trucks, aircraft and other fossil-fuel-powered vehicles, and estimates show that figure inching steadily upward amid a population boom and a growing economy. The chances of making deep cuts into those emissions over the next decade appear slim.

In the long run, the best way to cut transportation emissions is through a mass transition to electric vehicles (EVs) and transit networks, particularly as the energy powering the electric grid becomes cleaner and cleaner. But a variety of factors are holding that transition back. “Lack of infrastructure is clearly one of the biggest barriers,” says Christian Williss, director of transportation fuels and technology at the Colorado Energy Office. “Focusing our efforts on expanding infrastructure and charging options across the state are critical.”

Though costs are falling fast, a lack of affordability has also hindered EV adoption — as has a simple lack of public awareness. “The majority of people don’t really know that EVs are out there,” he says. “We see a desperate need for education and awareness — things like ride-and-drives, educating salespeople, making sure that EVs are kept on dealer lots, and doing actual marketing around electric vehicles. We simply don’t see a lot of investment in marketing, TV ads, that sort of thing.”

The Colorado Electric Vehicle Plan, released by Hickenlooper’s administration last year, commits the state to a goal of 940,000 electric cars on the road by 2030, or about 15 percent of all passenger vehicles in the state. Even in this “maximum practical scenario” for EV adoption, however, the carbon savings are projected to be modest: only about 3 million tons of emissions annually, according to the report.

Colorado could decide to follow the lead of California and nine other states in adopting a zero-emissions vehicle mandate, requiring automakers to sell a certain number of electric vehicles as a percentage of their overall sales within the state. Regulators will decide whether to move forward with the ZEV rule in May.

Hansen thinks it’s time for lawmakers to act more aggressively on electric vehicles, too. “I think you’re going to see a lot of conversation this session on how to hasten the pace of electrification in transportation,” he says. “I think it’s incumbent on the legislature to put in place the right incentives for EVs, as well as to build out and support the charging infrastructure.”

Without rapid, mass electrification, significant emissions cuts in the transportation sector could be made simply by changing how Coloradans get around — in short, by encouraging fewer people to drive cars. But broad swaths of public policy in Colorado seem to be doing just the opposite. Denver’s four-year, $1.2 billion expansion of Interstate 70, championed by Hickenlooper and Mayor Michael Hancock, could ultimately raise drivership rates, which are already significantly higher than the city wants them to be. Denver’s Office of Sustainability has aimed for less than 60 percent of all commutes to be made in single-occupant vehicles by the end of 2020, with a goal of 50 percent by 2030 — but over the past five years, that figure has barely budged from around 70 percent.

But if progress on transportation and buildings seems slow or stalled, there’s one sector in which climate activists say Colorado is moving backwards.

Demand and Supply

Colorado’s multibillion-dollar oil and gas industry, the fourth-largest source of greenhouse emissions, packs a one-two climate-warming punch. Its drill sites, wells, tanks and pipelines are themselves major, direct emitters of hydrocarbons like methane. And the extracted fossil fuels, of course, are sent downstream in the supply chain to be burned in Colorado or elsewhere and released into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide.

Exactly how much methane leaks out during oil and gas production is a matter of considerable debate. In 2014, Colorado enacted a set of rules requiring operators to find and fix leaks on a more regular basis. But those leaks still numbered over 17,000 in 2017, according to state data, and even small amounts of methane can be devastating for the climate. A major study published last year in the journal Science estimated the industry’s leak rate at 2.3 percent, enough to offset most of the oft-touted climate benefits of natural gas compared to coal.

In any case, the indirect effects of pumping massive quantities of fossil fuels into the nation’s energy markets are beyond doubt. As a matter of simple thermodynamics, there is no possible future in which climate change is successfully mitigated and Colorado’s oil and gas industry is still producing at anywhere close to its current levels. That’s a reality with which the state’s political establishment, Republican and Democrat alike, has had trouble coming to terms.

“The industry has become so entrenched in state politics, on both sides of the aisle,” says Nichols. “The Democratic Party has struggled to address it, and instead has been willing to just go along with it because of how much power they exert within the party.”

Higher efficiency standards, incentives for wind and solar power, and electric vehicle adoption all seek to reduce demand for oil, gas and coal. To date, these demand-side policies have accounted for the vast majority of climate action by governments in the U.S. and around the world. In the view of many activists, this means policymakers are trying to tackle climate change with one arm tied behind their backs.

“Supply side is the next frontier of climate policy,” says McKinnon. “Regulating tailpipes and smokestacks isn’t enough.”

Studies have shown that the planet’s “proved” fossil-fuel reserves — that is, the oil and gas waiting to be extracted in fields that have already been developed — are already more than enough to push the climate past the 2°C warming limit, if they are extracted and burned. Yet Colorado is approving thousands of new wells every year, with record numbers of drilling permits waiting to be rubber-stamped by state regulators. On average, Colorado drillers are pumping a staggering five times more oil per month than they were when Hickenlooper took office eight years ago.

“Phasing out new drilling and leasing is a key part of any serious climate platform moving forward,” McKinnon says. “New leasing and drilling needs to end. It should have ended years ago.”

The math is inexorable; even Hickenlooper, a geologist who’s been a staunch industry ally, conceded in a 2017 interview with Colorado Public Radio that fossil fuels will “at some point” have to be left in the ground. Polis spokeswoman Mara Sheldon declines to discuss any plan Polis might introduce as governor until after his policy team is in place; in the meantime, she points to statements on climate change on his House website. “Simply put,” it says, “Colorado has a vested stake in the health of our world’s climate.”

Activists are hopeful that the Polis administration could begin to slow the runaway growth of drilling along the Front Range, both by supporting strengthened protections in the legislature and by appointing stronger climate and environmental advocates to state agencies. But that will mean taking on an industry with deep pockets and enormous influence within Colorado’s halls of power. “Constraining and phasing out fossil-fuel supply ultimately puts [politicians] in the crosshairs of a very powerful oil and gas lobby,” says McKinnon. “Climate leadership requires taking the side of the climate’s future instead of that lobby. We’ve not seen that done in the past, and that needs to be done now.”

For organizers and activists who helped deliver big wins for Polis and other Democrats in November, addressing climate change and the environmental effects of oil and gas drilling is a top priority. According to Katie Farnan of Indivisible Front Range Resistance, many of her fellow activists in Broomfield, Thornton and other communities that have been directly impacted by fracking are ready to see the new governor and the legislature confront those issues aggressively.

“We’re looking for leaders who are going to take bold action,” Farnan says. “We can’t just have half-measures, and we can’t just have commitments that look out into the future, to 2030, 2040, 2060. That’s not going to work. It needs to be a shortened timeline.”

“Continued, Decisive Action on Many Fronts”

Often lost in the debate over future climate impacts is the fact that Colorado has already warmed significantly over the last thirty years; average temperatures statewide have risen by more than 2ºF, outpacing the global average. This warming, scientists say, is the primary culprit behind declining stream flows in the Colorado River Basin, the water source for nearly 40 million people across the Southwest. In a 2018 paper, scientists at the Colorado River Research Group advised against using the term “drought” to describe what is happening in Colorado and other Western states. “Drought” implies a temporary condition. A better word for what we’re experiencing is “aridification.”

“Moving forward means abandoning the mindset that current changes to climatic and hydrologic regimes are a temporary phenomenon,” the paper says. “We are not likely to ever return to normal conditions; that opportunity has passed.” Our choice now, the authors write, is between stabilizing water supplies at a lower but still sustainable level, or watching as the aridification process continues and likely accelerates: “Words such as drought and normal no longer serve us well, as we are no longer in a waiting game; we are now in a period that demands continued, decisive action on many fronts.”

These dramatic atmospheric and ecological shifts are happening all around the world. Unfortunately, says CU’s MacFerrin, whose research focuses on the Greenland ice sheet, these are exciting times to be a glaciologist. “There are a lot of things that we’re realizing ice sheets can do very quickly,” he explains. “We go to Greenland, and I see these changes on vast, continental scales. You look around and you’re like, ‘Holy shit, this is big.’ But I can’t absorb that all the time. I would be a depressed mess all the time if I just did nothing but think about the consequences of it.”

There are signs that the warnings scientists have been issuing for the past three decades are finally starting to sink in with policymakers. At the federal level, a surge in climate activism has led to protests and sit-ins in the halls of Congress as Democrats prepare to take control of the House of Representatives for the first time since 2010. Led by youth activist group the Sunrise Movement and newly elected progressives such as Colorado’s own Joe Neguse, the push for a “Green New Deal,” a program to massively expand federal investment in decarbonization and green jobs, has picked up endorsements from influential Democrats and several likely 2020 presidential nominees.

“We are not likely to ever return to normal conditions; that opportunity has passed.”

tweet this

As Polis and the legislature’s new Democratic majority prepare to be sworn in, Colorado activists hope to bring that movement to the steps of the Capitol. But for now, a 100 percent renewable electric grid by 2040 is the only major decarbonization goal that the governor-elect has endorsed. (Citing ongoing work by the transition’s policy committees, the incoming Polis administration declined to comment on specific plans for reducing emissions from other sectors.)

Chris Hansen is hopeful that Colorado and the world can achieve the required levels of decarbonization over the next decade and beyond. This session, he plans to introduce bills to accelerate the retirement of old coal plants and further encourage community solar projects. At a certain point, he says, the growth of transformational clean-energy technologies will become exponential.

“It’s an aggressive goal, to get a 45 percent reduction by 2030,” Hansen acknowledges. “But I think it’s very feasible, based on current technology and near-term technology that we know is in the pipeline. It’s not a linear change. We’re going to see a very rapid increase in electric vehicles, for example.

“Just like wind and solar accelerated as they became cheaper alternatives to natural gas and coal,” he adds, “I think something similar is going to happen in the transport sector, as these technologies improve and costs continue to fall. We’re kind of at that take-off moment.”

Other activists are looking to the near future with a mix of hopefulness, skepticism and resolve. The green movement has seen false dawns before. But with the effects of a rapidly changing climate already being felt as carbon emissions continue to rise, the stakes have never been higher.

“Politicians tend to target short-term things that the electorate can see and benefit from so they can get re-elected,” Meillon points out. “We’re dealing with a long-term and global problem, and that often does not bode well with our institutions and the way people think. I think there’s a lack of political will — but nonetheless, it’s increasing.”

“We’re starting out with a rosy picture, because we elected a lot of great people,” says Farnan. “But these things can go south, and we’re not going to let that happen.”

Farnan and other Indivisible activists are planning to hold monthly lobbying days at the Capitol, pressuring lawmakers to act on climate, renewable energy and other issues. They’ve been energized by the efforts of the Sunrise Movement and other climate activists in Washington. Carrying that energy forward may make all the difference, for Colorado and for the world.

“I’m hoping that voters stay involved and make them follow through on their promises,” MacFerrin says. “Because that’s been one of the Democratic Party’s big downfalls. They pay lip service, but if they come up against any opposition, it becomes a back-burner issue that doesn’t really get handled; it’s just kicking the can down the line, again and again and again. And we’re out of time.”