Regalado and his wife, Kaitlyn, allegedly raised $3.2 million from 300 investors, selling them a "practically worthless" cryptocurrency called INDXcoin, according to a civil complaint. While they used Bible quotes and promises of blessings to sell the coin, the couple pocketed $1.3 million and spent the money on a Range Rover, home renovations, vacations, luxury handbags and cosmetic dentistry, the complaint charges.

In a video statement posted on January 19, Regalado admitted to taking $1.3 million, claiming the bulk of the money went to the IRS, but "the Lord told us to" spend hundreds of thousands of dollars renovating their home.

He also blamed God for the idea of creating the cryptocurrency in the first place: "The hand of God is on this project. ... What if I get this wrong? What if it doesn't happen? It's not on me, it's on Him," Regalado said in a YouTube live launching INDXcoin in April 2023.

In the complaint, Colorado Securities Commissioner Tung Chan said Regalado took advantage of the Christian community and "peddled outlandish promises of wealth to them." Now facing civil fraud charges, Regalado says he's still hopeful that “God is going to work a miracle in the financial sector" to get his investors their money back. That miracle didn't come at a January 29 hearing before Denver District Court Judge David Goldberg; Eli and Kaitlyn Regalado were no-shows. But they've already been banned from selling their cryptocurrency in Colorado, and are prohibited from accessing their ill-gotten gains.

While his Godly grift is the latest to catch the nation's attention, Regalado isn't the first scammer to put Colorado on the map. In fact, the state has a long history of crooks swindling their fellow Coloradans.

Here's a look at some of the most infamous con artists to ever bilk the Centennial State:

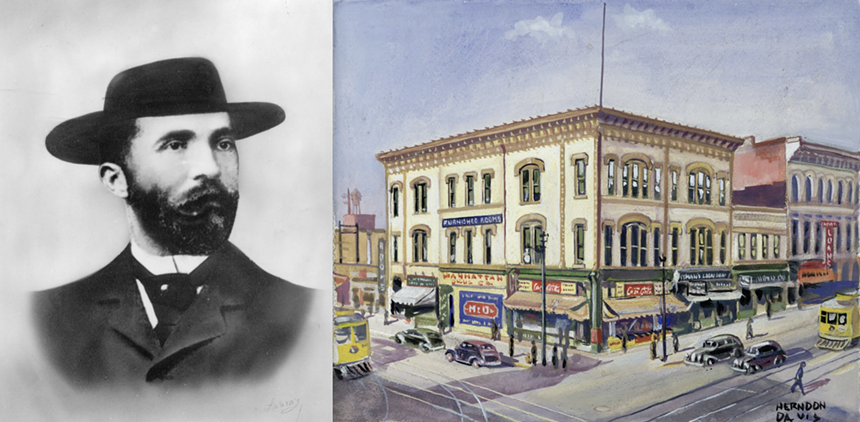

Soapy Smith, 1879-1894

The notorious "king of the frontier con men" spent years running the criminal underworlds of Denver, Leadville and Creede. Jefferson Randolph “Soapy” Smith and his gang came to Denver in 1879 and quickly developed an empire, orchestrating fake stock exchanges, lottery offices and diamond auctions — in addition to small cons like his namesake soap scam, where he'd sell soap bars for the chance of selecting one with a hundred-dollar bill inside, though the winning bar would always go to one of his gang members.

Soapy Smith and his Denver office at the corner of Larimer and 17th Streets.

Denver Public Library Special Collections

Smith's reign ended shortly after Davis Waite was elected governor in 1893, vowing to clean up Denver's organized crime. Waite demanded the resignation of police and fire boardmembers he believed were corrupt. Refusing, the boardmembers and their supporters barricaded themselves inside City Hall for ten days. Waite called the Colorado National Guard and federal troops to force them out, pointing cannons at City Hall. In turn, Smith helped fund a police force to fight the governor's troops and was called a "colonel" in the conflict, known as the Denver City Hall War of 1894.

In the end, the standoff ended with an agreement to submit the case to the Colorado Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of the governor. Smith was quickly booted from the city, eventually relocating his scam empire to Alaska. There he was killed by a local vigilante group in 1898.

Lou Blonger, 1895-1922

Lou "The Fixer" Blonger took over the Denver underworld after Smith's departure, consolidating all of the city’s competing gangs and becoming the state's first bona fide organized crime boss. He also escalated the scams, going from loaded dice games in saloons to a headquarters in the American National Bank Building downtown.

Lou Blonger's mug shot, labeled in records as "King of the Bunks — 'The Fixer.'"

Westword file photo

Blonger had local law enforcement and politicians on his payroll, with rumors stating that he had a telephone in his office with a direct line to the police chief. In 1920, Blonger offered Denver district attorney candidate Philip Van Cise campaign contributions and votes, but Van Cise turned him down. Once elected, Van Cise made it his mission to take down Blonger's gang.

As reported in Alan Prendergast's Gangbuster: One Man's Battle Against Crime, Corruption, and the Klan, Blonger and 32 of his men were arrested in 1922 after an elaborate investigation organized by Van Cise, using a secret independent police force to circumvent the corrupt city police department. Blonger was sentenced to seven to ten years in prison, but died in custody in 1924.

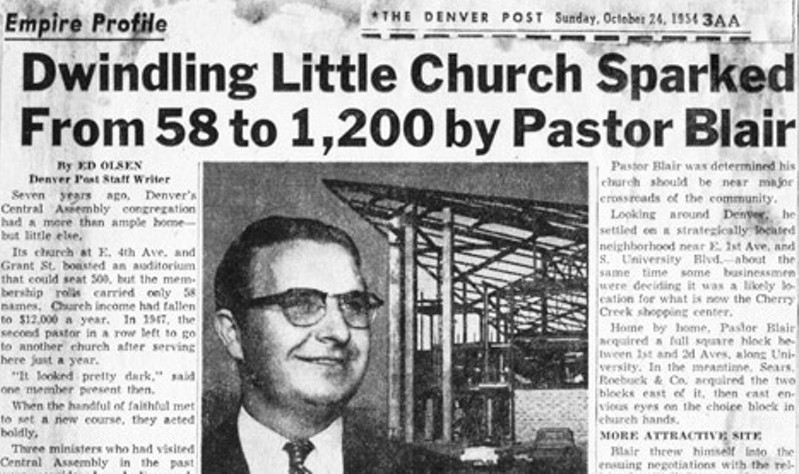

Reverend Charles E. Blair, 1965-1991

Working off of the same playbook as Regalado, Reverend Charles E. Blair of Denver's Calvary Temple defrauded his followers out of millions of dollars of donations for a godly business venture. In 1965, Blair began fundraising for the development of a nursing home and senior citizen complex called "Life Center," promising blessings to those who contributed. Hundreds of elderly church members gave Blair their life savings, hoping to secure a spot in the complex when it was finished — though that day never came.

Reverend Charles E. Blair turned a congregation of 58 into one of the city’s first megachurches.

Denver Post via Moriah Publications

In 1988, a lawsuit claimed that money raised to repay the Life Center's most distressed investors was being misappropriated. Of the $1.7 million collected in a fundraising drive, more than a third went to presumably undistressed creditors, including Calvary Temple, an advertising agency owned by Blair, various lawyers, accountants and administrators — and even $2,323 to Blair himself. Blair and his attorneys hammered out a $700,000 settlement with hundreds of investors in 1991, with the victims receiving roughly 33 cents on the dollar.

Blair remained a celebrated religious figure until his death in 2009, lauded for pioneering megachurches and television evangelism in Denver.

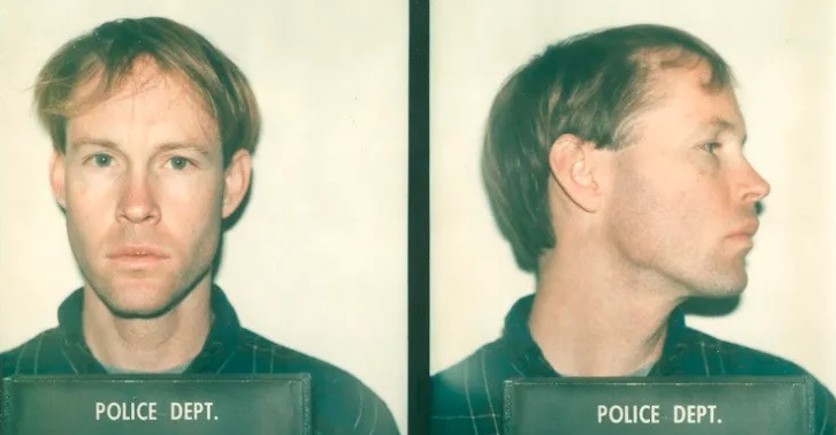

James Hogue, 1997-2021

James Hogue was named by Time magazine as one of the "Top Ten Imposters" in the country, was famously dubbed "The Runner" in a renowned New Yorker article, and was the subject of the 2003 documentary Con Man — and he spent the 2010s hiding out in the Colorado mountains.

James Hogue after he was arrested for attending and accepting financial aid from Princeton University under a false identity.

Princeton Police Department

In between his Palo Alto and Princeton scams, he fled to Colorado, where he worked on a ranch in Meredith and as a coach at a Vail cross-training camp. He resurfaced in Colorado in 1997, when he was arrested for stealing a bicycle in Aspen, and again in 2005, when police found him in possession of over $100,000 worth of stolen items from homes in Telluride, where he was working as a repairman. After a year of running, Hogue went to prison until 2012. Four years later, he was arrested when police discovered an illegal shack he constructed on Aspen Mountain.

Hogue was charged with felony possession of burglary tools, theft and obstructing a peace officer in 2017. He was sentenced to six years in prison but released on parole in February 2019. He returned to Aspen and was again arrested in January 2021, this time for the low-level offenses of stealing power from an apartment building and illegal parking.

Rick Strandlof, 2007-2011

In Colorado Springs, Rick Strandlof was known as Rick Duncan: a disabled Iraq War veteran, survivor of the 9/11 Pentagon attack and anti-war, veterans’-rights advocate who founded the Colorado Veterans Alliance. In reality, Strandlof was a high school dropout from Montana who had never served in the military, but had served jail time for car theft and forgery. During one of his sentences, he sued the jail over its ban on hard-core porn, calling it unconstitutional.A drifter and an ex-con, Strandlof moved to Colorado in 2007 and immediately forged a new identity as a war hero. Two years of lies made him one of the state's leading veterans'-rights advocates; he testified on veterans' issues at the Colorado Capitol and was featured on the campaign trails of politicians including now-Governor Jared Polis and former congressional candidate Hal Bidlack, a retired Air Force officer and actual survivor of 9/11 whose story is believed to have inspired some of Strandlof's lies.

The truth of Strandlof's deception was exposed in 2009 after a boardmember of Strandlof's veterans' organization called the naval academy he claimed to have graduated from and found no record of his attendance. The story quickly spread nationally. Strandlof was investigated by the FBI for possible fraud and charged with stolen valor. The case was later dismissed when the Supreme Court ruled that the Stolen Valor Act violated free-speech rights.

Strandlof reappeared in Denver in 2011, going by the fake name Rick Gold and posing as a Jewish lawyer; he also hung out with Occupy Denver. "I am nothing special," he said when unmasked. "There will be those who claim that I am a terrible human being and should have all manner of terrible things done to me as a result. They are probably correct. Or not."

Megan Hess and Shirley Koch, 2010-2018

For eight years, the operators of Sunset Mesa Funeral Home in Montrose illegally sold the bodies or body parts of hundreds of victims without the knowledge or consent of the victims' families. As the families paid for their loved ones to be cremated and returned, Megan Hess and her mother, Shirley Koch, stole the bodies, giving the families fake ashes or the ashes of other people so they could sell the bodies for research purposes.

Megan Hess (left) and Shirley Koch (right) are serving up to two decades in prison.

Montrose County Sheriff's Office

The funeral home owners also shipped bodies that had infectious diseases like HIV and hepatitis, falsely telling the buyers that the remains were disease-free.

Hess and Koch were arrested and charged in 2020. They each later pleaded guilty to mail fraud and aiding and abetting. Hess was sentenced to twenty years in prison, and Koch was sentenced to fifteen years in January 2023.

Briana Augustenborg, 2012

Briana Augustenborg fooled the town of Gypsum in 2012 with the tale of a nine-year-old terminal leukemia patient named Alex Jordan who loved the Eagle Valley High School football team. The mountain community rallied around Alex, giving him a signed football and merch from the team, stenciling his name onto the football field's fence and pasting A's onto the players' helmets. A Facebook page shared his story, as did local journalists. But not only did Alex not have cancer — he didn't exist at all.Twenty-two-year-old Augustenborg seemingly made the sick child up out of thin air, claiming to be a friend of Alex's family when first telling the tale to her co-worker, a parent of a player on the football team. The story soon spread to the rest of the team and then to local journalists. She chose a photograph from a cancer foundation's website to be Alex and wrote letters to the team from the fictitious child.

After pushing off Alex's promised appearances at the football team's games and practices, Augustenborg posted on Facebook that Alex had died of his cancer, with the local newspaper even publishing an obituary. When suspicious community members were unable to find a death certificate, they contacted the police.

Augustenborg was caught, and the news of her strange lie went national. However, she apparently never faced any criminal charges, as she did not try to solicit money for Alex — only attention.

Aaron Clark, 2020-2022

First appearing in Colorado in 2020, Aaron Clark quickly shot to the top of the local tech scene. His company, Equity Consultants, won the 2021 Startup of the Year award from the Boulder Chamber of Commerce. That same year, his new venture, Justice Reskill, received funding from some of the state's most prominent venture capitalists, and he appeared alongside Governor Jared Polis during a bill-signing ceremony. But his success was built on the backs of defrauded employees.More than a dozen of Clark's employees reported going weeks or months without any paychecks as Clark blamed the payroll platform or the state or the IRS for the delay. He'd ask employees to give each other money to help the neediest among them to pay their bills, occasionally offering loans himself, which he'd force them to repay. Workers and companies saying Clark owes them money estimate at least $500,000 in unpaid wages.

Clark's behavior isn't exclusive to Colorado. Contractors said they never got a dime for their work with Clark's California company in 2018. In 2007, he was caught embezzling funds, forging checks and stealing equipment from his job, resulting in a brief jail stint. In 2012 he ran a farm, with reviews from customers who never received products they'd purchased. In 2013, he ran a scam renting the same room to numerous people, collecting thousands in deposits but never giving them the keys. In 2014, he opened a juice company and was accused of not paying his vendors or employees.

After his Colorado con was uncovered in 2022 and lawsuits began rolling in, Clark fled the state before he could face trial.

!["What if I get this wrong?" Eli Regalado asked of his new cryptocurrency. "It's not on me, it's on [God]."](https://media1.westword.com/den/imager/colorado-con-artists-denver-crypto-pastor-isnt-the-states-first-famous-fraudster/u/magnum/19030843/crypto_pastor_scam.jpg?cb=1706571661)