The area around the underpass has the highest rate of wildlife-vehicle collisions on I-70 east of the Eisenhower and Johnson tunnels; the goal of the new crossing is to reduce those crashes while still allowing wildlife to go from one side of the highway to the other. Across Colorado, wildlife-vehicle collisions are estimated to cost the state $80 million a year.

The Colorado Department of Transportation built the underpass as mitigation for the Floyd Hill expansion project, which is adding lanes to I-70 near Floyd Hill from west of Evergreen to Idaho Springs. Although this underpass isn’t within the boundaries of the project, environmental evaluators determined that an underpass would have a bigger impact closer to Lookout Mountain.

Julia Kintsch, a wildlife crossing and connectivity expert with ECO-resolutions, has helped CDOT design such projects for years; she'd seen that elk, deer and coyote had all approached the highway in area between Lookout Mountain and Genesee but didn't have a way to cross. “I remember thinking back then, ‘Gosh, this would be such a great location for a large underpass,’ but never really thinking that it was actually going to happen — and now it's there,” Kintsch says.

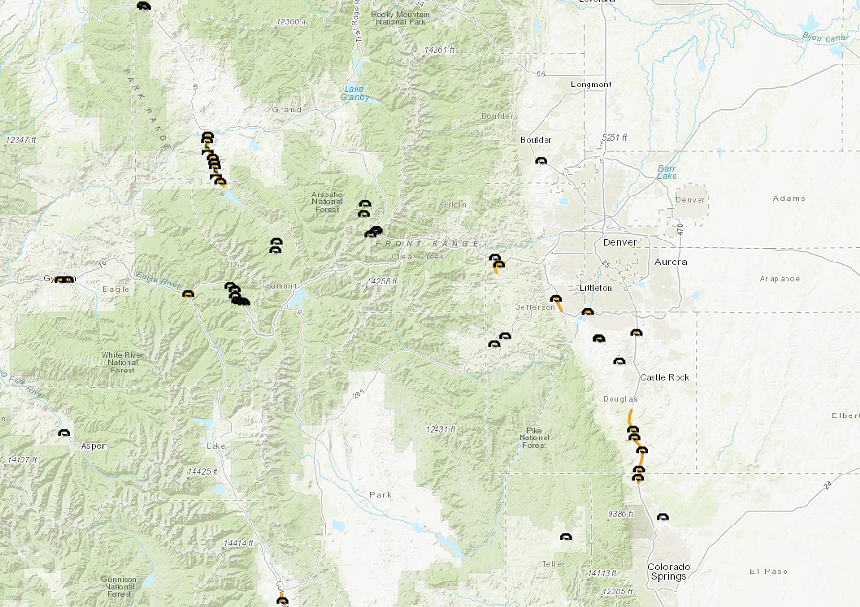

Across Colorado’s highways, there are over 100 structures that help wildlife navigate roads and connect to the environment on the other side; the infrastructure helps animals rebound from disruptions to their habitat from roadways. Overpasses, concrete culverts, underpasses and bridges all contribute, as do 450 miles of fencing to direct animals to use those structures rather than attempt at-grade crossings. Crossings usually include escape ramps made of dirt in case an animal somehow gets stuck between the fencing and the highway barriers.

According to Michelle Cowardin, CPW’s wildlife movement coordinator, animals may not be able to get everything they need if a highway cuts off access to land; they could be separated from their winter range or others in their species, which could impact genetic diversity.

“CPW has been constructing crossing structures, but on different scales, for probably upwards of forty years, if not longer,” Cowardin says. “But they weren't always built as a system, or with adequate sizing, or with appropriate fencing to guide animals to use the structure.”

But that's changed in the past decade; the state's three wildlife overpasses have all been built since 2015.

Two are on State Highway 9, which connects I-70 to Steamboat Springs. According to Cowardin, the Highway 9 project was the first comprehensive crossing system in Colorado. The crossing system is ten miles long and has five other places for wildlife to cross the highway in addition to the overpasses.

“It's still one of our largest systems in the state,” Cowardin says,

And it’s been extremely successful, reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions by over 90 percent since its completion. Mule deer made 112,000 successful crossings in five years after the system was built, Cowardin adds.

“That's the most ever documented in the United States,” she says. “Part of that is because that's winter range, so State Highway 9 animals are in that area from late October through April, and they're making movements daily.”

Animals from Summit County, Grand County and North Park have all used the Highway 9 crossing to reach their winter range. The success inspired the state to begin investing in other comprehensive wildlife crossing systems.

Colorado Focuses on More Wildlife Crossings

CDOT and CPW hosted the inaugural Colorado Wildlife & Transportation Summit in 2017 before forming the Colorado Wildlife & Transportation Alliance in 2018. Along with the two state entities, the Southern Ute Tribe, Colorado Department of Natural Resources, U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife, the National Park Service and many local recreational groups are involved.The Alliance identifies priority areas for crossings and determines how to maximize limited funding. Kintsch helped author studies in 2019 and 2022 focusing on the Western Slope and the Eastern Slope and Plains. They identified the top 5 percent of highway stretches that needed to be updated, looking at crashes, gaps in connectivity and land ownership near highways; the existence of endangered species or species at risk was also considered, Cowardin says.

The study's top priority areas account for 400 miles of roadway.

In areas where CDOT is already planning construction projects for other reasons, the Alliance still works to identify how wildlife crossings could be implemented, and how to accommodate impacted species.

Bighorn sheep have been documented using both over- and underpasses, but tend to prefer overpasses. Pronghorn sheep, elk, deer and moose have also used both structures on Highway 9, according to Cowardin.

Mountain cats like bobcats and lynx eschew overpasses for underpasses, because they typically exist near drainage areas where there might be extra cover. Even bears have used some of Colorado’s underpasses.

If there are large herds of animals, overpasses or large span bridges work much better — but if underpasses are wide enough and not too long, most animals will still use them.

“You have your pie in the sky that you really want to match your species, and then you have reality, where you also have to match it to topographic and geology features on the landscape,” Cowardin says.

The third overpass in Colorado is on U.S. 160 between Pagosa Springs and Durango, which was built in partnership with the Southern Ute. That stretch of highway also has an underpass.

New and Upcoming Wildlife Crossings Along the Front Range

Most underpasses are on smaller, two-lane highways, but CDOT built four new crossings underneath Interstate 25 as part of the I-25 Gap project between Castle Rock and Monument. Those crossings are underneath large span bridges, with plenty of space for deer and other animals to navigate. In December, CDOT received $22 million from the U.S. Department of Transportation to build an overpass between Denver and Colorado Springs called the Greenland Wildlife Overpass Project. Before the I-25 Gap project, CDOT estimated that there was one wildlife-vehicle collision every day; the improvements are expected to decrease those incidents by 90 percent.

Current construction on West Vail Pass to add passing lanes and reconstruct several bridges for safety reasons will add wildlife crossings to the top five miles of the pass, where there are no crossing zones currently. CDOT plans to build two underpasses for elk and deer species, as well as several culverts designed for lynx.

“We know we have lynx up there, so we're hoping that they'll take advantage of these smaller culverts,” Cowardin says. “Also, maybe species like bears, foxes, coyotes might use them. They're going to be long, so we're not sure how the animals are going to respond.”

The stretch of I-70 from Copper Mountain to East Vail Pass has long been a target of advocates who want to see more wildlife crossings. Summit County Safe Passages, a nonprofit group, has been working to make those crossings a reality; the idea is to extend existing wildlife-accessible bridges under eastbound lanes to the westbound lanes with fencing and add three additional crossings under the westbound lanes.

“This would create a comprehensive system of wildlife crossings and fencing that would allow animals to cross under both the eastbound and westbound lanes of the interstate,” Kintsch says. “Ultimately, all of this will connect together across the east side and the west side of Vail Pass. While we think about it administratively as the east side and the west side and Summit County and Eagle County, it's really one landscape from a wildlife perspective.”

The Denver Zoo and nonprofit Rocky Mountain Wild have an initiative called the Colorado Corridors Project that uses volunteers to monitor cameras along I-70 to track wildlife that might be trying to cross the interstate. Around East Vail Pass, the project has spotted the farthest-north breeding Canada lynx in Colorado, along with elk, deer, moose, bighorn sheep and thirteen different carnivore species.

Kintsch chairs the Safe Passages board; the nonprofit formed in 2017 after she worked with the U.S. Forest Service for years to identify the need for better wildlife connections on Vail Pass. “We recognized that this wasn't going to happen anytime soon unless outside forces galvanized around it and really helped CDOT to advance a project on East Vail Pass,” she recalls.

CDOT is now in the design phase of the project, and Safe Passages has helped lock in funding to pay for the design by partnering with Summit County to get funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation to leverage state matching funds set aside in 2022 by the Colorado Legislature. Those efforts have netted enough cash to support 60 percent of the design process.

The federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Act had allocated $350 million over five years for wildlife crossings, which provided funding for the I-25 Greenland Project; Safe Passages hopes to access the next round of federal funding to complete the design process.

Along with looking at East Vail Pass ideas, CDOT is conducting a feasibility study near Raton Pass on I-25 and also considering an overpass on U.S. 40 outside of Empire for bighorn sheep as more mitigation for the Floyd Hill project.

As state officials work to make these crossings safer, Cowardin asks people to use caution when heading to the mountains. “We need to realize the impacts of that travel on wildlife populations,” she says. “Our roads fragment wildlife habitat almost anywhere where we have road systems. … We need to stay alert and decrease our distracted driving and also watch our speeds.”