This past week, Colorado state lawmakers gathered at the Capitol for an emergency effort to slash state property taxes by hundreds of millions of dollars, cutting government funding for public schools, health care and other essential services.

This wasn’t a Republican-led endeavor: Colorado’s Democratic governor called the special session of the Democratic-controlled legislature. Nor was it a matter of out-of-control state taxes, as the state already boasts an extremely low property tax rate, and legislation passed this May further reduced taxes by $1.3 billion.

Instead, lawmakers say they were forced to cut property taxes further to keep measures introduced by a dark-money group and a Colorado tycoon off of the November ballot. If enacted, these measures would lead to far deeper property tax cuts of more than $2 billion per year.

It’s a warning for the rest of the country: In effect, legislators were engaging in negotiations with shadowy groups trying to hijack the state’s ballot process, with the state itself being held hostage. Representatives of the dark money groups weren’t in attendance at the Capitol — meaning that lawmakers were negotiating with political operatives they couldn’t see, and who are bankrolled by donors who the law allows to hide their identity.

“I don’t trust the folks who wouldn't even show their face in this room today,” said Representative Leslie Herod to other members of the House Appropriations Committee.

The Colorado special session hints at a new dark-money tactic that could shape state politics across the country. With unlimited budgets and little accountability, billionaires and dark-money groups can simply threaten to include measures through “citizen-led” ballot initiatives and force lawmakers of both parties to deliver what they want. Critics say this strategy allows magnates to hijack the ballot while bypassing much of the tedious and expensive campaign process.

“No one is asking the bigger question, which is: Who are we negotiating with, and how is it okay to take a legislative process hostage?” says Scott Wasserman, former president and current lobbyist for the Bell Policy Center think tank, a progressive nonprofit focused on economic mobility for Coloradans. “We are in a new era in which dark money is now a third chamber in the legislature.”

The agreement to lower property taxes by hundreds of millions, as opposed to billions of dollars, was part of an opaque backroom deal between the governor’s office, a dark-money group called Advance Colorado, and Colorado Concern, a nonprofit that represents business leaders. If the bill were to pass, the groups pledged to withdraw their two measures and remove the threat of what has been described as “draconian” property tax cuts statewide.

According to an analysis by Colorado General Assembly Chief Economist Greg Sobetski, more than half of the savings from the tax-cut bill would go toward commercial and other nonresidential properties, not homeowners.

By design, not much is known about the dark-money group behind the ballot initiatives, as such organizations are not required to disclose the names of their donors. But according to past reporting and information shared with The Lever, Advance Colorado — the state’s most prominent conservative dark money group — is funded by billionaire businessman Phil Anschutz, the wealthiest resident of Colorado and owner of 434,500 acres of land across the country.

“We’re here doing this for this special session because a decision was made to negotiate with oligarchs. This is a very, very small number of unelected, unaccountable individuals with extremely deep pockets,” Representative Stephanie Vigil, a Democrat from Colorado Springs, said during a House meeting on the bill. “This was a deal that was drafted and stakeholded in a backroom by people who will never have to answer to you for the outcomes.”

The influence of dark-money groups on state ballots already extends far beyond Colorado.

In Ohio, the Leonard Leo-backed dark-money nonprofit Protect Women Ohio fought a ballot measure that would enshrine reproductive rights in the state. Similarly, in Texas, billionaire oil tycoon Tim Dunn helped form a dark money group to push for a private-school voucher program that would hurt the state’s public school system. The Sixteen Thirty Fund, a liberal dark money group that receives funding from Swiss billionaire Hansjörg Wyss, has also spent millions on ballot campaigns across a wide array of states over the past six years.

As Colorado legislators worked to negotiate with unseen powerful forces this week, other dark-money operatives around the country were surely watching, said Denver-based progressive policy advocate Deep Singh Badhesha: “One hundred percent this is going to influence other groups.”

“This Stuff Was All Bound To Happen”

Ballot initiatives were designed to allow citizens to propose laws and constitutional amendments. They “have been a staple of our civic life since at least the 17th century” and serve as a window “into voters’ thinking about issues over time,” according to Leslie Graves, founder of Ballotpedia, the digital encyclopedia of American politics and elections. Yet over the years, the ballot box has become increasingly exclusive to the rich: In 2022, the average signature drive to get a measure on the ballot cost $4 million in logistical and legal expenses. That leaves just wealthy individuals, who see ballot measures as a way to promote their personal interests with less legislative bureaucracy standing in their way.

Ballot measures can lead to laws that “you will never get through the legislature, any legislature — Republican legislature, Democratic legislature,” Charles Munger Jr., son of Warren Buffett’s business partner at Berkshire Hathaway, told Bloomberg.

In 2018, 25 billionaires — including Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, liberal billionaire George Soros, and California environmentalist Tom Steyer — doled out more than $70.7 million on ballot campaigns in nineteen states where they did not reside, according to reporting by the Center for Public Integrity, an investigative nonprofit news outlet.

Additionally, from 2017 to 2023, the liberal Sixteen Thirty Fund donated more than $78 million to 33 ballot campaigns, including reproductive-rights and minimum-wage measures, across eighteen states. Nearly 90 percent of these ballot measures passed, according to an analysis by Ballotpedia.

Whether or not people agree with the measures being passed, critics say billionaire-backed ballot campaigns manipulate the idea of citizen initiatives and set a dangerous precedent of the superrich buying state ballots and swaying voters.

This election cycle, dark-money groups are on track to shell out more contributions to political groups than ever before, reaching more than $162 million in 2023 alone, according to OpenSecrets, which tracks campaign finance and lobbying. This spending will likely outpace the prior record of $660 million during the 2020 elections.

With such gargantuan budgets and little transparency about the people and motives behind their operations, dark-money groups are now able to simply threaten sprawling election campaigns to force lawmakers to do what they want.

“It all goes back to Citizens United,” says policy advocate Badhesha, referring to the 2010 Supreme Court decision that enabled corporations and other outside groups to spend endless funds on elections. “Once we let unlimited money play into politics, this stuff was all bound to happen… It’s slowly going to trickle into every single municipality and every single state in the country.”

Death by a Thousand Tax Cuts

States including North Dakota, Alaska, Pennsylvania and Arizona have either attempted to pass or successfully passed legislation to address dark money in politics through campaign-disclosure rules and prohibiting foreign contributions. But what is happening in Colorado may give dark-money groups new ideas for circumventing such guardrails — by leveraging the threat of their massive slush funds without actually deploying them. The current state of the Colorado General Assembly raises “big questions about the role of money and who exactly is in charge in a state where dark money groups can spend up to however much they want to move something forward, even though it’s bad for the state,” says Wasserman of the Bell Policy Center.

The two Colorado ballot initiatives in question, Initiative 50 and Initiative 108, would cap property tax revenue growth and reduce assessment rates that determine a property’s value and resulting tax. If both passed this November, the state would lose more than $2 billion in property taxes.

The measures were introduced after Colorado lawmakers passed more than a billion dollars’ worth of tax cuts this spring — legislators’ fourth tax cut in five years.

On August 29, in an attempt to hold off these ballot measures, a bipartisan group of Colorado lawmakers passed a fifth tax cut at the end of their four-day special session: House Bill 1001. The bill would cut 2025 taxes by approximately $247 million, and 2026 taxes by $271 million, according to legislative council staff.

School districts are expected to lose a total of $136 million in property-tax revenue in 2026, while local governments face cuts of $119 million that same year, according to reporting by the Colorado Sun.

Meanwhile, the bill would save the average Colorado homeowner less than $100 in taxes each year. This is on top of the tax-cut bill that passed this spring, which will “most benefit white or Asian homeowners and those with above-average income,” according to Axios.

During the special session, some lawmakers tried to shift more of the tax savings to lower-income households — only to have their proposals rejected by moderate Democrats and Republicans.

House Bill 1001 now heads to Governor Jared Polis, who says he’ll sign it as soon as the two ballot measures are withdrawn — something that has to happen by September 6. According to the backroom deal between Advance Colorado, Colorado Concern and the governor’s office, the conservative groups promise to keep similar initiatives off of the ballot for six years if the bill is signed into law.

Polis was a guest at the recent American Legislative Exchange Council gathering of conservative lawmakers and corporate lobbyists in Denver, where he boasted about his record of cutting taxes. “You got to lean into personal property rights,” said Polis, who was the first high-profile Democrat to speak at the convention in recent history.

But some critics point out that the deal Polis and lawmakers worked out is dependent on the whims of shadowy oligarchs and special interests, and nothing is stopping them from moving forward with their threatening ballot measures this year or other years, despite lawmakers’ desperate attempts to appease them.

It’s why some progressive lawmakers said they would have preferred to not negotiate with these powerful interests and instead focus their energies on making sure voters rejected the ballot measures in November.

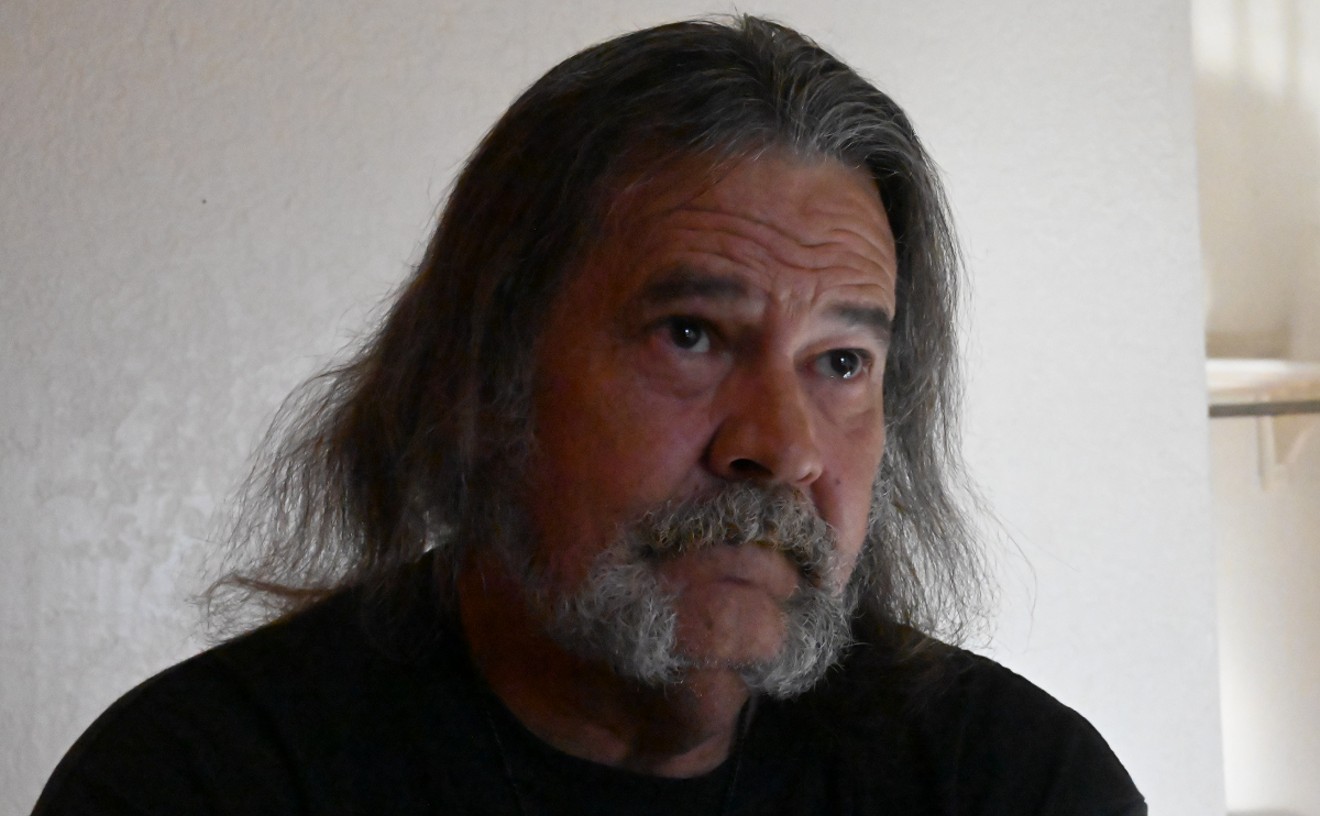

“There was a group of us progressives who were willing to fight this at the ballot box,” says Representive David Ortiz, a Littleton Democrat. “The ballot process has been utilized to great effect by really wealthy interests.”

While it’s possible that refusing to negotiate with dark-money groups would have led to far steeper tax cuts being passed this fall, critics say the precedent set by Colorado lawmakers could lead to even more troubling consequences in the future.

“If we’re not willing to work hard, if we’re not willing to stand up to bullies, then this is bound to happen,” says Ortiz. “If this tactic is going to work, what’s to stop [dark money groups] from using it again?”