As one of the planet's premier facilities for treating spine and brain issues, Craig doesn't typically admit patients in great shape — and Enstrom, the seventy-year-old namesake of Grand Junction-based Enstrom Candies, maker of world-renowned almond toffee, and a longtime power player in Colorado Republican politics, was no exception. A few weeks earlier, he had been near enough to death at an Alaska medical center that "I had a priest putting the oil on my forehead more than once," he reveals. But while his odds of survival had increased dramatically since then, he was still essentially paralyzed, with significant movement in only one arm.

Which is why Linda Enstrom, Rick's wife of 49 years, was shocked by what happened next. "His first day at Craig, they showed him a motorized wheelchair and put him in it," she remembers. "I said, 'Do you really want to do that?,' and they were like, 'He'll be fine.' I thought, 'Okay. If anything happens, at least we're close to a hospital.'"

Enstrom avoided flinging himself to the floor in his initial ride, and over the next several days of a stay that lasted nearly three months, he grew skilled enough at maneuvering the contraption that he was able to travel beyond the hallway outside his room to more appealing locations.

Among his favorite spots, he notes, was "the walkway between the two buildings at Craig. When I could tell there was a new guy, I'd pull up and go, 'What are you in for?' We'd start talking, and I'd say, 'Let me tell you how I got in here. I got a mosquito bite.' Invariably, they'd say, 'A fucking mosquito bite?' And I'd say, 'Yeah, a mosquito bite.'"

Turns out the insect carried West Nile virus, a malady capable of causing serious brain infections. When the first Colorado case of West Nile was identified in 2002, concern was high, for obvious reasons; more than sixty people died from it the next year. But the numbers tumbled after that, resulting in annual case counts usually well under 100 and fatalities in the single digits — and victims often had pre-existing conditions. These declines, coupled with the rise of far more lethal viruses such as COVID-19, caused West Nile to seem more like a nuisance than a serious threat to the populace.

But this scenario has changed. In 2023, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment confirmed 600-plus cases and over fifty deaths from the virus, the highest totals since the early days. For each of the past two years, Colorado has had the nation's most troubling West Nile stats. Last year, California came in second, with 433 total cases out of a far larger population.

Given these developments, Enstrom's experience is a tale that's both cautionary and hopeful. He continues to spend most of his days in a wheelchair. But after countless hours of rehabilitation fueled by a relentless work ethic that belies his reputation as a gleefully mischievous bad boy, he now has at least some movement in all of his major limbs and is learning to walk again with assistance from the team at the PEAK Center, Craig's adaptive health and wellness gym. He graduated to outpatient status after his late-December hospital release but visits PEAK at least a couple of days each week.

West Nile hasn't squelched Enstrom's ability to make noise in the political arena, as seen by his role in turning an unwise post sent out by state Representative Steven Woodrow after the assassination attempt on former president Donald Trump into a national cause. But his commentary continues to be marked by a cheerful demeanor that's evident even as he recounts the darkest moments of a laborious journey that has many more miles to go.

"Who can I be mad at?" he asks. "I can't call Joe Ramos and have him sue a mosquito's ass."

Rick Enstrom was put in this chair by a lowly mosquito bite, which transmitted the West Nile virus.

Michael Roberts

Cut to 2012, when a group supporting Enstrom's Democratic opponent in the race for Colorado House District 23 sent out mailers claiming he'd been busted "for selling cocaine paraphernalia out of his business." Enstrom struck back, pointing out that he had no arrest record and stressing that the charges against him were "dismissed with prejudice," but he lost the election anyhow. Years later, the impact of the claims strikes him as flat-out hilarious. "I was just a-head of my time," he jokes.

The Enstroms, including sons Brendan and Eric, subsequently settled in the Denver area as the candy empire expanded. After I joined Westword in 1990, we reconnected and grew so close that when my wife went into labor with twin daughters around 2 a.m. on a day in May three years later, we dropped off our preschool age son, Nick, with them at a highway exit on our way to the hospital. When we called later to make sure everything was okay, Nick told us with tremendous enthusiasm, "I had Coke for breakfast!"

Coca-Cola, that is. No paraphernalia needed.

Instead of being put off by this incident, we asked Rick and Linda to be godparents to one of our girls. After all, his questionable qualities (each year, he imports enough illegal fireworks from Wyoming to create his own solar flare) are more than counterbalanced by Linda's good ones.

"All my friends call her 'Saint Linda,'" Rick says. Linda insists they're kidding, but they're definitely not. Since Enstrom was hit with West Nile, she's seldom left his side.

Linda first became aware of Rick when she was a junior-high freshman and he was a sophomore at a high school in Fruita, a community outside Grand Junction — and she wasn't impressed. Sure, he was tall, handsome and the offspring of Western Colorado royalty: His grandfather Chet founded the ice cream company that evolved into Enstrom Candies in 1929 and later served in the Colorado Legislature, and his father, Emil, turned the family business into a globally known brand when he took over in the 1960s. (The main overseers today are Rick's sister Jamee and her husband, Doug Simons.) But seeing Rick force a kid to give up his seat on an activity bus transporting them to an event, "I thought he was a punk," she admits. "It wasn't until I met him after I got to high school that I realized he wasn't like that."

Four years later, the couple married, and over their time together, Enstrom flirted with a slew of ancillary professions and pastimes. "I've been a pilot," he says. "I have a boat captain's license. I'm a nationally registered EMT. I was a firefighter. I was busy as a child, and I'm still a child."

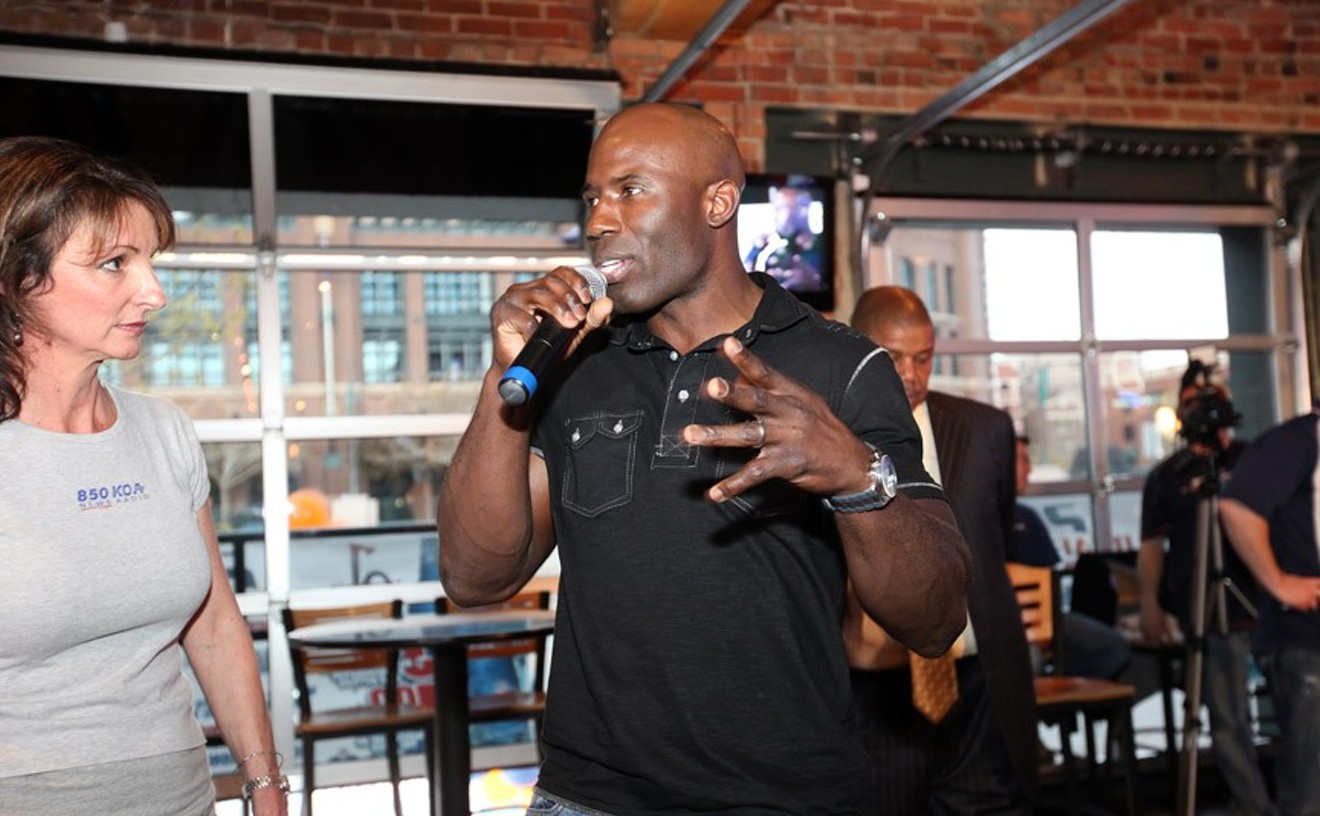

The one consistent thread was Republican politics, which he practiced with varying degrees of success. Although he was elected a Mesa County commissioner in 1978 while in his early twenties, he lasted only one term; he feels the gig was doomed by the collapse of the Western Slope oil shale industry. But in Denver, with Linda in charge of day-to-day operations at the candy branches (Enstrom handled marketing), he worked behind the scenes for the state GOP and was rewarded in 1999 when then-Governor Bill Owens named the avid hunter, fisherman and Second Amendment advocate to his dream job, state wildlife commissioner. He served in the role for eight blissful years while making time for side hustles such as overseeing George W. Bush's forces in a pivotal Iowa county as the 2000 presidential campaign wound down. He's been a multi-time invitee to the White House, including in 2017, under the auspices of Donald Trump. More recently, he became a confidant of controversial once-and-future congresswoman Lauren Boebert, whom he calls "a friend — and when you have a friend, you stand by them."

Still, Enstrom took a step back from politics out of disillusionment over the direction in which his party is headed. "We had a bunch of mean-spirited Republicans down there, and I couldn't stomach it — so we let them go have their fun," he says. "Right now it's a mess. You've got Dave Williams out there making fun of gay people. It's like, what in the world?"

Williams, the chair of the Colorado Republican Party, publicly advocated for burning Pride flags last month, even as Denver PrideFest celebrated its fiftieth anniversary; on June 25, he lost the Republican primary to Jeff Crank in the 5th Congressional District.

An infinitely more profound blow struck the Enstroms in 2021, when their son Eric took his own life amid mental health struggles. Rick retired from the candy business after that, handing his duties to son Brendan. And then things got worse.

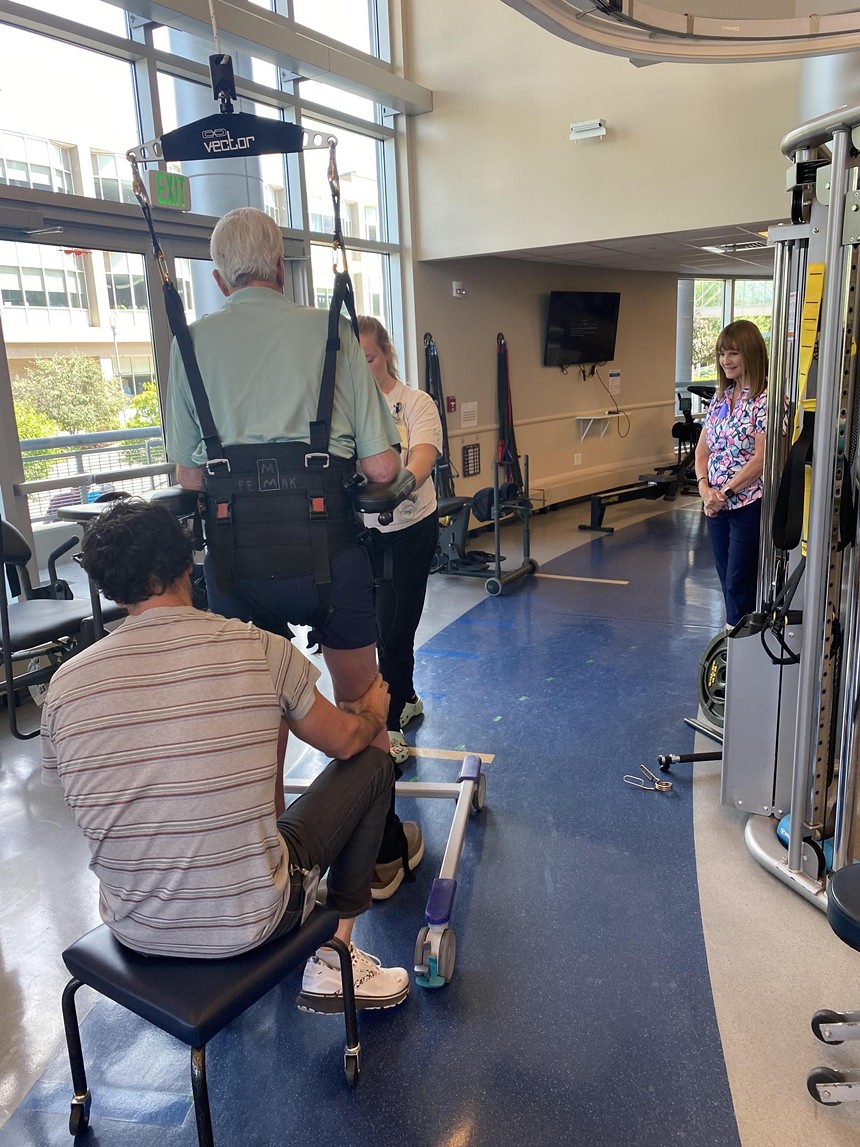

Rick Enstrom has been working with a team at the PEAK Center, a branch of Craig Hospital, to learn to walk again.

Michael Roberts

Nope. According to Enstrom, "We had dinner with a friend, I had half a drink, and then I went on the couch. That's all I remember for a while."

The next morning, Linda took Rick to a local urgent-care facility more accustomed to treating over-indulgers than folks with serious ailments — which may explain why he was prescribed an antibiotic and told to take some Tums. But back at the place where they were staying, "Rick just kept getting sicker," Linda recalls. Even with cold packs on him, his temperature climbed as high as 105 degrees. Then, when he tried walking to the bathroom in the middle of the night, he fell. Linda called the rescue squad, and responders quickly determined that he should be airlifted to Providence Alaska Medical Center in Anchorage.

For the next few days, Providence docs tried to figure out what was wrong with Enstrom, but they were hampered by a simple reality, Linda says: "They don't have West Nile virus in Alaska." The U.S. Geological Survey reports that West Nile has now been detected in all 48 contiguous states and Puerto Rico, but no human or animal cases have identified as originating in Alaska, Hawaii or Guam.

In the medical team's search for a solution, "they gave him everything under the sun," Linda continues. "It was a broad spectrum of medication, and it was so scary. I just watched him shut down. One leg, one arm, then the other leg, the other arm, then his organs."

She desperately wanted to get Enstrom to Colorado — specifically, to St. Anthony Hospital, on whose board he sits. But even after Anchorage doctors belatedly diagnosed him with West Nile, "they wouldn't fly him back because they thought it would be a lateral move — that he wouldn't get any better care there," she says. "Then one day a doctor came in and said, 'His kidneys are failing,' and that was the one thing that had stayed kind of stable. I said, 'Maybe this would be a good time to get the jet and take him home.'"

This time, doctors agreed. Enstrom survived the flight — by no means a sure thing — and the St. Anthony crew struggled to pull him back from the brink. "They were bringing in fentanyl in red pails you get at Home Depot," he says, "and I started to experience ICU delirium." He'd been hallucinating for a while; in Anchorage, he thought he'd seen a bat climb into a hole in his wall. But his Colorado visions grew increasingly surreal: flocks of remote-controlled ducks with glowing red eyes, images of people walking on walls in danger of tumbling into an abyss.

At one point, the pain was so great that he told Linda and Brendan, "Unplug me. I can't take it anymore." But the idea of losing his family was ultimately more hellish than the physical agony, and his will to live rekindled. By the time he got to Craig, he was eager to relearn skills he'd lost.

"I couldn't cough, couldn't sneeze, couldn't swallow," he says. "I'd been on a ventilator, so climbing out of that hole was hard."

One day, a whiteboard was set up in Enstrom's room and he was asked for a long-term goal to write on it. My son Nick could definitely relate to the one he chose.

"I said, 'I want a drink of Coca-Cola,'" he recalls — and after he was taught how to swallow again, his dream came true. "That first drink of Coke was the best-tasting thing I ever had in my life."

Some of the terms used to describe West Nile by medical entomologist Dr. Chris Roundy, the Colorado Department of Public Health's go-to expert on the virus, are COVID-19 call-backs.

"The effects of West Nile range from completely asymptomatic to death," Roundy says. "About 80 percent of cases are completely asymptomatic. People are infected and they don't know it. And of the remaining 20 percent, the vast majority of people feel minor flu-like symptoms — body aches, chills — that don't go any further and fix themselves over time. But in less than 1 percent of cases, people develop severe, neuro-invasive West Nile and end up being hospitalized and sometimes dying."

In 2003, the first full year it tracked the virus, the CDPHE recorded 622 cases that led to 66 deaths. Roundy believes the subsequent decrease in these metrics indicated that "we had a better handle on surveillance and control." He references another expression associated with COVID: "There was also a little bit of herd immunity."

But these theories have been shaken over the past three years. In 2021, the state registered 176 West Nile cases, the most since 2007, and twelve deaths — the first double-digit figure in eighteen years and a huge jump over 2020, when the virus claimed just one Coloradan. Matters deteriorated further in 2022, when there were 207 cases and twenty deaths. But these numbers seem modest compared to 2023, marked by 634 cases and 51 deaths.

Why such an enormous leap? That's among the questions currently being studied by scientists at Colorado State University. CSU has been among the leaders in West Nile research for years, and last August, the university inked an $8.75 million agreement with the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to establish a new center specializing in the fight against vector-borne ailments such as West Nile and Lyme disease.

One possibility for the data spike cited by Roundy: "We had a very wet spring last year, and all of that precipitation led to more breeding grounds for mosquitoes," including the Culex variety, which carries West Nile. "But they're also looking into whether there's anything different in the virus — if a different strain could have caused the increase in cases," he notes.

A West Nile vaccine for horses is available, but Roundy says a human version isn't on the horizon. Until one is, he emphasizes that the best way for people to avoid becoming West Nile victims is not to go out at dusk or dawn, when mosquito activity is at its highest. If that's not possible, Roundy recommends wearing long-sleeved shirts and loose-fitting long pants (mosquitoes can pierce through tight ones) and using "DEET or other EPA-approved repellents." Homeowners should also inspect their property regularly to get rid of standing water.

In the meantime, the CDPHE is doing additional mosquito testing and surveillance. While control efforts are mainly made at the county level, Roundy says he expects many municipalities will up their use of larvicide, which targets larvae in bodies of water but doesn't harm fish or animals, and dusk-and-dawn mosquito fogging of suspected breeding grounds.

Arapahoe County announced 2024's first Colorado West Nile case on June 26. But the CDPHE has no reports of fatalities from the virus so far this year, and Jake Manley, a Craig Hospital spokesperson, divulges that the number of patients with serious symptoms has remained steady: "We have only seen one to two patients per year for the last ten years. It remains a very rare condition for our patient population."

In other words, Enstrom is a special case — but no one knows how long he'll stay that way.

The PEAK Center's Raena Cummings and Christopher Agresta strap Enstrom into the Bioness Vector Gait and Safety System.

Michael Roberts

Jones doesn't want to give the impression that having an upbeat outlook automatically translates to healing: "There are people who try to stay positive, and they just may have a neurologic condition that doesn't allow them to improve." But she's optimistic that Enstrom's recuperative mission can keep moving forward — and his good attitude doesn't hurt. As she puts it, "He's seeing positivity. He still has impairments, but he's always full of joy, always quick to show me all of the improvements in his movements."

Prior to a visit to the PEAK Center, Enstrom demonstrates his aptitude to Jones after spotting her while making the rounds on the hospital's upper floors — and he sees plenty of other staffers who aided him in his time of need, including psychologist Katy McGuire, nurse Amanda Luna, tech Katelyn Cochran, physical therapist Barb Fritz, massage therapist Sandy Zagyl, case manager Bridget Meyers, and Ken Russo, who repairs wheelchairs while blasting rock music from his office. Each greets Enstrom like a conquering hero, and he returns the favor.

A sizable portion of Enstrom's home has been renovated to accommodate his condition, and he sleeps in a hospital-style bed in the front room; thanks to his fancy wheelchair, whose seating area can rock, tip and rise so high that he can look at standing visitors from eye level, Linda is able to help him in and out and assist him with most of his other needs. He has a daily exercise regimen, too — but there's no substitute for the PEAK Center.

On this day, the center is crowded with folks working out with technicians on various mats and specialized equipment, some in the testing phase; the gear is funded by the Craig Foundation, a philanthropic nonprofit. Many have suffered devastating injuries — motor-vehicle crashes are the top cause, followed by sports-related falls and other types of accidents — but the mood of staffers and patients alike is consistently buoyant. If there's any sadness, it's masked by determination and nurturing spirit.

On this day, Christopher Agresta and Raena Cummings have been assigned to work with Enstrom. They fit him into a Bioness Vector Gait and Safety System, which offers adjustable support to those attempting to walk again. Enstrom slides into a harness attached to a device whose track curves in a loop around the center's ceiling. In his first uses of the system, the equipment supported almost all of his weight, but now the controls hold up the equivalent of just thirty pounds. Once he's standing behind an oversized walker, the Bioness starts moving along the track, and Enstrom walks with the assistance of Agresta, who helps him bend the knee of his right leg, which he can't yet flex on his own.

Four circuits of the center is Enstrom's previous record, and he wants to break it — but it won't be easy. His face gets redder and redder from his exertions each time around, and Linda, who's positioned herself in front of him, can tell by his expression that he's expending energy quickly. But after the fourth round trip, Agresta makes it clear they'll be taking a fifth. At the finish line, Enstrom is as elated as he is exhausted.

After a break, Enstrom moves on to an exercise bicycle, electrical stimulation pads arrayed on both legs, a screen simulating a path in front of him. At first glance, he isn't getting anywhere, but that's an illusion. Every time he pumps his legs, he moves closer to his goal of getting back to the active life he lived before a certain mosquito decided he looked delicious.

Even Enstrom doesn't know if that's achievable. But he keeps pedaling.