Denver City Council will likely let voters decide if all city employees can engage in collective bargaining.

On June 24, councilmembers approved a proposal that would expand bargaining rights for city employees beyond firefighters, police officers and sheriff deputies, with a second and final vote scheduled for next month.

Although the fire department and law enforcement have had collective bargaining rights for 89 years, those who work for other departments, such as the Denver Public Library, Denver Water, emergency dispatch and other branches of city government are prohibited from collective bargaining by the city charter. If successful next month, the council proposal would ask voters this November if they want to amend the charter so that all non-supervisory city employees can unionize and collectively bargain.

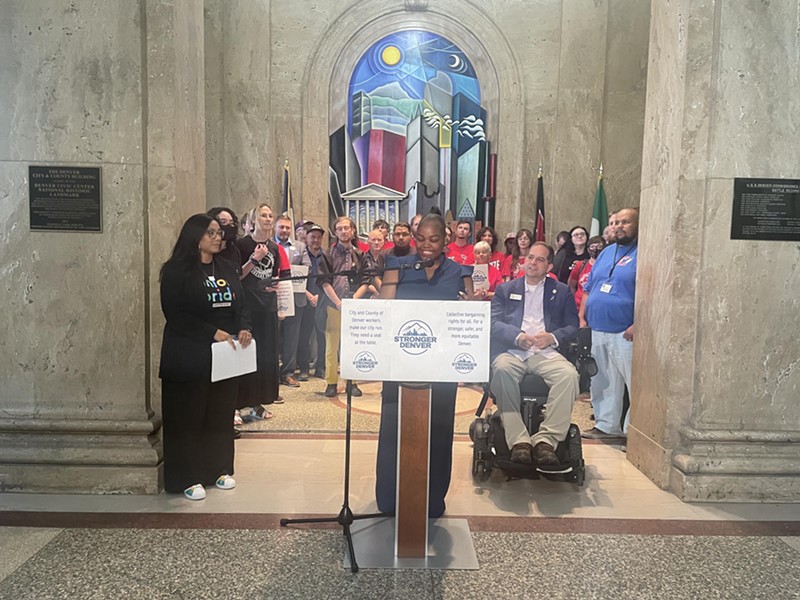

“These public workers are left without a voice in their workplace, often silenced, intimidated and unprotected in our city, and exposed to unfair treatment and unjust working conditions with no recourse,” Councilmember Shontel Lewis, one of the proposal's sponsors, said at a June 24 rally at the Denver City and County Building. “The largest change to come from approving collective bargaining for our city employees would be that they have the ability to advocate for themselves together.”

The Stronger Denver campaign went public nearly three years ago in 2021 with the goal of achieving collective bargaining for more city employees. According to councilmembers, this ballot proposal is in response to issues raised by the group.

Councilmembers Lewis, Serena Gonzales-Gutierrez, Chris Hinds and Sarah Parady introduced the idea in April. They've sinced refined the language and are now joined by councilmemembers Flor Alvidrez, Stacie Gilmore, Paul Kashmann, Amanda Sawyer and Jamie Torres as co-sponsors.

“We are working closely with Mayor [Mike] Johnston to be sure that once the voters approve the collective bargaining agreement on the ballot in November, impacted departments and agencies will be able to smoothlessly transition into the new system,” Lewis said.

The bill specifies that bargaining wouldn't begin until May 2025 or later, at which point employees could collectively bargain on “wages and compensation, rates of pay, benefits, dependent benefits, promotions and demotions, hours, working conditions, employee facilities, paid time off, leave, grievance procedures, disciplinary procedures, and other terms and conditions of employment,” according to the legislation written up by the co-sponsors.

The text of the bill also describes how employees of various departments and city entities would be allowed to form and ratify unions and bargain with their respective bosses.

If employees wanted to strike, they would have to give 21 days' advance notice so the city could determine which employees couldn't strike without threatening the public health, welfare or safety of the city — and if all employees from a certain department can’t strike for those reasons, then both parties must agree to arbitration.

Denis McCormick, an administrative investigator with the Denver Department of Public Safety, shared at the press conference that when he first started in his role five years ago, he usually had around eight to ten cases at once. Now McCormick says he has seventy cases, and the rest of his small team of co-workers are in a similar boat.

“Because it's such a small amount of people in such a big agency, it’s tough to get a seat at the table,” McCormick shared.

Library worker Mabel Darling says being able to have a seat at the table is key.

“This is not a radical thing,” Darling tells Westword. “This is a basic democratic issue for people to be able to sit at the table the same way that the police and firefighters and our teachers have a seat at the table.”

Darling calls Denver an “anomaly” among other major cities like Boston, Kansas City, Detroit and Seattle, where city employees all have collective bargaining rights.

According to Lauren Seegmiller, who has worked for the library for almost eleven years, Denver Library employees began wondering if they could unionize in 2019 when they were informed that they were now at-will employees who could be terminated for any reason. In December 2020, right in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, they began discussing their issues with paid time-off policy and safety in the workplace.

“Working with the public can be challenging,” Seegmiller says after the press conference. “It's wonderful, which is why we all do it, but it can also be challenging.”

Darling says she has always felt comfortable at her job, but has examples of injustice with others and believes a union could help.

“This is just something that needs to be in place,” Darling says. “Regardless of how good one person or one particular team might look or feel at any given moment.”

Councilman Kevin Flynn was the lone "no" vote on the measure. Flynn said he opposes the bill because he does not think it's a good idea for council aides to bargain together even though they work for different councilmembers.

A final vote on the proposal will likely take place on Monday, July 8.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]