The backup — which also flooded the boiler room for the entire D&F Tower at 1601 Arapahoe Street — was caused by an error on the part of PCL Construction, which had been awarded a $149 million contract for the 16th Street Mall Project...but didn't realize that the building was tied to city systems. Local businesses have already been complaining about all the obstacles that the lengthy construction project has created, but this mess was particularly crappy.

"Supporting local businesses is a top priority for the city," says Laura Swartz, communications director for the Denver Department of Finance, which is helping to oversee the 16th Street project. "We are committed to working closely with all businesses to ensure any issues caused by construction are mitigated quickly and efficiently." After learning of the backup, she adds, the city filed an initial claim with Zurich Insurance within 24 hours of the incident.

The D&F Tower is divided into condominiums; the basement level is leased from the Larkin family by Selene and Jefferson Arca, who run it as the Clocktower Cabaret. While waiting for PCL and the city to cover the damages, the Arcas called HRS Restoration to clean the Clocktower Cabaret and canceled shows in the meantime.

"HRS Restoration did an amazing job," says Selene Arca. "It was such a mess. Inches of standing raw sewage. Thousands of gallons of it, everywhere. Once they'd done their work cleaning everything — not just the floors, but every chair, every table, everything — we had to then replace pretty much anything that was fabric. We had to rebuild the booth. We'd just put down new carpet in November, and that was obviously ruined."

In the interest of time, the Arcas paid for everything so that the Cabaret could reopen, and soon. They saved receipts, since they'd been promised that they'd be reimbursed by representatives of the construction company, the city and their insurance adjusters. By the time the Cabaret finally did reopen, the Arcas had roughly $22,000 in repair and cleaning invoices, along with an estimated $50,000 in lost income for the ten days — including two weekends — that the Clocktower was closed.

But as of late July, the Arcas had not seen a penny of reimbursement.

"The insurance carrier has since mailed reimbursement checks to Clocktower Cabaret twice, although Clocktower Cabaret reports that they have not received the checks," says Swartz. "The city is currently working with the insurance carrier and Clocktower Cabaret to get to the root of this issue, and ensure Clocktower Cabaret is fully reimbursed."

Contacted for comment, Robyn Ziegler, Zurich's senior manager of External Communications, says that the company has no record of the case. "I am not finding anything with the name you have provided," Ziegler says. "Possibly identified differently. That said, it is not our practice to provide information about a claim to anyone other than the parties involved."

Two of the parties involved are getting tired of waiting — not just for a check covering the site damage, but also reimbursement for the loss of income. That's supposed to be handled by Crawford & Company, a claims management firm, which says it's "working on it," according to the Arcas. Crawford & Company did not respond to requests for comment from Westword.

"I'm not sure I believe they're even telling us the truth at this point," says Jefferson Arca.

"We're just at a loss," Selene adds. "It's hard for us to keep our amiable nature with them at this point. We're tiny. Twenty thousand dollars might not be much to them, but it's big for us."

The D&F Tower is no stranger to hard times. Despite its legendary status — which was an almost immediate thing, perhaps even before its construction 113 years ago — the building and its inhabitants have seen their share of challenges. Still, it remains what it was built to be: an inspirational spectacle, a brick-and-mortar symbol of the city it graces.

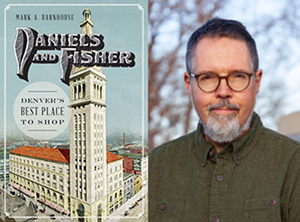

The structure began life as the Daniels & Fisher Tower, part of what billed itself as "Denver's oldest department store." According to historian and author Mark A. Barnhouse, who wrote Daniels and Fisher: Denver's Best Place to Shop, "The legacy of the Tower is inextricably linked to that of the department store. You can't talk about one without diving into the story of the other."

The store was founded in 1864, a dozen years before Colorado became a state, by a Kansas merchant named William Bradley Daniels. Hearing how Denver was growing, he sent his brother-in-law west with a wagonload of goods, and they opened a shop at the corner of Blake Street and 15th (then known simply as "F Street").

The store did well, and in 1872, Daniels brought in partner William Garrett Fisher, whose three-story neoclassical Revival-style mansion still graces the corner of 16th Avenue and Logan Street. By 1875, the venture now known as Daniels & Fisher had built a two-story store at the corner of 16th and Lawrence streets. It soon grew, expanding down Lawrence and adding two floors, then another.

Daniels died in 1890; Fisher passed in 1897. It was left to Daniels's son, William Cooke Daniels, to usher the department store out of the Silver Crash of 1893 and into the 1900s.

Sort of.

"William Cooke Daniels wasn't someone who really wanted to run a store," Barnhouse says. At the time, he was a journalist, working at one of the many New York dailies duking it out in that city. "But he'd inherited one, so he hired a friend he'd met in New York, Charles McAllister Wilcox, to run the store."

While Daniels played dilettante, moving to France for a while, Wilcox ran the show.

"The store wanted to expand again," says Barnhouse, "but they were hemmed in. They couldn't keep moving down Lawrence, because there were some buildings there already — one a hotel — that didn't want to sell out. Instead, D&F decided to bridge the existing alley and expand up to Arapahoe — and that new structure included the tower."

Construction began in 1910, and the project was finished in time for the 1911 holiday shopping season.

The inspiration for the D&F Tower itself dates back to 1902 and the collapse of the Campanile di San Marco, the bell tower of St. Mark's Basilica in Venice. That tower's foundations were estimated to have been laid in the tenth century, and although they'd been improved and reconstructed several times over the centuries that followed, the unstable marsh on which they were built could not support them. Despite some local opposition, Italy decided to rebuild the landmark, and that project captured global attention. "A lot of architects around the world began building replica towers based on the Campanile," Barnhouse says. "The Metropolitan Life Tower in New York City. A Seattle, Washington, train depot. A city hall in Melbourne, Australia. It was definitely part of the zeitgeist."

And ultimately, Daniels wanted his store to be a landmark. "After all," Barnhouse notes, "Daniels was competing by this point with a lot of other stores along 16th Street. The Denver Dry Goods, Joslin's, smaller stores like A.T. Lewis and Sons. Plus, Daniels was kind of a snob about architecture. He didn't like the idea of red brick, for example. We love our red brick buildings now, especially down in LoDo, but Daniels felt that red brick made buildings look like warehouses. I'm sure it didn't help that his competitors were all in buildings utilizing red brick, too. So he had his architect, Frederick Sterner, use the lighter blond brick in his design, and ended up refacing the existing structure in that same brick to tie it all together."

When it was finished, the D&F Tower was the tallest building west of the Mississippi River — some said west of Manhattan — at 393 feet and 21 stories, with an enormous bell that chimed on the half-hour and clock faces on all four sides of its apex that employed the same mechanics as London's Big Ben.

It fit right in with Mayor Robert Speer's "City Beautiful" movement, itself inspired by the 1893 Chicago World's Fair, introducing neoclassical design and architecture into working metropolitan areas. "It was really Denver standing up and saying, hey, we're a big city now," says Barnhouse. "The Tower was a private response to what Speer was doing in the public realm."

The Tower became one of the must-see sights for travelers, who'd climb to the observation deck near the top to scope out the city, then stop at the curio shop on the twentieth floor. "When you see a postcard or any sort of souvenir merchandise from the D&F Tower, you can bet that it was originally purchased from that curio shop," Barnhill says. "I can't imagine anyplace else in the city selling them."

Other parts of the structure served different functions through the years. There was an employee cafeteria, along with the requisite offices. There were lounges — one for men, one for women — as well as a space devoted to the schooling of the store's youngest employees: cash boys and cash girls, who'd run payments between the sales floor and the central cash office, where change would be made, then return the remainder to the customer.

The Tower even had a short-lived role in politics, which ended shortly after it opened. In 1912, the Denver Republican (a house organ of the GOP) worked out of offices directly across the street, essentially where Skyline Park is today. On election night, the newspaper arranged a tower lighting code, which Denver residents could follow to learn early voting results. In a world that would still have to wait a decade or more for the advent of radio, it was the closest thing to mass media that the city could muster.

Wilcox, who'd inherited the store from Daniels after his passing, sold it in 1929, only a short time before the stock market crash. Despite briefly entertaining an offer from a growing national chain that had made a practice of buying up regional stores like Daniels & Fisher, Wilcox wanted to keep the business in local hands.

The store survived the Depression relatively well, as it had always offered everything from bargain-basement items to exclusive departments. But the area around the fabled tower started going downhill, and the store responded in the mid-1930s by building a parking garage — Denver's first — with an entrance on the Arapahoe side. Its valet parking allowed patrons to arrive and walk right in the doors without worrying about whatever was on the surface streets. That and other efforts on the store's part led to a small resurgence during World War II, but by the 1950s, the downscaling of that part of downtown had worn D&F down to the point that the store operated at a loss for some years.

Mark A. Barnhouse and his book Daniels and Fisher: Colorado's Best Place to Shop.

The History Press/Jeremy Patlen

In the years that followed, the building at Arapahoe and 16th sat unused and passed through several sets of hands, including those of infamous Boulder swindler Allen Lefferdink, who wanted to reopen it as Tower Merchandise Mart, with showrooms where different companies could show off their wares. But that plan, too, disappeared.

At one point, it was rumored that the Denver Urban Renewal Authority, which was founded in 1958 with the goal of cleaning up — and clearing out — downtown, had plans to tear down the Tower. "Denver Post editorial cartoonist Pat Oliphant had this very famous piece that showed a wrecking ball hitting it," Barnhouse recalls. "I believe that one cartoon is the source of the myth."

In fact, DURA and the Skyline Urban Renewal Authority, established in 1965, had their eyes on the Tower. "DURA had incorporated the Tower's silhouette into its own logo," Barnhouse notes. "They'd also released drawings of the park proposal that featured the Tower as the centerpiece of the whole renewal area. So they never planned to tear it down."

And they couldn't, because in 1969 the Tower was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The original store next door was not as lucky. It was demolished in 1971, its signature bricks salvaged and set aside for whatever might come next. Throughout the ’70s, efforts were made to figure out what to do with the solo tower. For a while, its sole occupant was then-new radio station KBPI, whose owner, Bill Pierson, connected its broadcast antenna to the flagpole; he loved the de-powered clock so much that he'd walk up eighteen floors every day in order to manually wind the mechanism.

Later, a local minority-owned bank expressed some interest in the space, but that fell through. There was also talk of folding the historic structure into a new Sheraton Hotel that would use the tower floors as individual suites, but that project also moved farther up 16th Street.

Finally, in the early 1980s, developer David French came up with an idea that stuck: office condominiums, a new concept for the Mile High City.

The office-condo idea worked for many reasons, not least of which was that an office building only required the one existing stairwell, while residences would have required two, eating up too much of the livable space on each floor. Budget issues also played into the use of aluminum storefront doors at the base. In later years, some of the condominium owners raised enough money to replace them with the grand revolving doors that are there now — but aren't original to the tower, as some people believe. Rather, they were salvaged from the former Ford Motors headquarters building in Dearborn, Michigan.

Richard Hentzell purchased the sixteenth floor in 1993, when the city was experiencing an economic downturn, for "a relative bargain." He'd been fascinated with the clocktower since he was a boy in the 1950s and it was still the tallest structure in Denver.

In 1995, Hentzell filed a $100,000 grant request with the State Historical Fund to start restoring the tower's grandeur. French had handled much of the infrastructure needs, but there was still a lot to do with detail restoration. "The cupola was rotting," Hentzell recalls, "and the flagpole was non-functional. The bell was silent; the exterior brick and terra cotta were blackened from years of soot and grime. On the interior, the lobby marble was scratched and damaged; original light fixtures had been sold off by DURA along with the bronze entrance doors."

That grant request was approved, as were several that followed; the Bonfils Foundation also helped fund a total of $510,000 in renovations. It was a popular cause, Hentzell says.

"Everyone knows where you're located, and they make an effort to come downtown for a visit and to take in the view from the fourteenth-floor loggia," he says. "It gives one a great deal of pride."

These days, what's now known as the Clocktower shines with the same passion that's kept it part of Denver history for over a century.

"It's been a landmark for as long as I can remember," says Danny Newman, the Denver entrepreneur who bought My Brother's Bar with his family in 2017. "But I don't think I ever got to go in and experience it fully until a Doors Open Denver event. I was just blown away by how remarkable and cool it was."

He and his now-wife incorporated the tower into their wedding. "We held a very fun goth rehearsal dinner up there on a Friday the 13th," he laughs. "Tarot readers and Ouija boards and everything. It was awesome." About a year later, the couple saw that the top floors were for sale, and wound up buying the top five floors for $2 million in 2020.

Now they've not only opened their Clocktower Events space as a venue for other weddings and special occasions of all sorts, but they've partnered with Historic Denver to offer regular tours of the Clocktower, so that Denver residents and visitors alike won't have to wait for a Doors Open Denver-type event to be able to see it. "It's a special place in Denver," Newman says. "It was designed to be a place people wanted to see."

And people still get to — thanks to the efforts of a lot of individuals, including the Arcas. "The very first time I went down there," says Selene Arca, "I was applying for a job. The club was maybe a year old, and I remember walking down the stairs from the 16th Street Mall and finding myself in this enchanted space with sparkles and candles and everything. It was like Phantom of the Opera come to life. I just loved it, and wanted to be there all the time."

Soon she was: She married Jefferson Arca, who was part of a partnership including other members of the Arca family, singer Lannie Garrett and designer Lonnie Hanzon that leased the basement space in 2006 and turned it into the Clocktower Cabaret. Though both Hanzon and Garrett ultimately left the project, Selene and Jefferson Arca kept it going as the Clocktower Cabaret, focusing on burlesque and similar programming.

"There's magic down there; people walk in, and you can see the trouble just melting off of them," Selene says. "And then the joy on their face while they're watching something crazy on stage. That's the moment we want to create for people; that's why we do the shows night after night."

And that's why the show continues to go on. "We're trying so hard to stay positive," Selene says. "We want to be team players. We know the 16th Street Mall is going to be awesome when it's finished. It's going to be amazing and beautiful. We just want to still be here when it happens."

Hanzon, who'd created the original look of the venue and oversaw the recent redecoration project, was called in to do repairs. "Jefferson had a biohazard crew overnight, thank goodness, and the art pieces were unaffected," Hanzon says. "The place looks better than ever, but jeez, what a mess!"

"I feel really sorry for the employees and performers who didn’t get to work their shifts," says Garrett, who's now retired but occasionally does private bookings. "I’ve been in that situation, and when you’re living show to show, it makes it really hard."

But even while the shitshow took center stage in the basement, the exterior of the D&F Tower continued to put on a display of digital art, which the Denver Theatre District has hosted for years, changing out the show every month but always offering an illuminating look at the tower.

So it goes, top to bottom, then to now: The D&F Tower continues to stand. And because no history is lost that is told and retold, it seems fitting that through all the renovation and reconstruction and preservation over the years, the different-colored brick salvaged from the demolished store has remained piled up and waiting to be used.

It's a visual reminder of what was there and what was lost, what remains and what ghosts haunt the streets of yesterday's downtown, still looking up and marveling at the Clocktower that marks more than just the passage of time.