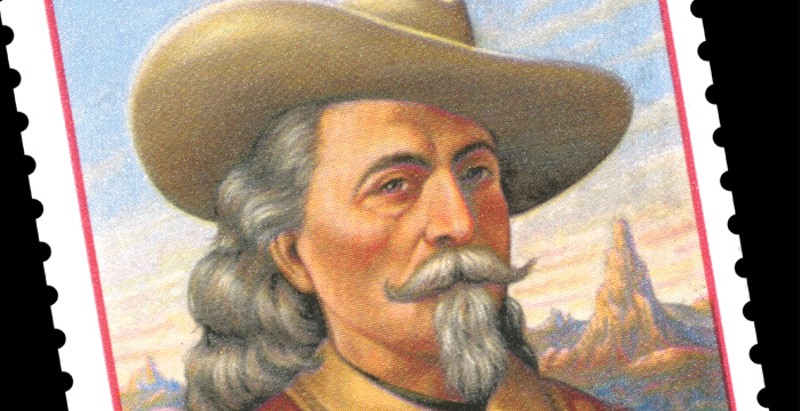

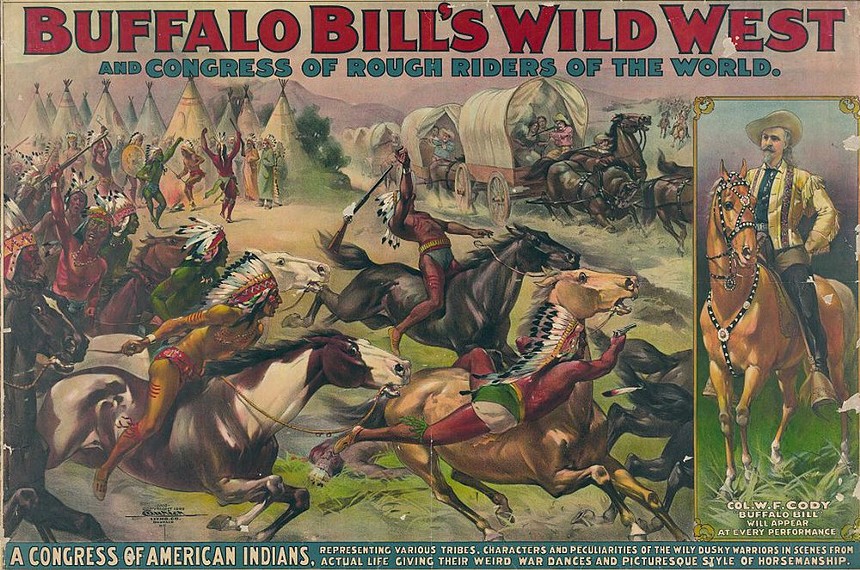

When William F. Cody, known to posterity as Buffalo Bill, shuffled off this mortal coil at his sister's Mile High City abode on January 10, 1917, at age seventy, he was one of America's biggest celebrities thanks to Buffalo Bill's Wild West, a touring company that distilled the story of how the Great Frontier was pacified into an intoxicating extravaganza — though not for Native Americans, since the troupe's Indigenous performers mainly reenacted their people's defeat. The production's popularity earned the onetime scout-turned-flamboyant impresario a level of renown generally reserved for presidents and monarchs.

No wonder a fight soon erupted over where his cadaver should spend eternity.

According to the version offered by the Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave, located in Lookout Mountain Park (a Denver Mountain Park overlooking the city), residents of Cody, Wyoming (a town the proto-superstar founded and named after himself), proclaimed that he should be interred there. But the museum account holds that friends like "unofficial foster son" Johnny Baker "affirmed that Lookout Mountain was indeed his choice" for his final resting place. On June 3, after a delay caused by frozen ground and snowy roads, his coffin was lowered into a spot "with spectacular views of both the mountains and plains."

Baker took advantage of this placement. In 1921, the same year Cody's widow, Louisa, died and was consigned to the Lookout Mountain plot, he opened the Buffalo Bill Memorial Museum in a sprawling edifice (approximate size: 12,000 square feet) that he christened the Pahaska Tepee; "pahaska" is a variation on Buffalo Bill's Sioux nickname, "long hair of the head." The museum moved into a new, separate building built in Denver in 1977, leaving more room for a restaurant and gift shop that are still going concerns.

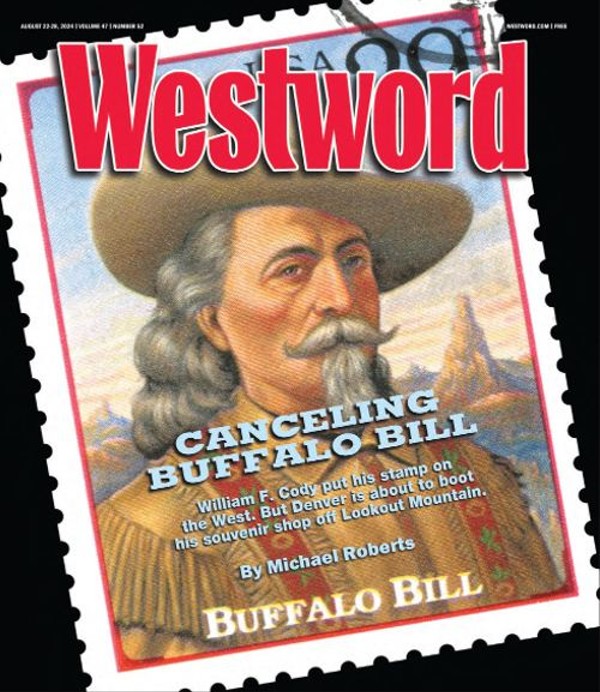

But not for much longer. H.W. Stewart Inc., a family company currently run by Bill Carle, took over the Pahaska Tepee from the Baker clan in 1956, and except for a nineteen-year gap from the late 1960s to 1988, the outfit has operated it ever since. But this past spring, the City of Denver announced that because of worries about the condition of the aging building, the restaurant and gift shop will be closed indefinitely at year's end.

The shutdown edict leaves Carle feeling heartbroken. "You're almost in tears every day," he says.

Carle gets just as emotional talking about Echo Lake Lodge, at the foot of Mount Blue Sky, which his family began managing on Denver Mountain Parks property in 1965. Denver booted H.W. Stewart from that property and closed the Lodge in 2022 based on similar concerns about crumbling infrastructure, and it's now been off-limits for two consecutive summers, with no end in sight.

The Lodge's demise left Carle with what he estimates as $300,000 in fresh merchandise emblazoned with "Mount Evans" — Mount Blue Sky's former name, which was changed last year because it honored John Evans, Colorado's second territorial governor, who created the conditions that led to 1864's Sand Creek Massacre. Carle has set up a table stacked with Mount Evans mementos outside the Tepee, with proceeds earmarked for Evergreen's Alpine Rescue Team. After he raises $10,000, he says, "I'm going to throw the rest in the dumpster."

He hopes a similar fate doesn't await the hundreds of boxes containing Buffalo Bill-related items in the Tepee's cavernous basement and all of the souvenirs arrayed throughout the retail space — but it could happen. The city is noncommittal about how long the restaurant and gift shop will be inaccessible or even if they'll eventually return in anything like their current form. The same goes for Echo Lake Lodge.

Equally unclear is the way Buffalo Bill's legacy will evolve over the coming years. Debates over whether Western figures such as Kit Carson were heroes or villains have become more heated over time, and Cody is hardly immune from such historical reconsideration. Steve Friesen, director of the Buffalo Bill Museum from the mid-1990s until 2017, and the author of several books about Cody, sees him as quite progressive for his era. But Joshua Emerson, a comedian who's also a member of the Denver American Indian Commission, says, "I hate him. Indian fighter, hunted buffalo with a rifle, and I think his Wild West show was one of the most harmful influences on this country's relationship with Indigenous people."

And then there's the matter of Cody's continued relevance, or lack thereof. While his showmanship has many modern corollaries, he's no longer as prominent a pop-cultural icon as he was for many decades after his death. Today the most recognized Buffalo Bill is undoubtedly Josh Allen, field general for the NFL team of the same name, who previously quarterbacked at the University of Wyoming.

But don't bury William F. Cody yet.

The roots of H.W. Stewart Inc. trace back to 1893, when Carle's grandparents, Orrie and Helen Stewart, began peddling keepsake newspapers and more to passengers on the Manitou and Pikes Peak Cog Railway. The company held on to the Pikes Peak concession rights until 1992, when a much larger corporation, Aramark, outbid it.

This bad break wasn't an anomaly: H.W. Stewart has experienced a pattern of losing control of long-held businesses at Colorado tourist destinations. Orrie, Helen and their heirs ran Garden of the Gods' Hidden Inn from 1948 to 1994; the Mount Evans Crest House from 1956 to 1979; and the Red Rocks Trading Post from 1963 to 2002. Carle and his associates also provided food and drink service for Red Rocks Amphitheatre from 1994 to 2002 and secured the venue's first liquor license.

"I thought hot chocolate and doughnuts sold well on Pikes Peak until I sold beer at Red Rocks," Carle confirms, laughing. "I'd never made so much money." But then Aramark won that contract, too.

H.W. Stewart's current five-year pact for the Buffalo Bill enterprise expires this year — but Denver didn't issue a request for a new proposal for reasons that Jolon Clark, Denver Parks & Recreation's executive director, says have been lingering for sixteen years.

"In 2008, a committee for a master-planning effort looked into [Denver] Mountain Parks broadly, but it also looked at that building and saw a need for it to be fully assessed for historic preservation," Clark reveals. "And there's a desperate need for that to be done. As our team looked more and more into the building, they saw major issues with rotting log structures and continuing problems with the septic system."

Anxiety over sewage was also cited to explain why Echo Lake Lodge needed to suspend service — Carle blames the city for putting in a "dumb system" that could produce a powerful stench — and the potential for such issues may be even more acute at the restaurant and gift shop because of the site's popularity. Carle says the facilities serve as many as 500,000 visitors a year and guesses that around 2,000 to 3,000 people stop by daily during warm-weather months to take in an awe-inspiring 270-degree view of Denver and its immediate environs.

In contrast, the museum's annual attendance tends to hover around 80,000, and only paying customers can use its restrooms, while the Tepee's are open to all — a big reason for the plumbing strain. Still, Carle sees no evidence of looming catastrophe. Clark begs to differ.

"Over the last several years, we have experienced mechanical failures of the lift system, a high volume of sewage that had to be manually removed, pipe deterioration and visible surfacing in the soil-treatment area," Clark outlines. "In 2022, the pump had to be replaced. The component failure registered an alarm, and even with the pump down, we had overflow of untreated sewage onto nearby terrain."

In response, Carle emphasizes that he's dealt with such challenges in the past without having to close. He recalls that when he and his family took on the restaurant and gift shop again in 1988, the building was on the verge of collapse, but they saved it by using steel supports instead of telephone poles to prop it up. He covered the repair tab, he says.

Clark acknowledges that funding for significant repairs was in short supply back then. But he says the situation changed with the passage of 2018's Measure 2A, a parks-and-open-space sales tax he championed when he was a member of Denver City Council. Now there's money to tackle what he calls "deferred maintenance" at the Tepee, the Lodge and other Denver Mountain Parks landmarks. In his words, "It's really exciting to see the moment where we start to reinvest in these things for the long term."

There's another potential factor behind Denver's move to close the Tepee, Carle believes: "They think I'm a racist."

At a February meeting, Clark revealed he'd visited the gift shop and was perturbed by some products, including a rubber tomahawk. But Clark was most upset by Chief Lollipop — a so-called cigar-store Indian whose headdress had drill holes stuffed with colorful suckers.

"Jolon said, 'There's no way that's defensible on any level,'" Carle recalls.

No equivocation from Clark: "In Denver, we strive to be inclusive at all times and create environments in our public space where everyone feels welcome and respected. So I did share that there were items that I didn't feel were in line with Denver values."

Clark says that discomfort over Carle's displays had nothing to do with allowing the present contract to lapse. Still, Carle says he "sanitized" his sales floor by removing anything that struck Clark as objectionable, despite his sense that he'd done nothing wrong. "A cigar store Indian isn't like a Civil War statue," he asserts. "It's just an Old West thing."

Friesen, widely seen as the country's most prominent Buffalo Bill expert, understands the tensions between these views. "It's Americana versus political correctness," he says. "Does it promote stereotypes? Yes, on some levels. But nobody's going to buy a souvenir of an American Indian lawyer in a suit. One has to be realistic."

Friesen encourages a similar approach to analyzing Cody's personal narrative. The museum's Buffalo Bill biography

notes that he was born in LeClaire, Iowa, in 1846; moved to Leavenworth, Kansas, as a child; left home at eleven to herd cattle and drive wagon trains; and tried his hand at fur trapping and gold mining before joining an early version of the Pony Express in 1860.

After the Civil War, "Cody scouted for the Army and gained the nickname 'Buffalo Bill' as a hunter providing meat for the railroad workers," it continues. But he wasn't universally acclaimed until "he met Ned Buntline, a dime novelist who transformed his life into a series of larger-than-life stories" that made him famous. In 1872, at age 26, he appeared in onstage dramas with Buntline before launching his own ensemble the next year. He and a revolving series of co-stars put on plays over the next ten years before the 1882 launch of Buffalo Bill's Wild West, in which Cody replicated many of his battles as an Army scout, using tribe members to portray opponents.

One bio passage concedes that the show "did little to educate audiences about the trauma American Indians faced from the American government." But it credits Buffalo Bill's Wild West for offering "an alternative way of life" that allowed Indigenous individuals "to earn money and represent their culture openly."

This overview leaves out plenty of Cody events that offend contemporary sensibilities, including his scalping of Cheyenne warrior Yellow Hair following Colonel George Custer's 1876 vanquishing at the Battle of Little Big Horn. (The scalp of a Crow combatant was part of an exhibit at the Buffalo Bill Museum until Friesen's stint as director; he helped repatriate it to the tribe.) But Friesen stresses that controversial elements aren't omitted from the museum itself. Rather, they're put into perspective in ways that he's tried to accomplish in books such as 2010's Buffalo Bill: Scout, Showman, Visionary and 2017's Lakota Performers in Europe: Their Culture and the Artifacts They Left Behind.

"When we're looking at any historical figure, I think it's important to understand the context in which they operated and judge them less by our standards today," Friesen recommends. "Yes, Buffalo Bill reflected some aspects of his time. But he advocated for equal rights for the American Indians, he said women should vote, and he spoke out on behalf of saving natural resources. If we look at him that way, I'd say he was ahead of his time."

Other scholars are less willing to give Cody a pass. In 2014's Sitting Bull, Buffalo Bill, and Native American Stereotypes, published by Texas Woman's University, authors Marcello Monterrosa and Rosemary Candelario contend that a photograph of Cody and Sioux Chief Sitting Bull is symbolic of innumerable sins against the Indigenous. "Buffalo Bill contributed to popular culture by introducing conflicting identities and harmful stereotypes of Native Americans as 'savages' but 'noble,' 'exotic' but 'uncivilized,' 'spiritual' but 'heathen,'" they write.

Indian Commission member Emerson endorses these opinions. "Buffalo Bill created, profited off of, and cemented in the American consciousness the image of the noble savage, the noble loser," he says. "He connected Natives to the American West as something to be conquered and tamed, bent to the will of the brave pioneer."

At the same time, Emerson doesn't cheer the impending shuttering of the Buffalo Bill gift shop. "My grandma and my mom would make dream catchers for the trading post — even though dream catchers have nothing to do with Diné [Navajo] culture — because that's what tourists were buying," he says. "Traders would bring Arab designs to weavers for Navajo rugs because they would sell better. I have heard that the gift shop bought and sold from Native artisans here in Denver, and losing a buyer isn't really something to celebrate."

Like the stars of yesterday and today, William F. Cody has his own page on the Internet Movie Database. IMDB also sports a list of the best films in which Cody appeared — mainly shorts that were made in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Buffalo Bill's Wild West Parade, in which New York City throngs gather to glimpse Cody and his cohorts, is on YouTube via the Library of Congress.

The website also lists 47 films or television series in which Cody was rendered by actors — a total that's almost certainly low. Among those to slip into Buffalo Bill's boots were Charlton Heston, Joel McCrea and Roy Rogers. But not all the depictions were laudatory. A cinematic compendium assembled by True West magazine observes that Cody was reincarnated "as a fanciful buffoon in Marco Ferreri’s 1974 anti-American satire Don’t Touch the White Woman! and in Robert Altman’s absurdist exposition on stardom and manifest destiny, Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull’s History Lesson," headlined by Paul Newman in 1976.

Paul Newman played William F. Cody in Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson.

Buffalo Bill and the Indians

Pulitzer Prize winner Larry McMurtry was less interested in focusing on Buffalo Bill's downturns, as evidenced by Cody's presence at the center of the 2005 nonfiction work The Colonel and Little Missie: Buffalo Bill, Annie Oakley, and the Beginnings of Superstardom in America. Bill got plunked into multiple McMurtry novels, too — most prominently 1990's Buffalo Girls, as well as 2006's Telegraph Days and 2014's The Last Kind Words Saloon.

But McMurtry died in 2021, and when younger film-goers hear of "Buffalo Bill," they're more likely to think of the serial killer in 1991's The Silence of the Lambs.

Some communities that have long used his image in promotions are already reducing that. Golden's annual Buffalo Bill Days began in the 1940s as a trail ride to the Lookout Mountain gravesite before turning into a family-friendly gathering in the downtown area. But the festival's 2024 iteration in Parfet Park revealed scant evidence of Western themes, with the exception of a single food truck, Rustler's Rooste, and a small sign on the information booth with the Buffalo Bill Days logo (a cowboy hat over a pair of revolvers). The live band on July 27 was Ronnie Raygun and the Big 80s, which delivered spot-on covers of new-wave favorites such as the Knack's "My Sharona."

If Golden's approach constitutes a trend, Cody, Wyoming is a big exception. The community of just over 10,000 a short drive from the main Eastern entrance to Yellowstone National Park is still enthusiastically embracing its namesake. The Buffalo Bill Dam is on the outskirts of town, and businesses such as Buffalo Bill's Irma Hotel and the Buffalo Bill Village motel and gift shop deploy his moniker.

And then there's the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, far and away Cody's most impressive establishment. Statues of Buffalo Bill — one of him riding a fast-moving horse, another in which he poses like a statesman — guard the exterior of a complex that houses five separate institutions (the Buffalo Bill Museum, the Plains Indian Museum, the Cody Firearms Museum, the Draper Natural History Museum and the Whitney Western Art Museum) and a gift shop of Bill Carle's dreams.

But there are no rubber tomahawks.

A perplexing question underpins the argument over the attractions near Buffalo Bill's Lookout Mountain burial place: Is what's left of him actually there? "The Mystery of Buffalo Bill Cody's Two Graves," a feature on the Town of Cody's website, suggests that his body's location isn't nearly as certain as it might seem.

The piece maintains that representatives of Denver and the Denver Post offered Cody's widow $10,000 to bury her husband on Lookout Mountain, "where they felt his grave could become a tourist attraction." Because she was in dire financial straits, Louisa accepted. But when two of Bill's Cody buddies found out about the deal, they allegedly cooked up a scheme with the local undertaker to swap his remains for those of a local ranch hand whose corpse had gone unclaimed. Together, they headed to Olinger Mortuary in Denver, where Cody had been stored while authorities waited for the ground to thaw enough to dig a grave, "and switched the body of Buffalo Bill with that of the unlucky look-alike." Shortly thereafter, he was planted on Cedar Mountain outside Cody in a location that's supposedly "a closely guarded secret."

When he's asked about the veracity of this yarn, Friesen replies cautiously. He doesn't want to anger any Cody residents, since he's stopping at the Center of the West on an upcoming tour for his latest book, Galloping Gourmet: Eating and Drinking With Buffalo Bill. (At 6 p.m. on August 23, he'll host "Buffalo Bill's Wild West Feast," highlighted by a dinner made up of victuals that would have been consumed by Cody's crew.) Hence the politeness of his response to the idea that Buffalo Bill is cooling his heels in Wyoming: "It is not true."

There's less doubt about whether the lights at the Buffalo Bill restaurant and gift shop will be switched off at year's end. That's bad news for employees, many of whom are international citizens in the U.S. on work permits who stay in housing on the Tepee's lower level. Carle, who lives on the building's upper floor, will lose his home, too.

Granted, H.W. Stewart still has several other ongoing ventures; the family handles three retail outlets in Grand Lake, Loveland's The Dam Store, and concessions for the Ozarks Amphitheater in Camden County, Missouri. But Carle will take a hefty financial hit, and he thinks Denver's on the same trajectory. On average, he says, the restaurant and gift shop generate $200,000 per year in tax revenue for Denver, and Echo Lake Lodge previously churned out about as much. With the Lodge contributing nothing since 2022, Carle believes Denver's combined shortfall could soon exceed $500,000 and grow from there.

Clark thinks those numbers are high; the city estimates restaurant-and-gift-shop tax revenues at $160,000 annually. And that doesn't take into account other costs. For instance, Denver and Carle split the bill for water, which is drawn from the pricey Lookout Mountain system. "It's 25 cents a gallon, so every time a toilet is flushed, it's a quarter," Carle says.

Given such expenses, Clark insists that the gravesite amenities aren't a profit engine for Denver. But since thousands visit the site, he wants to offer them a positive experience when they come for the museum and the view. True, port-a-lets will be substituted for the Tepee's bathroom facilities — definitely not an upgrade. But the city plans to have a food truck on site occasionally, as it's done at Echo Lake Lodge.

Because an assessment of the Lodge's condition is due by the end of 2024, Clark thinks Denver will soon have a better idea of next steps for that building. But there isn't a Tepee timeline: City troubleshooters are slated to look over the property next year to determine what must be done and whether a restaurant or gift shop can ever be cost-effective again.

Carle says he's going to spend the week leading up to December 31 serving customers instead of packing, so everything may not be out when the clock strikes midnight. He's already warned Denver reps about this likelihood, and Clark promises to be as understanding as possible in light of Carle's long-term relationship with the city.

In the meantime, a Tepee employee has started a petition to keep the restaurant and gift shop open; it's on paper at the gift shop but not online because "I'm not that sophisticated," Carle says. Nevertheless, he doesn't see a scenario where Parks & Rec leaders will change their mind.

"Every third customer we have asks, 'Are you really closing?'" he says. "And it's so frustrating not to be able to tell them why — because I don't know, either. But not one person has said, 'It's about time they got rid of you.' Not one."