The 49-year-old Lakewood native was working as a banker when he and his brother developed two apartment complexes just off of East Colfax Avenue a few years ago. But those projects pale in comparison to the one he’s working on now.

“Maybe you catch lightning in a bottle once or twice in your career,” Toerber says. “This seems like the opportunity to catch lightning in a bottle.”

Toerber is hoping that lightning will strike at the run-down but still operational All Inn Motel at 3105 East Colfax Avenue, which he wants to transform into a boutique hotel catering to both casual visitors to Denver and musicians performing at venues along Colfax. Nearby residents are eager to see Toerber’s hotel project become reality, since it will not only accommodate visiting relatives, but will include a restaurant that could become a neighborhood draw, as well as a pool that would be open to both hotel guests and neighbors.

But to bottle that lightning, Toerber will have to successfully navigate a complicated political situation and also secure financial backing in an area that investors have traditionally avoided. Because while Colfax Avenue has a way of enticing some people, it scares away others, including bankers.

Back in 1868, a dirt road cutting through then-ten-year-old Denver was named in honor of President Ulysses S. Grant’s vice president, Schuyler Colfax. As the city grew, so did Colfax. Eventually, it became the longest commercial street in America.

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, some of Denver’s richest citizens built mansions along Colfax; others established businesses along the avenue. Thanks to the city’s streetcar and, later, bus systems, it was easy to travel along Colfax, from Golden through Denver and into Aurora, or vice versa.

After World War II, Colfax was widened to accommodate the boom in automobile traffic. As part of the U.S. 40 Transcontinental Highway that stretched from the beaches of New Jersey to the coast of California, it became a major thoroughfare not just for metro Denver residents, but for travelers from across the country.

To cater to these visitors, developers began constructing motels, complete with catchy neon signs, along Colfax.

One such developer was Julius A. Buerger Sr. of the Buerger Brothers Supply Company, the region’s premier barber and beauty supply business. In 1959, Buerger finished construction of the Fountain Inn Motel at 3015 East Colfax.

“It was one of the earliest motels along East Colfax,” says Annie Levinsky, executive director of Historic Denver. “People drove across the country and would arrive in Denver on East Colfax.”

The 54-unit, four-story Fountain Inn Motel, valued at $1 million back then, was large for its time and place, with a distinctive white stone facade. Described as a “Deluxe Motor Hotel” and a “Home Away from Home,” it offered rooms outfitted with radios, TVs and music equipment, “making it a cutting-edge hospitality experience,” according to period advertisements.

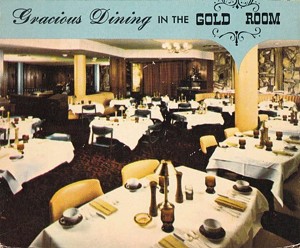

The Fountain Inn boasted a gigantic parking lot that accommodated not just motel guests, but Denver residents who wanted to eat at the fabulous Gold Room restaurant, the motel’s other big draw. There, patrons could get lobster fresh from the “frozen fjords of Iceland” as well as prime Colorado beef, all while sitting next to a wall paneled in 14-karat gold. Management of the Gold Room marketed the 100-plus-seat dining room to theater- and concert-goers stopping off for dinner before heading to a show downtown or at the nearby Bonfils Memorial Theatre, founded by Helen Bonfils, then the publisher of the Denver Post. (Today it’s part of the Lowenstein complex that houses the Tattered Cover.) The restaurant even offered rain checks for people who had to leave before dessert, so that they could come back after the show.

The who’s who of Denver would drop by the Gold Room to listen to live jazz piano, often played by Frank White, the man who later wrote the Denver Broncos’ official theme song, “Mighty Broncos.” Fans called in from across Colorado and even other states to listen to White’s performances at the Gold Room.

But as construction of Interstate 70 wrapped up in many parts of the West in the late ’60s, taking travelers far from Colfax, the street became irrelevant to many tourists.

“Without the tourism that came with the traffic, the decrease in activity materialized in a loss of business to many of the local establishments,” reads an application Toerber recently filed to add the All Inn to the National Register of Historic Places. “Colfax began into a downward spiral of decay as the price of real estate fell and tough economic times came down hard on the area.”

In 1969, the Gold Room shut down. Following a change in management, the restaurant reopened as an Italian spot, Stefanino’s, and the motel’s name was changed to the Executive Inn. Stefanino’s was short-lived, though, and became the Mexican restaurant Los Dos in 1973.

Los Dos, which was sometimes referred to in advertisements as Loco Joe’s Los Dos, marketed its “27 oz. of fun” margaritas and steak burritos. But while the margs were deep and the burritos filling, crime was also becoming big in the area, and there were often robberies in the parking lot.

Sometime during the late ’70s or early ’80s, the restaurant changed hands once more, becoming Miguel Ricardo’s, serving Mexican and Italian cuisine for breakfast, lunch and dinner, as well as jazz.

That combo didn’t last long. By mid-1983, the restaurant was for lease again, and the motel, which had been owned by a Canadian investment group, was bought for $750,000 by Hyo Pak, one of two entrepreneurial Korean immigrant brothers who purchased and managed motels throughout Denver.

But then Pak was stabbed to death while working at the Royal Host, another motel they owned, at 930 East Colfax. “Korean dies living his American dream” read a Denver Post headline.

“I’d really like to see East Colfax get civilized. It’s a jungle right now,” a former colleague of the murdered man told the paper.

Hyo Pak’s brother, Soo, took over ownership of the Executive Inn, and in the first few years was able “almost to break even,” according to a 1990 Rocky Mountain News article. But crime continued to be a problem both around and inside the motel. “My place is like the Vietnam war zone,” Soo Pak told the Rocky. He once had his face clawed by a prostitute he’d asked to leave his motel, he said.“People drove across the country and would arrive in Denver on East Colfax.”

tweet this

In 1998, Jong Min Kim, also a Korean immigrant, purchased the Executive Inn from the Pak family. They renamed the motel the All Inn.

The Kim family owned and managed the motel for a few years, until they became swamped by debt, which led to the property going into foreclosure.

In late 2005, Jesse Morreale, a Denver restaurateur and music promoter, purchased the All Inn. He kept the Kim family on to manage the motel. Ultimately, though, Morreale wanted to turn the place into a boutique hotel. “It’s the whole reason I did it. That was the whole point,” Morreale says.

But his first order of business was reopening the former Gold Room.

Debuting in August 2006, the 1970s-themed Rockbar — named both for the building’s facade and the rock-band-themed booths in the bar — was an immediate hit with hipsters and lovers of gritty Colfax nightlife.

“You just knew it was cool. The dance floor was set up in a way that you just kind of disappeared into it. You stepped into this mass that was rocking, and the ceiling was low and dark,” recalls Jonny Barber, founder of the Colfax Museum. “It had that vibe where you could just completely be yourself and go for it. Nobody really cared or could hardly even see you. I had some of the greatest times of my life there.”

But Morreale cared what was going on outside, too; he wanted to stop the slide of this part of Colfax. “The parking lot was empty and it was dark. There were no lights. There was bad shit happening there,” recalls Morreale, who remembers thinking, “We’re going to get this bar open, do food and music, and use it as an anchor to get real people there.”

Rockbar’s first year brought an energy that the area hadn’t seen in years, and snagged Best New Bar honors in Westword’s Best of Denver edition in 2007. “Rockbar could inspire a confirmed teetotaler to do a swan dive off the wagon within ten minutes of walking through the door,” the award noted. “Rockbar is the ideal place to relive your wasted youth.”

In 2008, when the Democratic National Convention came to town, Morreale successfully billed the Rockbar as the BarackBar, and ended up attracting such celebrities as Spike Lee, Anne Hathaway and Susan Sarandon. There was even a John McCain piñata for bar-goers to whack.

But while nights at Rockbar might have been great for patrons, neighbors complained that the area had gotten a little too lively.

Rockbar’s liquor and cabaret licenses were set to expire in August 2012, so Morreale applied for renewal. But the city denied the application.

Morreale fought the city’s decision. “There was really no reason for it, because there were no police calls, no complaints; we had no liquor violations,” Morreale says.

The Denver Department of Excise and Licenses held an administrative hearing, where city officials noted that the bar wasn’t getting enough of its money from food sales to qualify for its license. Heads of registered neighborhood organizations testified that Rockbar was having a negative effect on the safety and welfare of the area, and police representatives detailed the crimes that had happened in the vicinity.

Morreale contested the claims, but he lost the case, and the Rockbar shut down just a few months later. At the time, Morreale was also battling the city over his First Avenue Hotel property on Broadway, which housed two of his restaurants. “You can’t ignore what happened with the building at First and Broadway and what they did with Rockbar,” Morreale says.

The First Avenue property was declared off limits by the city, and Morreale eventually lost it in bankruptcy. It was subsequently auctioned off, and is now an affordable-housing development that plans to add restaurants on the first floor.

But while the First Avenue Hotel — now known as the Quayle — has made a comeback, the All Inn has continued to attract negative attention.

Denver Police Department records show that there were 92 calls for service at the All Inn in 2019. Police responded to calls related to domestic violence, sexual assault, suicide attempts and stabbings, among other reported crimes.

The Denver Department of Public Health and Environment has also received complaints from All Inn guests that the department must investigate. Most often, those complaints are about bedbugs.

But the city can’t blame Morreale for those problems: He was never able to reopen Rockbar and wound up losing the All Inn property in bankruptcy. Ultimately, it, too, was auctioned off.

Brian Toerber started dabbling in development in 2011. Part of his motivation to get into real estate was timing, since the country was coming out of the recession. But the recent death of his mother was the driving factor for Toerber, who says that her passing was the catalyst for starting to take risks.

While still working full-time in banking, Toerber and his brother invested in two apartment building projects just off Colfax. It wasn’t the charm of Colfax that drew him to the area, just the opportunity. “Honestly, I remember it being hookers and blow back in the ’80s,” Toerber says.“The first building just so happened to be on East Colfax. It could’ve been anywhere.”

In 2016, Toerber was thinking of expanding his development portfolio when he found out that the All Inn was going to be sold at auction. He bid $3.55 million for the property, and got it.

Toerber’s original idea was to turn the All Inn into a micro-unit apartment complex, similar to what he and his brother had done with Detroit, one of their apartment buildings. But first, he wanted to get buy-in from neighbors and the Denver City Council representative for that part of town.

In May 2016, Toerber met with then-councilman Albus Brooks over coffee and told him his plan.

“I’m looking to do some affordable housing, something attainable,” Toerber recalls saying. “I’ll clean up the units, rent it out, and lease it out as is.”

Affordable housing is sorely needed throughout Denver, and along certain parts of East Colfax, where longtime residents are being displaced, the need is particularly acute. Even so, neighbors of the All Inn saw a more pressing need.

“The neighborhood really was pushing for a boutique hotel,” remembers Brooks. “There’s not a hotel in the area.

A lot of these homes in that neighborhood don’t have a guest room. Grandparents coming to visit kids needed a place to stay.”

This was the first time Toerber had even thought about creating a hotel. It would give him a chance to activate the ground-floor space, and also get rid of some street-side blight.

“Everybody in our neighborhood, we want to see these rundown buildings turn into new coffee shops, new retail spaces. We want a vibrant life for this part of Colfax. Right now, that area is kind of lifeless,” says Emily Clark, president of the South City Park Neighborhood Association.

While the Kim family continued to run the All Inn, Toerber explored the hotel possibility.

Matt LaBarge, the owner of Sputnik, a bar on Broadway, who also used to own Lost Lake Lounge on East Colfax, had gone to the All Inn auction to observe the action, but not to bid. He’d wanted to turn the All Inn into a boutique hotel for years, and eventually shared some of his thoughts with Toerber after they became friends.

“I thought that could be a pretty fun project in a great area,” LaBarge says. “I helped him brainstorm some ideas for the place and things that I was thinking of, and what would work for the space.”

Among other things, LaBarge suggested that Toerber go down to Austin and see the South Congress Hotel. Another friend had the same advice.

So in June 2016, Toerber called up the team behind the South Congress: New Waterloo, a hospitality management and development company based in Austin.

Toerber told them about the property on East Colfax Avenue, and said he was thinking of pursuing a boutique hotel project there.

Bart Knaggs, the CEO, was intrigued, as was Patrick Jeffers, who just happened to know Denver: He’d lived in the city in the late ’90s and was a Denver Bronco for two seasons, playing on the team when it won the Super Bowl against the Green Bay Packers in January 1998. They told Toerber that they’d be in Colorado for another project in Steamboat Springs; Toerber suggested they meet at the All Inn.

But that August, as Knaggs and Jeffers drove up to the motel, they started having second thoughts. “We were pulling up, and I’m like, ‘Oh, no. What the hell,’” recalls Knaggs.

“Stark concrete is all you see,” he recalls. “The streetscape and pallor of lingering people and drapes swaying through the open windows just conveys a sense of sadness and lack of vitality to the place. The trees in the neighborhoods and the storefronts down the street are absent. I felt a place that had been forgotten, neglected and no longer imbued with optimism. It just lacked life. So seeing it at first blush, it felt like a big concrete mass without a soul.”“I felt a place that had been forgotten, neglected and no longer imbued with optimism.”

tweet this

In the car that day, Knaggs tried to bail at the last moment. “I’m like, ‘Dude, let’s keep driving, let’s keep driving.’ Instead, there was Brian standing outside of his car, waving at us,” he says. “And Patrick was like, ‘We’re busted.’”

So they got out and toured the property with Toerber, and then the three walked along Colfax to grab a pizza slice at Fat Sully’s. During that walk, Knaggs and Jeffers realized that there was something magical about Colfax. The street had an undeniable grittiness, but also an appealing authenticity.

“Colfax isn’t blighted. Our site is the blight,” Knaggs explains. “It was a powerful little insight when you realize we’re going to fix the problem by doing this site. The problem’s not the neighborhood. We’re the problem.”

From this visit and that sentiment, momentum for the hotel project began to build.

Denver is in the middle of a hotel-building boom, with a dozen new boutique hotels planned for LoHi, RiNo and downtown in the next two years; a few big, branded hotel projects are also on the books. “Denver was already on our radar,” says Jeffers. “We’re looking for true neighborhood independent hotel locations.”

A few weeks later, Toerber went to Austin to check out the South Congress.

The hotel is in a part of town that once had the grit you find today on East Colfax, says Knaggs. On an empty lot, New Waterloo built a hotel with 71 guest rooms, ten suites, a rooftop pool, and a first floor with three restaurants, a coffee shop and some retail stores. Since it opened in the fall of 2015, the New Congress has become both a boutique hotel and a neighborhood gathering place.

Toerber thought something similar would work on East Colfax, but he was worried about its financial feasibility. “I just didn’t see making money on this deal,” he remembers. So instead of pursuing the hotel idea, Toerber and the New Waterloo team decided to revisit the idea of putting affordable housing on the property.

For ten months, Toerber pursued funding from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. During this time, he left his bank job to focus full-time on development.

He pitched a project that would have involved demolishing the All Inn and creating 212 affordable units on the site. But that path turned out to be a dead end. “HUD never got comfortable,” Toerber remembers. HUD officials felt that the units, 475 to 550 square feet each, would be too small, and that the rent, $1,100 to $1,275, would be too high.

“We were pretty deflated that they didn’t believe in the vision we fully believed in,” he adds.

After months had passed, Toerber finally called up Knaggs and Jeffers and said he was ready to pursue the boutique hotel idea. “Hey, I think this is a perfect fit for you guys,” he recalls telling them. “They said, ‘Hell, yeah. We love that site. We’re coming back to town. Let’s solve it.’”

Together they came up with specs for a boutique hotel that would be activated with a cafe, restaurant, pool and bar on the ground floor, a place that would be popular both with neighbors and hip visitors to Denver. They felt confident in their vision, and thought the project could eventually run in the black.

“The market will reward you if you put your faith out there first,” Knaggs says.

But in order to get a hotel off the ground, they needed money as well as faith. And that quickly became an issue. Over forty lenders, most of them banks, took a look at the proposal and passed.

Toerber thinks that banks shied away because the hotel was small and wasn’t a branded property. But they also were concerned about the stigma of East Colfax,

Just one lender, Stonebriar Commercial Finance, decided to pursue underwriting the redevelopment. Toerber says they should hear back any day about whether and how much Stonebriar will loan the project.

Toerber has also applied for the property to be declared historic at both the state and federal levels so that the redevelopment project can potentially qualify for state and federal tax credits of up to 20 percent. His researcher thinks that the All Inn’s days as the Fountain Inn would qualify it as historic.

But the hotel still needs more support to be financially viable. And while financial institutions are usually the go-to source for funding projects like this, there are other ways to get money for development projects in Denver.

The Denver Urban Renewal Authority works with private developers taking on projects in blighted parts of town and helps with funding...if Denver City Council approves the deal.

Last year, only one such project was approved. A private developer will receive close to $25 million earmarked from projected real estate tax revenue to help subsidize an urban redevelopment project that will put hundreds of homes — including affordable units — as well as businesses at 4201 East Arkansas Avenue, the site of the Colorado Department of Transportation’s former headquarters.

When considering whether a project can qualify for DURA support, staffers look for elements of blight, which are defined in state law and include things like deteriorating structure, unsanitary conditions and substantial physical underutilization.

“It’s really clear that the current state of the property is not consistent with what the city would like to see or what the community would like to see,” says DURA Executive Director Tracy Huggins, who’s walked by the All Inn.

In order for DURA to consider underwriting a project, it needs a letter of support from a Denver government official. Typically, that letter comes from the city council representative who represents the district the planned project is in. For the All Inn, that was Brooks, who’d already been effusive about his support for a boutique hotel on the site.

But then in June 2019, Brooks was defeated in a runoff election for his seat by Candi CdeBaca, a social worker and progressive community organizer. Since taking office, CdeBaca has been challenging the status quo of Denver politics and representing communities that she believes have been ignored by city officials.

Above all, she thinks those communities want affordable housing.

“Our priority is about affordable housing. I’ve been talking with [Brian]. A boutique hotel doesn’t quite fit that,” says Lisa Calderón, CdeBaca’s chief of staff.

But neighbors have reached out to CdeBaca’s office, imploring the councilwoman to support Toerber’s bid for DURA funding. “You have this eyesore that does nothing but bring the neighborhood down,” explains Timothy Swanson, who lives close to the All Inn. “We all want to see Brian get his financing from the city and then get his other financing and get this project moving. It’s been several years since his group acquired it.”

Clark, the president of the South City Park Neighborhood Association, says that neighbors are overwhelmingly in favor of the project. Clark herself loves the idea, especially after visiting South Congress Hotel in Austin. “It’s beautifully done,” she says. “All of the design, the shops, the restaurant. It would be really amazing for our side of Colfax to get a property like that.”

But CdeBaca hasn’t budged.

“We’ve sent letters to her in support of it and they don’t seem to be helping, which is unfortunate, since she’s supposed to be our voice for things like that, versus her personal agenda,” Clark notes.

“We’re not just building for who’s there currently,” Calderón responds. “We’re also thinking about who needs to live there but can’t afford to.”

Toerber has done his best to allay these concerns, even purchasing a motel on West Colfax last May so that current All Inn tenants have an option when construction starts. The Kims are running that spot, too.

“These motels, they range from overnight guests to weekly guests to monthly guests,” Toerber explains. “It’s the monthly guests that we really want to find alternative housing for.”

Without a guarantee of support from the district’s representative, Toerber had to search for a new solution.

Although it’s unusual, occasionally DURA will receive a letter of support from an official with the Mayor’s office.

So Toerber reached out to the Hancock administration.

Toerber was invited to present his proposal to various department heads, including Laura Aldrete, the head of Community Planning and Development, and Eulois Cleckley, the head of the Department of Transportation and Infrastructure. Toerber ended up winning them over, and the Hancock administration decided to support his DURA application.“Denver was already on our radar. We’re looking for true neighborhood independent hotel locations.”

tweet this

Joshua Laipply, the chief project officer for the city, wrote Denver’s letter of support to DURA. “I think it’s a good balance of trying to fit economic development and revitalization of an area without adding a whole bunch of new development, which sometimes people are hesitant about,” Laipply says. “This one just felt good.”

DURA is continuing to study the project’s finances, to determine what the city can offer in support; Toerber estimates that the total cost of the development will be $28 million. A few months from now, DURA will present its All Inn proposal to city council for approval.

In the meantime, Toerber, Knaggs and their team are already moving ahead on what they envision offering at the new hotel, which they hope to have open by Christmas 2021.

There will be 81 rooms, 54 of which will be redesigned versions of the existing All Inn units and 27 of which will be located in a new four-story building that they’ll construct on the property. There will be a pool next to a part-outdoor, part-indoor lounge. There will also be a restaurant and bar that are open all day, as well as a cafe.

The parking lot will remain large, because Toerber and Knaggs hope to attract Denver residents as well as tourists. But there’s a particular kind of traveler that really intrigues them.

“We’ll be able to park tour buses on site,” Knaggs says.

They’re hoping that bands performing at the Ogden, Fillmore and Bluebird will drop off their stuff at the hotel and then head over to the venue to perform. Once the show is over, they’ll return to the All Inn and enjoy the Colfax vibe.

“I think it’s a fabulous idea,” says Don Strasburg, co-president of Rocky Mountain AEG, which promotes shows at the Ogden and the Bluebird. “It’s well located, and if the rooms are nice and there’s accommodations for touring parties, it should work really nicely.”

But one of the true draws will be what was once considered a drawback: its location. Colfax is “like a broken-in leather jacket that just doesn’t ever go out of style,” says Knaggs. “Trends may come and go, but you’re just never going to get rid of that thing.”

Although the ideas are new, the new owners won’t be changing the motel’s name. Toerber plans to keep it the All Inn, in homage to the long route he and his partners have taken on Colfax.

“I do think it’s symbolic of how much we’ve committed to this project,” says Toerber. “We literally went all in on the All Inn.”

For more about the All Inn, view the slideshow Street Dreams: Can the All Inn Be Saved?