On the last Tuesday of August, Byron Shaw and Corbin Hughes kept walking around a fence that separated an apartment complex parking lot from a field near Expo Park in Aurora, looking for a way in.

The two outreach workers with Mile High Behavioral Healthcare, a local nonprofit that specializes in working with the homeless, were trying to reach a tent that had been set up in the field. Neighbors had called Aurora officials to let them know that three children and a father were camping out in the tent; the city had contacted Mile High Behavioral Healthcare.

Shaw and Hughes were there to see if they could help. But when they finally reached the tent, a young man came over from by the fence and yelled at them to get away.

After they told the man why they were there, his temper cooled; he explained that he was a friend of the children’s father and was babysitting the three kids while the father was working. Right on cue, the father returned, having finished his shift for the day.

He told Shaw and Hughes that the family had been living in an apartment in the nearby complex for two years, but had recently been evicted.

The two outreach workers gave the family water, snacks and clean socks.

“We saw a raccoon,” one of the children, a boy no older than five, told Hughes excitedly.

Then Shaw made an offer: He’d come back later in the day and drive the family over to Comitis Crisis Center, the emergency shelter in Aurora, so that they could shower and change their clothes. They might also be able to get linked up with emergency shelter on the family floor at Comitis, with the possibility of staying up to two years.

“That’s good news if he accepts. It’s his choice. Hopefully, he accepts and gets his kids inside,” said Shaw. (He later confirmed that the family had indeed taken him up on the offer for emergency housing.)

Later that morning, Shaw and Hughes visited another park where other people were staying. And they met with still more homeless individuals camped out in RVs in an Aurora parking lot.

Downtown Denver isn’t the only part of the metro area that’s seeing a surge in homelessness, with encampments large and small springing up in unlikely places.

By the latest count, Aurora has at least 427 people inside city limits who are experiencing homelessness. Service providers are trying to reach them where they live, rather than requiring them to travel elsewhere to find help.

But while homelessness is a metro-wide issue, one that’s only been increasing in scope during the pandemic, few municipalities are stepping up to address the challenge, letting cities like Denver and Aurora take the lead...and pay the cost.

It might take leadership at the state level to change that.

John Parvensky, who has served as executive director for the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless since 1985, says that the failure of service providers and elected officials to build a regional effort to address homelessness at the scale that’s necessary is one of the biggest disappointments in his work.

“There’s been a lot of talk and not a lot of action. There doesn’t seem to be a same level of commitment to the issue,” Parvensky says, adding that most metro municipalities seem content to let service providers and the largest cities handle the burden.

Plenty of regional meetings and projects have focused on tackling homelessness over the years, but they’ve led “more to nonprofit coordination” than to “actual city and county coordination,” according to Parvensky. The Denver Regional Council of Governments, for example, has a standing offer out to local governments to facilitate a conversation on how to address homelessness on a regional basis. But that offer has yet to be accepted.

Denver, Boulder and Aurora governments have done their fair share in recent years. Mayor Michael Hancock allocated close to $100 million for homelessness and affordable housing in Denver’s 2020 budget, a massive increase over the approximately $25 million that the Hickenlooper administration dedicated to these two priorities in 2010. Aurora budgeted close to $26 million for homelessness and housing matters in 2020. With federal COVID aid dollars added, Aurora’s total budget for these issues totals around $34.5 million.

While experts agree that all of these dollars combined are still not enough to fully address homelessness in Colorado’s largest and third-largest cities, some other municipalities in the metro area allocated next to nothing for services for the homeless. Centennial, for instance, budgets no money for housing and homelessness, instead looking to Arapahoe County to provide those services. But Arapahoe County’s budget earmarks just under $800,000 for affordable housing and homelessness annually. Douglas County, meanwhile, has spent a little over $25,000 this year to “assist the homeless in Douglas County with housing,” by providing hotel vouchers, case management and transitional housing, according to a county spokesperson.

“There’s a fear among certain communities that by acknowledging that homelessness exists and by providing services, that’s somehow going to affect property values,” says Matt Meyer, executive director of the Metro Denver Homelessness Initiative. “And we just haven’t seen that.”

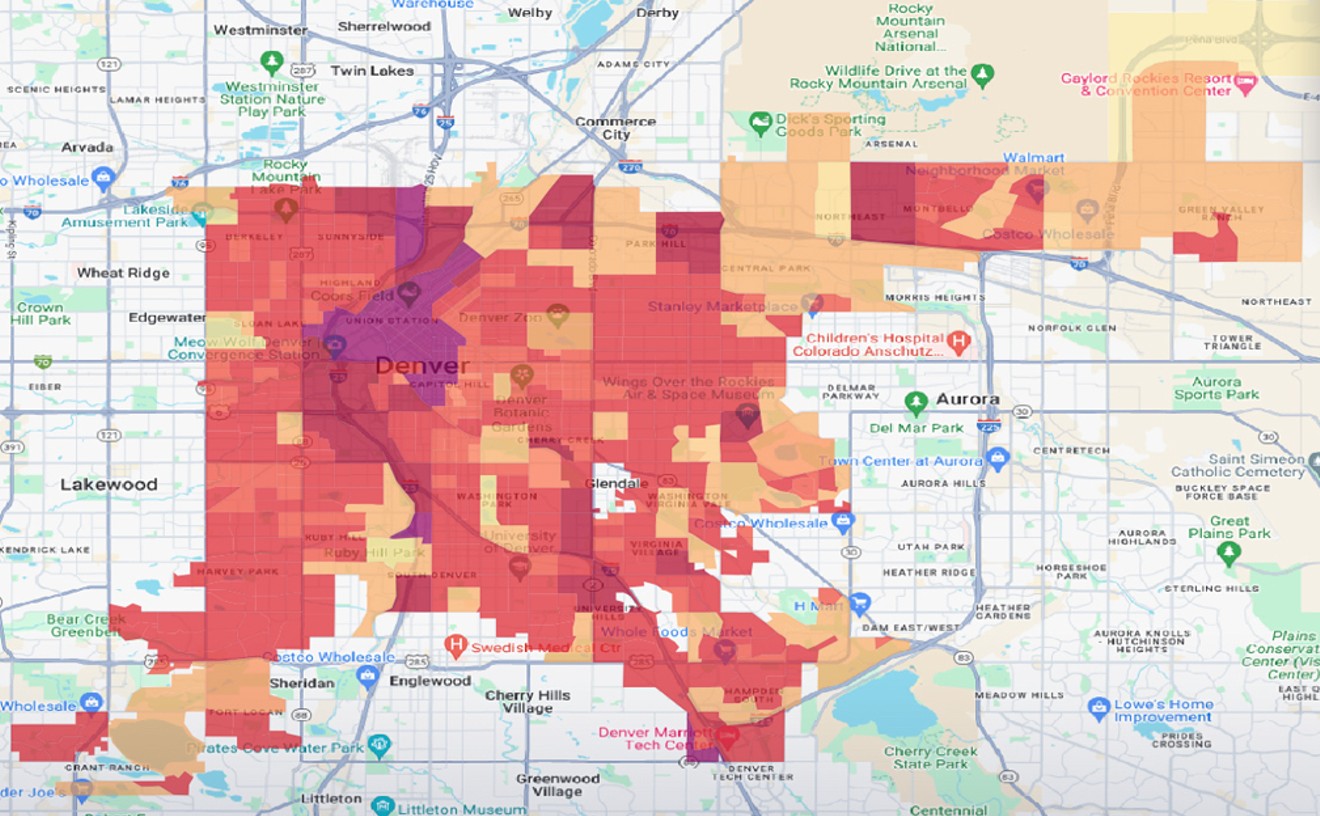

MDHI conducts an annual Point in Time Count that attempts to document the number of individuals experiencing homelessness in the region. The 2020 Point in Time Count, conducted in January, identified 6,104 homeless individuals either staying in shelters or living in unsheltered settings in Denver, Jefferson, Douglas, Adams, Arapahoe, Broomfield and Boulder counties. Of that total, 4,171 of the individuals were in Denver. The numbers for Denver and the metro area have been rising since 2017 — and the January count was conducted before the coronavirus pandemic hit.

Of all the municipalities in the seven-county region, Denver has by far the widest array of services for homeless individuals; as the hub of the area, it also has the majority of the area’s homeless population. Over the past few months, large encampments were established in several parts of central Denver, but recent sweeps of camps in Lincoln Park in front of the Capitol and outside of Morey Middle School in the Capitol Hill neighborhood pushed many individuals into other parts of the city…and outside of the city.

On the last Friday of August, Ashley Loveless, another outreach worker with Mile High Behavioral Healthcare, walked from one RV and tent to another at a large encampment located on South Platte River Drive in Denver, right on the border with Englewood. The encampment had grown by 30 or 40 percent since the pandemic began, according to Loveless, who was there with two other colleagues to provide those staying there with items like Narcan, sterile drug cookers, condoms and water bottles, and also to potentially connect them with various services and government benefits.

Unlike the more controversial encampments in central Denver, this spot on the Platte River wasn’t located particularly close to homes or businesses. It had been allowed to operate mostly undisturbed, and had even set up its own bathroom and communal kitchen. But in mid-September, the City of Denver, with assistance from Englewood, swept the encampment, citing fire and public-health concerns; its occupants spread out, some perhaps heading farther into the suburbs. “They just relocate,” says Loveless. “They don’t go far, since there’s really nowhere for them to go.”

Before the pandemic, the MDHI tally counted around 2,000 homeless individuals living outside of Denver. That strengthens Denver’s argument for seeing services distributed more widely through the region.

“What I hope we can do as a community together is, if someone is facing a housing crisis, that they are able to get help to navigate that crisis in the community in which they live. That they don’t have to go away from the community assets that they know, the neighbors they know, the schools and faith communities that they’re connected to,” says Britta Fisher, executive director of Denver’s Department of Housing Stability. Currently, she notes, having to relocate because services aren’t nearby is “part of the trauma of experiencing homelessness.”

In her view, a key part of the problem is that some residents of the metro region and the politicians they elect to office still believe homelessness is an issue outside of their community, and not something that they have to deal with.

But while a small minority of those experiencing homelessness are from out of state, the majority are from the metro region. “These aren’t people coming from far, far away,” says Fisher. “As long as it persists in people’s minds that this is from someplace else, we don’t take ownership of it as a community.”

The pandemic may finally change that, by pushing the state to tackle homelessness at a regional level.

To allow for social distancing to help prevent the spread of COVID-19, the city set up two temporary shelters, one at the Denver Coliseum, the other at the National Western Center. “We conducted a one-time survey during one of the meal servings at the National Western Center,” says Derek Woodbury, a spokesperson for the Department of Housing Stability. “Of the 323 people surveyed at NWC, 181 (56 percent) reported that they stayed in a location in Denver before coming to NWC. Additionally, 62 people (19.2 percent) came from other places in the seven-county metro Denver region. In total, that adds up to 243 people (75.2 percent) who came to NWC from the metro.”

The need is great both inside and outside Denver city limits, and more jurisdictions are beginning to recognize that.

“I’ve been really encouraged during the pandemic, how it has been brought to the forefront of how we need to increase communication and collaboration across jurisdictional lines,” says Fisher.

As part of Colorado’s emergency response to the pandemic, state officials recently formed the State Homeless Task Force, which has the purpose of “determining needs and gaps within the state, and filling those with local, state or federal resources” and coordinating with local communities for “information and guidance, resources and coordination, and technical assistance,” according to Brett McPherson, a spokesperson for the Colorado Department of Local Affairs.

“The pandemic has brought up a lot of the cracks and weaknesses in the homeless response system, so I think there is opportunity for us to do broader-based planning. I think the will is there,” says Meyer, who is part of the task force. The group’s membership includes representatives of both state and local entities focused on homelessness; they’ve been working primarily on daily and weekly efforts to navigate housing and homelessness needs during the pandemic. In the near future, the task force will produce reports that highlight regional capacities for cold weather emergency shelter and how to better communicate the existence of resources, according to Fisher, who serves on the task force.

“I hope we don’t lose this muscle memory. This is the coordination and collaboration we need to continue, and I think we can,” she adds. “The pandemic put a focus on immediate urgent public-health issues, but they also help us to work on this more persistent crisis that we’ve already been facing.”

Still, the task force isn’t nearly as collaborative as some providers would like it to be: The only metro municipality represented is Denver, and the only other county government involved is Summit County. So while the state and service providers are displaying better coordination during the pandemic, many jurisdictions simply aren’t part of the conversation.

Parvensky is counting on the state to continue wrangling people together to make sure that every municipality is involved in addressing the regional issue of homelessness.

“It really does take political will from the top to make something like that happen,” he says.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "leaderboardInlineContent",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "tower",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

}

]