Denver Police Chief Ron Thomas, who describes Clemmons as a longtime friend, was there; so were Armando Saldate, head of Denver’s Department of Public Safety; Liz Castle, Denver’s independent monitor; members of the city’s Citizen Oversight Board; and community civil rights leader Lisa Calderón, a two-time candidate for mayor.

Clemmons helped establish the Denver Office of the Independent Monitor in 2004 before heading to Duke University to get her Ph.D.; at this event at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies, which houses the Scrivner Institute, she shared results of research completed from 2017 to 2020. Her study focused on what residents of neighborhoods that had been disenfranchised from police to the point of "legal cynicism" — a term used by researchers to describe when people believe law enforcement is “illegitimate, unresponsive and ill-equipped to ensure public safety” — wanted out of their police departments.

“On one hand, there's research that says Black Americans are more likely to avoid police or to want to keep their distance, but on the other hand, there's this public polling showing the majority of African Americans want police protection,” Clemmons explained. “I'm entering the debates about whether African Americans living in areas challenged by high crime levels want to distance from police or whether they want to be closer to them.”

Clemmons used Durham, North Carolina, as her case study, along with British Bengali Muslims living in London. She found many surprising similarities between the two groups through 52 interviews with 18- to 29-year-old men living in high-crime, heavily policed neighborhoods from 2017 to 2020.

Two-thirds of those men had been on the receiving end of a crime, with a little over half the victim of a violent crime. Over half had also witnessed a violent crime, and 38 percent of the American participants had been shot at least once. Clemmons found that 76 percent of them held views consistent with legal cynicism.

“Americans and Brits criticize police as ineffective against criminals whilst also violating people's constitutional and human rights and treating them too often with bias, disrespect and excessive force,” she said. “The men shared scores of stories with me that they characterized as infuriating and unbelievable stories in which they were either physically hurt and/or humiliated by police.”

The interviewees were worried about the world becoming unsafe, and felt that they couldn’t protect their loved ones; they were particularly concerned about the next generation. “This was a cry for children,” Clemmons said. “I mean, these were 18- to 29-year-old men — you would think they were in their seventies, the way they were talking about this next generation and their concerns.”

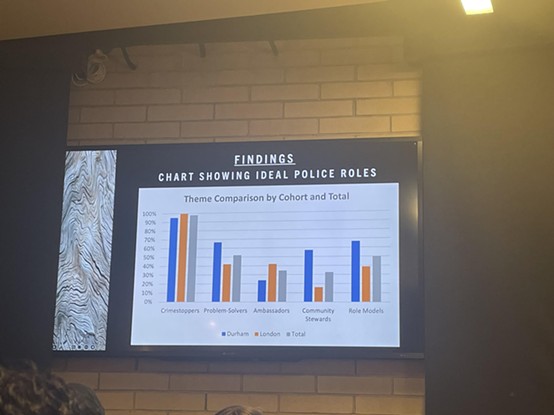

Yet across the board and despite their legal cynicism, they saw police as integral to helping reverse crime trends and creating a safer world for the next generation. They identified five qualities that an ideal police force should embody. The first was being crime stoppers: Participants said they think some people should go to jail, and if police could prevent crimes and catch criminals without harassing community members, that would be an invaluable service. Second, research participants said police should be problem solvers who could help resolve short-term disputes and collaborate on solutions to complex problems in the areas they serve. Though more Londoners wanted police to be ambassadors, with 42 percent identifying that role for officers compared to 24 percent of Americans, they all wanted officers to serve as educators about safety.

On the other hand, around two-thirds of Americans compared to 16 percent of Brits said one of their ideal roles for police was as community stewards. “I would tell the person in power, whoever it is, to deploy the police officers to go to the community, spend more time in the community, eat their food and share the sun with those people and build a relationship,” Clemmons said, sharing a quote from one of her participants.

They also suggested that officers collaborate on service projects with the community, hold events such as parades in areas that had experienced violent crime, and even financially restore people who had been subject to fines and fees from law enforcement.

Castle asked Clemmons if research participants felt the police force should reflect the community in terms of race, and if they preferred that officers come from within the community they oversee.

“They still wanted the proper vetting regardless of the person,” Clemmons answered. “They wanted accountability regardless of the person, but they did want police forces to be diverse. … They also wanted them to be culturally competent, and they wanted more hiring locally.”

Even if officers weren’t recruited locally, participants wanted them to take action to show they respected and cared for the community by doing things like “fixing flat tires and help grandmas” to build trust, she said.

And finally, participants wanted police to be role models. “Despite their myriad complaints about officers, most participants viewed them as an under-leveraged collective resource for good,” Clemmons noted.

After conducting her research, Clemmons had compiled suggestions for the Durham Police Department, some of which she shared with the Denver group. One suggestion was to clarify and limit behaviors around touching and pointing weapons through increased training, along with oversight after officers draw or discharge weapons.

She also suggested officers spend one shift per week filling a community service need. And she highlighted a suggestion that communities be allowed to request the reassignment of an officer from their area if there was evidence suggesting that officer’s actions were harmful. However, she also noted that because of police union rules, she was still workshopping how that policy could be implemented.

To help build trust, she recommended follow-up measures to let people know when crimes they report are solved or what police are doing to solve crimes.

Ajenai Clemmons has long worked in Denver, and now she's back.

Josef Korbel School of International Studies

“It can't be just the community being vulnerable and admitting that it's not every officer, but then the departments are not honest about the fact that they have issues that they need to address,” Clemmons said. “It has to be both sides, coming with that vulnerability, with that honesty and integrity, and with that respect for one another and respect for one another's intelligence.”

Calderón, who's been working with Clemmons for decades on questions of community safety, asked if people said they wanted more police interaction merely because they weren’t presented with any alternative options to achieve safety.

According to Clemmons, participants expressed support for measures other than policing, such as economic stimulation, transportation reforms and affordable housing, that would help improve their lives and keep them safe. In particular, they wanted safe spaces for youth to go and ways for them to make money so that they wouldn’t be tempted by gangs or drawn in by human traffickers. But most of those surveyed definitely wanted police to stick around, she emphasized.

“It's important to consider that, for people who are political activists, if they want to take that away or they want to create alternatives, you're going to have to work extremely hard to convince people,” Clemmons added.

A few in the room, including Calderón, asked Clemmons if she thought her findings would be different if the research had been conducted after the death of George Floyd in May 2020 and the mass movement to reform or abolish police that followed.

Clemmons responded that after similar events in the past, people had stopped calling the police — but eventually, those numbers rebounded. Such events can also make people want police to protect them just as much as they protect others, she added.

“I'm an American,” Clemmons suggested some might think after seeing someone of their race mistreated by police while those of other races were protected. “I deserve this. I'm owed this. This is my birthright. I should be able to be secure in my person. I should be able to walk the street in peace. I should be able to leave my things there and they're there when I get back. Even identity and citizenship get tied up into people's roles that they idealize for police to have in their lives.”