Johnston announced the Denver Asylum Seekers Program (DASP) last month as part of his new migrant response plan intended to cut expenses. Per the new plan, shelter services to migrants will be ramped down, but the city is now offering six months' rent and job training. The program hinges on the idea of setting up migrants for long-term stability and success by walking them through the asylum process, according to the city.

The new asylum program is "one component" of Johnston's current $90 million migrant plan, with $25 million of it spent already, according to Denver Human Services spokesperson Jon Ewing. That budget also pays for hotels, food and bus tickets as Texas state and local governments buss migrants to Denver.

About 42,000 migrants have arrived in Denver since December 2022, according to the mayor's office, with about half of them thought to still be in the metro area. Johnston's administration estimates that the city has helped more than 1,800 migrants attain work permits — which is the focus of DASP.

Migrants in DASP get six months of rent paid at an apartment, job training that matches skills they already have, and a debit card to pay for food while they apply for asylum and wait to attain a work permit, which usually takes around five months. And with a donation of 700 Dell laptops from AT&T, every adult will be able to have their own computer.

Initially, the program would only take 1,000 migrants at a time, but only about 800 participants were identified as candidates after the city and nonprofits found that fewer migrants were seeking asylum than originally thought. That's because most migrants that the city talked to while recruiting for DASP are already eligible for work permits after scheduling immigration proceedings through U.S Customs and Border Protection.

Currently, 540 migrants are enrolled in DASP, but the city is expecting to enroll more than 700 by the end of the week, with about 100 more coming in during the following weeks.

To recruit, the city's Newcomer Services Program and nonprofits like Papagayo and ViVe Wellness signed up migrants in shelters or rental-assisted living who might qualify. They looked for migrants with stories that show real fear of being persecuted in their home country — a qualification for asylum — which is common for immigrants from Venezuela.

Migrants are offered a chance to come to the Mullen Home, 3629 West 29th Avenue, to sign up for DASP, but they're also informed about the asylum process and the program they're entering. Since Thursday, May 9, the city has taken these first steps to get DASP going, with between 100 to 200 recruited migrants showing up each day to begin the program. A couple more days of enrollment are scheduled for the week, and then the city will finish DASP registration with the exception of a few make-up dates.

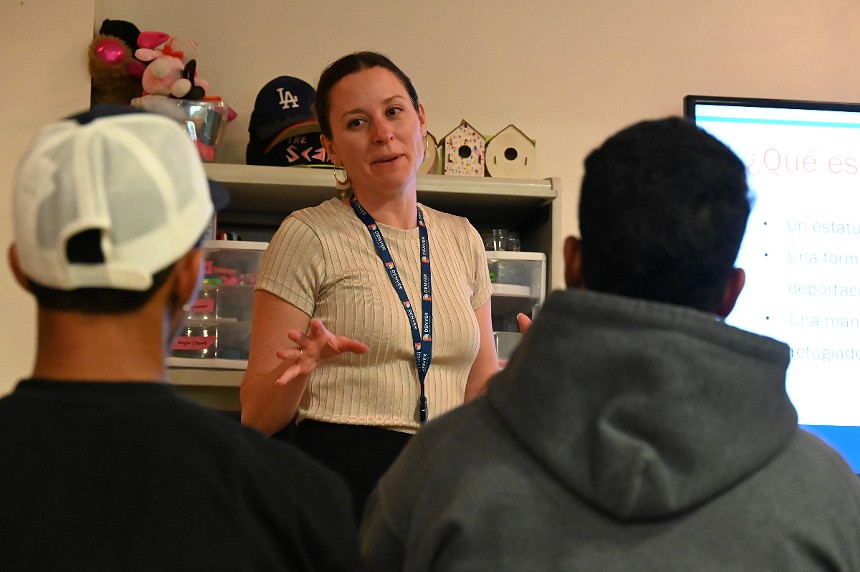

Sarah Plastino, the director of the Newcomer Program and career immigration attorney, has been welcoming migrants at the Mullen Home with a presentation in Spanish about asylum. It explains "what it means to apply for asylum, the requirements and the benefits of asylum," she tells Westword.

William Rodriguez and Marcy Mora sit with their daughter, Eliza, while participating in the Denver Asylum Seekers Program.

Bennito L. Kelty

Plastino wants "to ensure that they want to be part of the program" and what asylum entails first, she notes. Because once they start, there's no going back.

"Everybody in the newcomer group is in immigration proceedings. They have an open case with an immigration judge, so they have to put forward a defense or they'll be ordered deported," she says.

The first slide on the presentation reads "What is Asylum?" and has three bullet points below: a legal immigration status, how to avoid deportation, and how to convert to refugee status.

Seeking asylum requires a "credible fear," meaning there's a real possibility that they'll be persecuted or harmed if they return home, Plastino told a small group of migrants on Monday, May 13. The most common question she gets from migrants after finishing her explanation is if their reason for leaving Venezuela will hold up as a credible fear in court.

"The people that come up to me and ask, by and large, have quite strong cases," she says. "Most people qualify for asylum based on the reasons they left their country and why they're afraid to go back."

Applying for asylum requires filling out a packet of information in English, a few thousand dollars in attorney fees and a "legally cognizable asylum claim," Plastino says. Denver's program will take care of those costs, translation and assist with writing the asylum claim, all of which is covered by $6 million in the mayor's new migrant budget.

Participants also have to get an explanation of DASP from Papagayo, the Village Exchange Center and ViVe Wellness staff before they sign up to begin the program. The nonprofit staff members explain the program, its requirements — including no illegal activity and a commitment to filing asylum — and steps of the asylum process.

Plastino notes that the asylum application involves a difficult submission process that requires mailing applications to the right judge. Migrants won't get a public defender if they can't afford an attorney, either, she points out. They also have to keep track of documents along the way and send them to various agencies.

"It's just very logistically complicated; it's in the dark ages," she says. "It's very hard for someone to do if they don't understand the court system, they don't read or speak English, they can't pay an attorney. And you also have to do all this before your one-year anniversary in the U.S., or else you don't qualify."

William Rodriguez and Marcy Mora came to the United States a month and a half ago with their one-year-old daughter, leaving two other kids behind in Venezuela. They've been staying at the Quality Inn migrant shelter west of downtown Denver, which is run by the city, but visited the Mullen Home to learn more about application for asylum.

The couple fled Venezuela out of fear of "'political persecution and to find asylum from that bad quality of life that there is in Venezuela," Rodriguez says.

They came to Denver because a friend of Rodriguez's told them it was a good place to raise a family and "very beautiful," he says. Rodriguez, Mora and their daughter enrolled in the DASP program on May 13, and Rodriguez says it will offer "hope that I can be with my kids again, that I can bring them with the opportunity this provides.

I'm really satisfied they offer this support."

He's also impressed with "the affection they give to migrants" in Denver, he says. "In reality, there are some that come to cause trouble, and there are some of us that are here [that] want to help the city."

Rony Blanco and Yenire Cirilo came from Venezuela and arrived in the U.S. four months ago. They're living with rental assistance from Papagayo, and feel "grateful" and "comfortable," Blanco says. The two of them began DASP on May 13, and Blanco plans to work in construction when he's through.

"We left Venezuela because of threats, problems we had with the government," Blanco says. "We like Denver because it's calmer than other states."

Sarah Plastino, director of Denver's Newcomer Services Program, explains to migrants what asylum is.

Bennito L. Kelty

The city has yet to decide how long DASP will run. The $90 million migrant budget — which pays for DASP and other programs like WorkReady — is meant to get Denver through 2024. The city may have to reevaluate after six months, Ewing says, but it's "just focused on launching" DASP for the time being.

"We'll also see what the world will look like in six months. There's a big election coming;, there could be any number of changes," Ewing says. "This is a massive project to roll out. Even though it's based on best practices from other groups, there's nothing like it anywhere, so it may be an informed approach, but you're building it from scratch."