DHA has been nationally recognized for the plan, now under construction, as a model for sustainable and equitable development. DHA has also been recognized for its implementation, receiving the “Community Impact Award” from NAIOP Colorado in March.

I began working in the Sun Valley neighborhood in February 2020, and until April 2023, I worked for four organizations there, each driven by a moral and political commitment to Sun Valley’s low-income residents.

First, I worked as a consultant for the Sun Valley Kitchen + Community Center, a food pantry, community hub and low-cost, social enterprise restaurant that delivers job training and professional development opportunities to Sun Valley’s youth and adults.

Second, I worked as a project manager for the Westside Stadium Community Coalition, an advocacy group made up of residents and community leaders advocating for equitable development in and around the Sun Valley neighborhood.

Third, I worked for History Colorado, a museum and cultural institution, and helped lead a “Museum of Memory” project collecting oral histories and working to preserve the stories and memories of Sun Valley residents as the neighborhood underwent change.

Finally, I worked on the development team at Urban Ventures, LLC. My work at STEAM on the Platte was my introduction to the neighborhood, and I served as one of the liaisons between the Sun Valley community and our team.

On one of my first days in Sun Valley, Glenn Harper, the founder of the Sun Valley Kitchen + Community Center, took me on a driving tour of the neighborhood. We drove through the DHA-owned public housing property, the Sun Valley Homes, and I saw for myself their physically distressed state. Screen doors were broken; paint was chipping. The buildings were clearly aging and lacking maintenance.

Yet the human energy was abundant. Large families spilled out of their homes into adjoining yards. Children played together. Parents sat on the grass or hung laundry on lines. Everyone was talking or laughing.

Introducing me to everyone by name, Glenn handed out leftover meals from the food pantry and explained that the redevelopment would force most of these families to vacate their homes so they could be redeveloped and upgraded. Luckily, DHA had plans to complete demolition of the Sun Valley Homes in stages so that residents would be able to relocate within the neighborhood instead of being temporarily displaced into DHA properties in other areas of the city.

He and other Sun Valley community leaders were hopeful. DHA had spent the better part of a decade collecting input from residents and involving them in the planning process. The redevelopment would be disruptive, he said, but in the end, it would benefit everyone.

A “National Model for Redevelopment” Gone Wrong

The Denver Housing Authority received so much attention for its redevelopment plans because, unlike other recipients of CNI grants (and those from similar programs like HOPE VI), DHA had committed to “redevelopment without displacement.” Their planning process had included extensive community engagement, and residents were reassured that, though construction in the neighborhood would be disruptive, they would be able to remain in their community while it was completed.Unfortunately, just as DHA was getting ready to break ground, the coronavirus pandemic swept across the globe. Supply chains were disrupted and labor shortages arose. The pandemic also brought permitting delays and unforeseen infrastructure challenges. Cumulatively, these complications increased construction costs, sometimes $20 million over projections, and threw DHA’s construction timeline off track.

Sometime during the spring of 2020, Sun Valley residents were informed that DHA had rescinded its commitment to them, and they would not be able to stay in the neighborhood during the redevelopment. Shortly after, the majority of Sun Valley residents were relocated to other DHA properties so construction could begin.

After just a few months of working in the neighborhood, I watched as the diversity and connectedness that had given it life slowly dissipated. Before the redevelopment, residents were made up of mostly African and Asian immigrants or refugees. Over thirty languages were spoken, making it one of the most diverse neighborhoods in Denver.

One resident insisted that, though the neighborhood was “isolated,” it was also “insulated” from the outside world in a way that brought everyone closer together.

According to urban scholar Edward Goetz, the forced displacement and relocation of low-income residents resulting from public housing redevelopment is quite common. HUD-funded programs like the Choice Neighborhoods Initiative and HOPE VI were created to redevelop traditional public housing — which is often in physically, racially and economically segregated neighborhoods with little access to basic amenities like parks, public transit or grocery stores — into mixed-income, mixed-use neighborhoods.

The social goals of the programs are twofold: first, encourage mixing across socioeconomic classes through mixed-income housing and the integration of middle-class residents into high-poverty neighborhoods; second, bring basic services and amenities to previously isolated neighborhoods through mixed-use developments and investments in public infrastructure.

Yet the evidence that these programs — and the housing authorities that administer them — have the ability to deliver on these outcomes is questionable. Simply introducing middle-income people into high-poverty neighborhoods through market-rate housing development does not guarantee social mixing.

Further, displacing residents — many of whom are unable to come back due to new income restrictions on affordable-housing units and/or unforeseen bureaucratic hoops — means that the neighborhood’s new and improved amenities will not be enjoyed by the very people who need them most.

In Sun Valley’s case, all but seventy of the over 300 families living in the Sun Valley Homes were displaced. Three years later, in March 2023, 20 percent of Sun Valley’s original residents had returned. With a nationwide return rate for public housing redevelopments around 15-20 percent, it’s questionable how many more will be able to.

I Changed How I Think About Gentrification

In 2019, I wrote an article for the National Civic Review titled “We Need to Change How We Think About Gentrification.” In the article, I argued that holistically labeling development “good” or “bad” was too simplistic.Further, I argued that “gentrification” and “displacement” were not one and the same. Gentrification is simply when a neighborhood gets wealthier, I said, and displacement is not always the inevitable result of gentrification.

My intention was to quell some of the fear I saw in city leaders of causing gentrification by investing or developing in low-income communities. I believed, and still do, in the power of equitable development to be a tool for social, racial and economic justice.

However, my experiences in Sun Valley have changed me. Ruth Glass, the urban sociologist who originally coined the term "gentrification," defined it as having two qualities: displacement of low-income residents and change in neighborhood social character.

I saw both happen in Sun Valley. I saw low-income families who had lived there their entire lives uprooted from their neighborhoods, distanced from essential community services, and disconnected from their support networks and friends.

I also saw the neighborhood's character change. By the time I had completed all of my Sun Valley projects in April 2023, rowhomes had become apartment towers, middle-income people had moved in, and private, market-rate housing dominated the development landscape.

The tight-knit, intergenerational, interconnected and diverse community that had been there for decades was gone.

After working in Sun Valley, I now know that the negative outcomes associated with gentrification — displacement and neighborhood character change — are still very real risks for low-income communities. And publicly sanctioned gentrification — or the forced displacement of low-income communities by governmental institutions — is not a thing of the past.

We Can Do Better

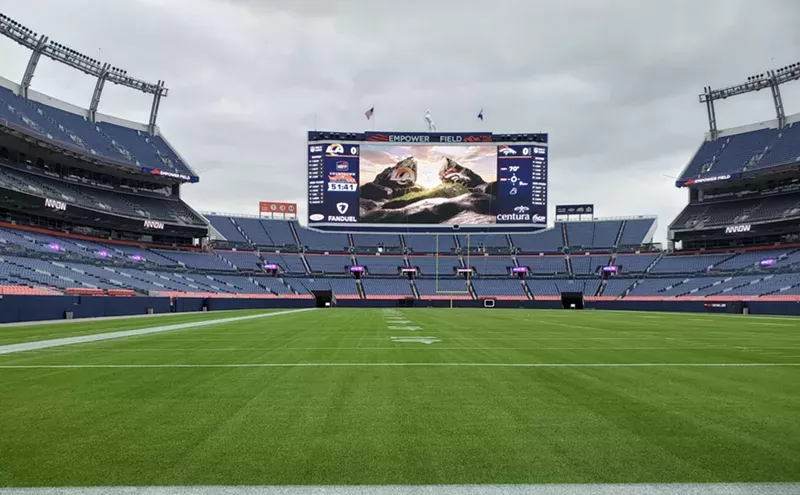

I wish I had come away from my experience in Sun Valley with an epiphany about how to do equitable development right. Instead, I left confused, angry and sad. I completed my Sun Valley projects in April 2023, and I haven’t returned to the neighborhood save a quick drive to the Broncos’ stadium. I don’t know how many more residents have returned since last year.In my final months in Sun Valley, community leaders were fighting to save the elementary school from closing due to low enrollment (with so many families displaced, few children were left in the neighborhood). They lost the fight, and one of the few remaining essential services in the neighborhood was gone.

Ten years from now, I wonder what types of amenities will have replaced it? With market-rate construction booming and Sun Valley’s proximity to downtown, the Broncos’ stadium and public transit, there are still plans on the horizon for a new “Stadium District” development there. A Community Benefits Agreement between the Sun Valley community and the project’s master developer has been promised, yet I now have less faith in such promises. Even if a CBA does become realized, will it be the original Sun Valley residents who benefit from it?

One thing I do know is that a reckoning is in order, with ourselves and with our governments, about our implicit beliefs about who is disposable — or whose lives can be negatively impacted by public policy — and who is not.

Every urban planning student knows the story of Jane Jacobs, the mid-twentieth-century activist who fought city planning behemoth Robert Moses and saved Greenwich Village from being razed for a highway. But how many of us learn about the fights that ended with loss — the umpteen examples of low-income communities destroyed for one public project or another, the communities displaced for highways, public parks, universities or simply “clearance” and “renewal?”

How aware are we that such projects are still happening, and that in them the well-being of low-income communities is considered an acceptable casualty of our urban ambitions?

This past March, when returning from a visit to Orange County, California, the pilot made an announcement: “We do something a little special here in Orange County out of respect for the nearby communities; if you hear the engines get quiet during takeoff, it’s nothing to worry about.” The hotel shuttle driver had warned me about this, too. “All the rich people in Newport got the airport to limit its hours,” he said, “and the planes are extra quiet when they take off.”

In sharp contrast, a couple of months later I attended a conference on urban forestry at Colorado State University, and a resident of one of Denver's low-income neighborhoods recounted his childhood growing up next to Denver's Interstate 70. "I used to lie in bed and pretend the sound of the cars was the sound of the ocean," he said. Multiple members of his family were diagnosed with asthma or other lung conditions as a result of the neighborhood's excessive air pollution.

We might consider, as a collective society, what mental hoops we need to jump through to accept significant requirements on an international airport to protect the ears of the wealthy, yet we deem the steps necessary to protect the basic well-being of low-income people impossible.

We might ask ourselves what policy changes or “special accommodations” are suddenly on the table when a community poses a real monetary or political threat. And what are we willing to do to the communities that don’t?

All with a hand in urban development would do well to remind ourselves of the humanity in each and every low-income community, particularly urban communities of color. For it is only our disconnection from them, our dehumanization of them, and our inability to empathize with them that make the harm we inflict on them possible.

Lindsay M. Miller is the founder of Beyond Growth Strategies, an equitable development consulting firm.

Westword.com frequently publishes commentaries on matters of interest to the community on weekends. Have one you'd like to submit? Send it to [email protected], where you can also comment on this piece.