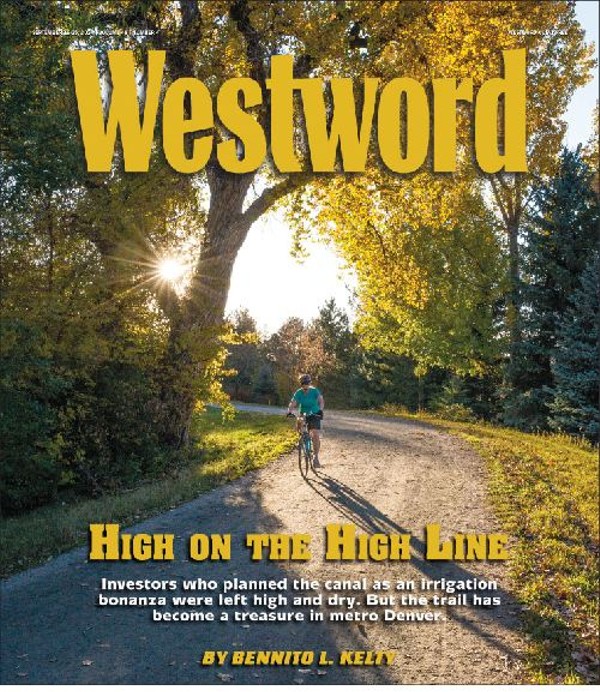

The High Line Canal may never have become the liquid asset it was intended to become, but today it's one of metro Denver's greatest amenities.

In 1880, James Duff saw the low valley in this part of the arid plains and envisioned building the biggest irrigation canal in the American West.

Duff was a businessman, a Scottish immigrant who'd organized a Confederate Texas cavalry during the Civil War, fled to Mexico when the Union won, then rebuilt his life in Denver. After opening the elegant Windsor Hotel downtown, he became vice president of the Colorado Mortgage and Investment Company, the most prolific canal builder in the state, according to National Park Service archives.

He began working alongside Englishman James Barclay, his fellow vice president at CM&I, engineer Edwin Nettleton, and engineer and entrepreneur (and future Colorado governor) Benjamin Harrison Eaton, who'd been trying to build a large canal project in Larimer County.

The group had it in mind to build a gravity-fed canal based on the high-line principle, which suggested moving water from the highest elevation point possible to lower levels through a ditch. Duff believed the best place to start this High Line Canal was Waterton Canyon, the final passage for the South Platte River from the Rocky Mountains to the yawning Great Plains.

Eaton, an Ohio native who came out to Colorado to strike it rich during the state's gold rush, liked the high-line principle because it would allow him to carry water farther. He promised Duff that they could build the longest canal west of the Mississippi, 71 miles, and irrigate 120,000 acres of land.

Construction crews working for Eaton began building the canal in the spring of 1880, with 160 teams of ditch diggers recruited through newspaper ads offering a dollar a day plus board. Using shovels and donkeys but no machinery, the diggers worked nonstop until November 30, 1883, completing the High Line at a cost of $650,000. It wasn't as large as the Erie Canal, the giant 180-mile waterway that awed Eaton in his youth, but it was the largest irrigation canal built in the West, and the most expensive.

To stay on the most elevated point, the canal meandered through the dry, arid grasslands of Douglas, Arapahoe, Denver and Adams counties. It ran alongside farm lands and ranches built on land sold by members of Duff's group, including railroad magnate Jay Gould, who spurred the project to attract settlers to land he owned east of Denver.

But the South Platte River proved unpredictable, and the water rights that Duff had secured were weak and too junior. In the first few years of the High Line's operation, Duff managed only 1,200 cubit feet of water per second (or 651,000 gallons of water a day), which would only be enough to irrigate 60,000 acres of land, half as much as Duff had hoped.

Worse yet, the canal had problems with seepage, water evaporation and carrying the water the full 71 miles. The diversion dam and sluice gates, which allowed additional water to pass, were sturdy, but the sand and gravel that traveled with the water blocked the gates and other parts of the headworks that surrounded the dam. Gophers also tended to burrow into the banks of the canal, weakening the walls.

As a result, the High Line Canal was only going to be able to irrigate 50,000 acres at best — but the reality turned out much worse. In its first few years of operation, it only managed to irrigate 20,000 acres of cultivated land, mostly in Douglas and Arapahoe counties. Water wouldn't even travel out of Arapahoe County except during heavy rainfall, and that was rare.

Farmers were angry that their crops along the High Line Canal were failing. In 1892, farmer David Richards successfully sued Duff's Northern Colorado Irrigation Company, a CM&I subsidiary created to manage the canal, for damages for crops he lost between 1884 and 1889. The lawsuit set the stage for other farmers to sue, and the company became entangled in constant costly litigation.

“The English Ditch was a blunder," read a 1902 Denver Times article, using one of the canal's nicknames to distinguish it from the Farmers' High Line Canal that began near Golden and the Rocky Ford High Line Canal that starts near Manzanola. "The ditch has been a losing investment to the owners. It cannot get enough water legally and there is reason to believe that it cannot succeed in stealing enough.”

A new group of investors, including some from CM&I, formed the Antero and Lost Park Reservoir Company with the goal of building a new water district west of Pikes Peak with storage dams that could deliver more water to the High Line Canal through another major waterway project. But then the company decided instead to just buy the High Line Canal for $600,000, believing its engineers could improve the water flow.

In 1913, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled that the City of Denver had the right to build or buy its own water plant, and the city responded by asking the Denver Public Utilities Commission to find a reliable long-term water source. After studying options near Clear Creek and the Blue River, among others, a consulting engineer from Los Angeles recommended in 1914 that Denver buy the High Line Canal.

Denver City Council refused to give the Public Utilities Commission additional funds for more studies of the High Line Canal, however, and the resulting feud led to city leaders putting a question on the May 1915 municipal ballot asking whether the commission should be dissolved. Voters rejected the idea.

By August 1915, the commission saw that city leaders weren't interested in putting a single penny into buying the High Line Canal, so it went ahead and bought the canal secretly for $1.1 million from the Antero and Lost Park Reservoir Company.

In 1920, after 165 days of trial, the Colorado Supreme Court decided that the commission had the power to buy the canal. The Antero and Lost Park Reservoir Company retained control of the canal until May 24, 1924; after that, the High Line Canal became property of Denver Water, an agency formed in 1918 that replaced the city's public utilities commission.

This wasn't the last time the city would find itself all wet where the High Line was concerned.

Today, the first marker of the High Line trail appears south of Chatfield State Park in Littleton, near the end of Waterton Canyon.

Bennito L. Kelty

The High Line Canal rarely flowed the full 71 miles. The City of Aurora, which changed its name from Fletcher in 1928, has rarely seen any South Platte River water, notes Harriet Crittenden LaMair, who eventually became involved in stewarding the canal as head of the High Line Canal Conservancy.

When water did come down the canal, residents used it recreationally. They tied ropes to branches and made swings to fly into the canal. They swam in it or floated down it. Kids looked for salamanders and toads left in the muddy ditch of the canal after rainy days, LaMair recalls.

In the 1960s, Denver Water began to consider turning the service road that ran alongside the canal into an official trail.

Like the canal itself, the accompanying service road crosses Jefferson, Douglas, Arapahoe, Denver and Adams counties. The road was originally for "ditch drivers" to travel between the 165 headgates and direct water at different parts of the canal. But now the thought was to use it for recreation.

In March 1970, the South Suburban Parks and Recreation District, which had formed in 1959 to create parks for multiple cities south of the City and County of Denver, came to an agreement with Denver Water to use eighteen miles of the service road as a trail dedicated to hiking and horseback riding, according to Denver Water. Later that same year, Denver Water agreed to let Aurora use twelve miles of the service road for recreation.

Four years later, Denver Water began planning to develop thirteen miles of the service road into a trail. It then finalized an agreement with the State of Colorado to do the same for the remaining portions of the road.

Today that road is a trail whose composition changes from county to county. The first few miles, south of Chatfield State Park, are bare and rough, uncrowded by the trees that stick close to the canal; at some points, the trail is just a bumpy dirt road with small, muddy pools of water in tire tracks and balls of horse manure nearby.

As the trail approaches newer housing developments in Douglas County, it's paved smooth with concrete like a sidewalk and travels past freshly erected park canopies and gazebos where you can rest in the shade. In Arapahoe County, portions that are still dirt give way to gravel for miles before the trail winds farther into Cherry Hills Village, where it's paved with blacktop.

In Cherry Hills Village, the trees and the houses close in on the trail and shade it for miles, pushing flies and mosquitoes that hang around the damp bed of the canal closer to the trail. The ranches turn to mansions, and suddenly the High Line is in south Denver, winding past churches and under busy roads. It begins to hit more traffic lights and crosswalks where cars have to yield.

This is the only trail in the metropolitan area that crosses Interstates 25, 225 and 70, and it does so quietly, with mural- and graffiti-painted tunnels taking it through underpasses hidden from motorists. In east Denver, the trail hits a rise, offering a look at how far it's traveled from the foothills of the Front Range and how far it has to go through backyards with short fences behind drab apartment complexes.

The High Line Canal tangles with the Cherry Creek Trail for a few miles near the Denver and Aurora border, around Havana Street, before it abandons Hampden Avenue and C-470 to head due north. In northern Aurora, before it reaches Green Valley Ranch, the land looks as high and dry as it did in Douglas County, but the trail is freshly paved and feels smooth under bike tires and hard under feet. An overpass opened in June that crosses over Peña Boulevard.

The trail ends in Green Valley Ranch, a few miles south of Denver International Airport. This high point on the plains offers a panoramic view of development projects currently encroaching on the area.

The High Line crosses Highway 285 in Cherry Hills Village with a stone-walled underpass.

Bennito L. Kelty

So in 2014, fans formed the High Line Canal Conservancy, a nonprofit dedicated to stewarding the trail alongside its government partners. Harriet LaMair, who raised her kids near the High Line, has been the CEO since the start of the organization.

The group started small, with cleanup days and community projects, but was soon thinking big: Today it has $67 million in federal and state funding, and is raising another $33 million, with a big benefit slated for September 20 in Aurora.

From 2025 to 2029, the conservancy will use that $100 million to improve the trail's connectivity by closing gaps around Plum Creek in Littleton, at Wellshire Golf Course in Denver and near I-70 in Aurora, adding new trails, bridges and underpasses and smoothing surfaces all along the way. It's also putting up educational signage about the wildlife and plants along the trail, and about the history of the High Line.

And there's still plenty of history to be made.

While the conservancy has been taking an increasingly important role in the High Line Canal, Denver Water began to hand off ownership of the canal this spring, keeping only a 45-mile stretch that goes through Green Valley Ranch and assigning the rest to Arapahoe County.

Denver could have taken on a portion, but declined...just as it had over a century ago.

The city had budgeting concerns about maintenance, while Arapahoe County was ready and had plans and funding in place. Denver Water worked collaboratively with the Denver Department of Parks & Recreation, the Denver City Attorney, Arapahoe County and the High Line Conservancy to move forward with the conveyance of the land to Arapahoe County, but with an understanding that when Denver is ready, the city can take the Denver parcels back.

In the meantime, Arapahoe County is converting the ditch into a stormwater system, while continuing to encourage recreational use of the trail. According to Greenwood Village, it's "one of the most popular and treasured areas of the city."

As a trail, the High Line Canal found new life. It's one of the longest contiguous urban trails in the country, and is used by about a million people a year as a walking, biking and equestrian trail. It's used for irrigation "very infrequently," says LaMair. "It's better known as a recreational trail."

Author David Skari, who wrote Meandering Through Time, a history of the High Line Canal, says that even though it flopped as an irrigation project, it inspired bigger schemes that went on to help Colorado residents claim water and survive in the arid climate of Denver.

"It was very instrumental," Skari says. "The building of the High Line Canal was a radical departure from anything that had been built in its time, and it gave people the idea, 'Hey, look what can be done.' It was surpassed only by more grandiose projects, and the story of Colorado is water reclamation."

Part of the trail's value is that it ties the metro area together while still displaying the character of the different communities, LaMair says. It passes by stables with horses and goats and parks with children and dogs. Even if it failed in its initial mission, its creators should be proud of what they did.

"What would those people think today? Wouldn't they be so pleased?" LaMair muses. "Sometimes what happens is people have an idea and it changes. But I don't think anyone, not even a landscape architect, could have designed something like the High Line Canal."