September 23 concluded a three-day public hearing that inspired 700 written comments and 117 in-person testimonies from residents over that time.

The bike park was proposed near Shadow Mountain Road, which originally sparked concern from Conifer residents who view the road as unsafe. At the hearing, however, some residents expressed their support for the idea, arguing it would bring tourism dollars to Conifer.

Although the chances are slim, Jefferson County Commissioners could still reverse the planning board's decision. The proposal is on the docket for an October 1 hearing, but the commissioners have already planned to continue until November 12 to allow enough time for research and preparation.

County planning staff recommended against the permit, finding that the use of a private, commercial bike park didn’t fit within the applicable land-use rules, which stipulate that any recreational projects must be public. At the end of the hearing, commissioners agreed with the staff's recommendation to deny the application despite thinking that a bike park is a good idea.

“I hope to visit your bike park one day,” said Commissioner David Duncan. “I just am not convinced that it is compatible with this location. I think you have a fantastic idea. I hope you succeed in doing it, but this piece of property for this use is just not compatible.”

Commissioner Drew Bolin was persuaded that the land use was appropriate, but he believed that another condition was unmet: mitigating the impact on health, safety and welfare of residents and landowners nearby. Bolin echoed resident concerns about more cars climbing Shadow Mountain Drive and the potential impact on emergency medical services in the area.

“If it wasn't a two-lane with a school bus, I would feel a lot more comfortable,” he said. “I've been an extreme mountain-bike rider, and I have one rotator cuff surgery to prove it. I'm a huge fan. What you're doing is very exciting, but those concerns I just struggle with.”

The bike park idea came from Denver residents Phil Bouchard and Jason Evans, who moved to Colorado from New Hampshire. The childhood friends said they spent lots of time at a mountain-bike park in New Hampshire with an electric lift during their childhood, and hope to bring that concept to Conifer.

“Four years ago, we noticed a series of problems with mountain biking in Colorado,” Evans said at the hearing. “Just a few of those include significant pressure on trail systems today, a lack of dedicated biking infrastructure, significant user conflict, the overuse leading to trail degradation, and many more.”

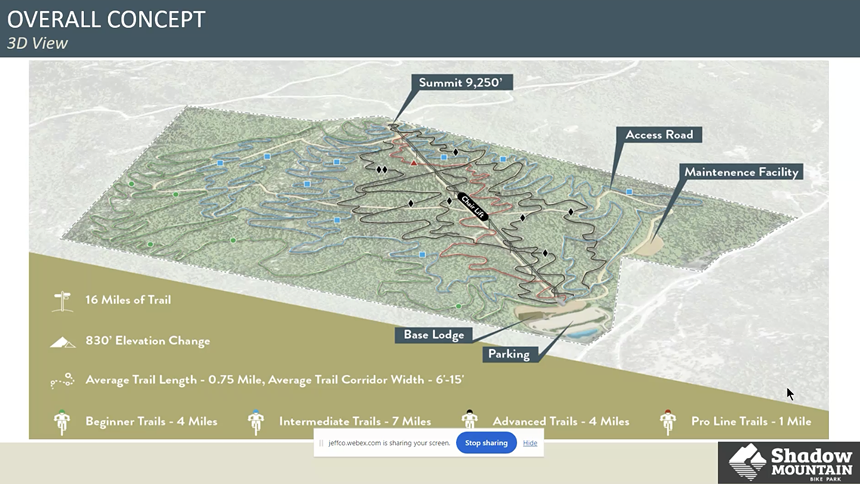

Their vision for Shadow Mountain Bike Park: sixteen miles of trails for skills ranging from beginners to professionals, with resources like bathrooms and flat tire repairs but keeping facilities generally uncomplicated. The chair lift would be brand-new, all-electric and only emit as much noise as a washing machine, according to the developers. A lodge and parking lot would be added, as well.

The land Shadow Mountain would sit on is owned by the Colorado State Land Board, which manages trust assets on behalf of public schools in Colorado, with earnings going toward projects to improve schools throughout the state.

The land board granted Evans and Bouchard a planning permit to develop a proposal, but the decision on how the land can be used is entirely up to Jefferson County. According to county zoning rules, the bike park would count as Class 3 recreation while the land is only zoned for Class 2 recreation, which is why a special-use permit was required to move forward.

The park would have a chair lift for easy mountain access.

Screenshot from Developer Presentation in Public Hearing

Why Residents Oppose the Bike Park

Residents who are against the bike park said they have nearly 6,500 signatures on their petition against the development, including those of 3,421 people who live within a few miles of the proposed location. Many of the written comments submitted to the commissioners came from members of Stop the Bike Park, a group formed to oppose the project.“Sorry for the time it took you all to read all of those letters, but hopefully it helped you to understand that this isn't just NIMBY neighbors complaining,” resident Jennifer Hohn said during the September 23 hearing. “There are serious issues around the proposal’s impacts on our residential neighborhood that just cannot be mitigated.”

Chief among those issues is the potential impact on wildlife.

“I have seen bears, foxes, coyotes and hawks,” said Randall Bruenlin, who said he used to drive along Shadow Mountain Drive every day on his commute to work. “I can't imagine the devastation to our wildlife if this project would move forward. I believe the foothills of Jefferson County are a special and unique place. The peaceful serenity and the beauty of the meadows and mountainsides and the wildlife are the reasons we all live here.”

Audrey Boag, who identified herself as a consulting naturalist who does plant and bird surveys in Jefferson County, said the stretch of land where the bike park would be contains some of the most biodiverse ecosystems in the county. According to Boag, the bike park could displace 44 species of nesting birds and three imperiled plant species.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife recommended a seasonal closure of the bike park from January through June to protect wildlife in the area, particularly elk who live and breed there in the winter and birth calves into the summer. The bike park agreed to open only from April through November, but the commissioners were hesitant about the timeline given its difference from CPW’s recommendation.

The developers indicated they were open to trying to negotiate a better closure timeline for wildlife, but their proposed timeline was based on feasibility of the business.

Safety concerns were the other top worry for residents in opposition, including how the bike park would impact the potential for, and response to, wildfires. Bike park developers predicted a little under 1,000 one-way car trips would be added to Shadow Mountain Drive on peak weekend days; the park would have a vehicle capacity of about 300 spaces, 60 percent of which would turn over throughout the day.

“I have personally seen several accidents along this road during the summer months when this bike park will be in operation,” said resident Ken Rillings. “I've also been actually turned away by the police when the road was completely closed due to an accident.”

Chris Crowley, who worked as a volunteer EMT in Jefferson County, said he has responded to “horrific” crashes and believes that adding more cars to the road would only cause more. Other residents pointed out that even through May, there are snowdrifts that can be difficult to navigate.

Examples of what a trail at the park might look like.

Screenshot from Developer Presentation in Public Hearing

“I did some cursory analysis of this and found that the majority of these crashes…would have occurred during the closure period of the proposed park during times of inclement weather,” Monke said. “We do not expect any effects on health, safety and welfare of the residents or landowners in the surrounding area.”

The commission generally did not agree.

“I see there's going to be traffic congestion, and the high intensity of use just boggles my imagination,” said Commissioner Wendy Spencer. “This is primarily a residential area.”

Why Residents Support the Bike Park

Some Conifer residents did support the project, pointing out that the State Land Board’s goal is to generate revenue, so something will have to go on the plot eventually — and building a housing development or mining area would be much worse, they argued.“There are some people in Conifer who are against any change whatsoever, but change is inevitable,” said resident Eli Olhausen. “Conifer is going to change, and, really, what's important is to help it change in the right way. I firmly believe this bike park is the right kind of change.”

Many residents were excited by the prospect of another recreation choice, with several parents testifying they would be happy for their children to go ride bikes safely there. Others said they believe Evans and Bouchard would do right by the land.

“I'm confident that the State Land Board, Jefferson County and the developers of the bike park are working together to execute this in the best way possible,” said resident Tammy Deranleau.

Diana Caruso Jenkins, a legal consultant with the developers, pointed out that although a bike park isn’t specifically listed as a community use in Jefferson County, it would bring many of the same benefits as a rec center or golf course, both of which qualify.

Melanie Swearengin, former executive director of the Conifer Area Chamber of Commerce, added that the bike park would likely help stimulate the local economy, as visitors would stick around to eat meals or shop before and after their biking excursions. The park is designed to have minimal on-site dining and shopping options for that reason, the developers added.

Bouchard and Evans project an annual revenue of $3 million to $5 million in the first few years, but predicted that number to hit $12 million once the facility is fully built out.

“I know there's a huge group of community members that support this project,” Swearengin said. “Many are hesitant to speak out due to the charged atmosphere that this topic has brought.”

Those supportive residents, and the developers, will have one last chance to save the project when it goes before the county commissioners for approval.