According to Mohamedbhai, the Denver Police Department has formally confirmed that its reversal of a policy allowing officers to shoot at moving or fleeing vehicles, divulged in June 2015 shortly after then-Denver District Attorney Mitch Morrissey decided against criminally charging the cops who'd gunned down Hernandez, was a direct result of the January 26, 2015, shooting — something the DPD had previously been reluctant to acknowledge. In addition, he reveals that the city has instituted a policy against releasing the criminal history of police-shooting victims immediately after incidents as a way of implying that they got what they deserved.

"A volatile situation can be made worse by a PR campaign smearing the victim," Mohamedbhai points out. "They're not going to do that anymore."

Mohamedbhai adds that the City of Denver has treated the Hernandez family with compassion and respect throughout the negotiation process — and he hopes this behavior will become the rule going forward rather than the exception.

The settlement follows the DPD's determination in January that the two officers who fired shots into Hernandez's vehicle — Gabriel Jordan and Daniel Greene — would not be subject to discipline for their actions. The year-plus delay in reaching this conclusion was based on several complicating factors. Included among them: The Office of the Independent Monitor, one of several agencies that looked into the case, felt that while Jordan's actions didn't violate departmental policy, the evidence in regard to Greene was less conclusive.

Here's the Denver DA's Office account of the events that led to Hernandez's death, along with photos from the scene included with the original document, referred to as a decision letter.

On Sunday, January 25, Jose Carmen Guzman-Bonilla informed authorities that his Honda Civic had been stolen.

That night, Hernandez and four friends, identified only by where they sat in the car (for instance, "FSP" for "front-seat passenger"), drove around to several locations in the Honda — and the lack of consistency in terms of the survivors' memory of where they went was used to attack their credibility as witnesses.

As an example, one of the teens said Hernandez started the car using a screwdriver rather than a key, after which the group "went and picked up weed from Thornton" and visited a McDonald's, where they narrowly escaped notice from a cop — details none of the other occupants mentioned, according to the report.

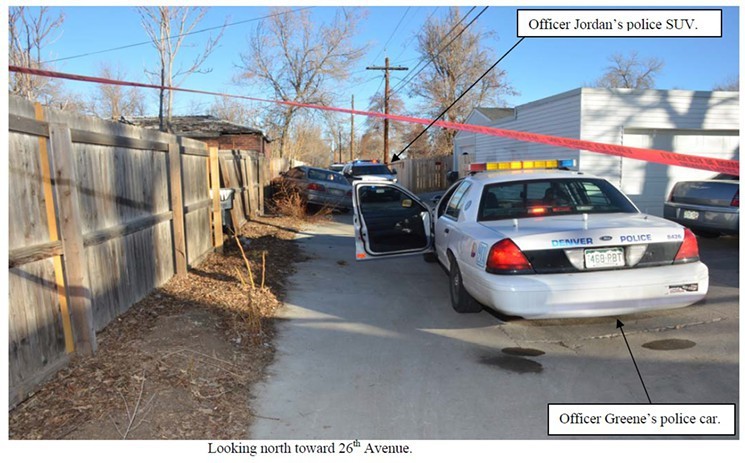

Around 2 a.m. or 3 a.m. on the 26th, Hernandez parked the car in an alley behind a residence at 2511 Newport Street, and everyone inside fell asleep.

Around 6:30 a.m., a neighbor called police. Initial reports suggested that he'd done so because the people in the car had been playing music loudly, but there was no mention of that in the letter. The document says the man merely reported a "suspicious vehicle" with its windows fogged up.

Officers Jordan and Greene arrived just shy of 7 a.m., parked in the alley and determined that the car had been stolen. Shortly thereafter, one of the teens spotted the police cars and awakened the others. "They're starting to get hinked up and moving around a lot," Jordan radioed to supervisors.

Two minutes later, shots were fired.

Jordan's account of what happened states that he turned on the emergency lights of his vehicle, drove closer to the front of the Honda, which was facing him, and yelled, "Police! Get out of the vehicle! Police! Get out of the vehicle!"

At that point, Jordan said, he saw a door on the driver's side of the Honda open, and "what looked like a Hispanic male looked back and then ducked his head back in and shut the door."

Next, Jordan told investigators, the Honda backed up slowly toward Greene's police car and either made contact with its bumper or stopped just before touching it.

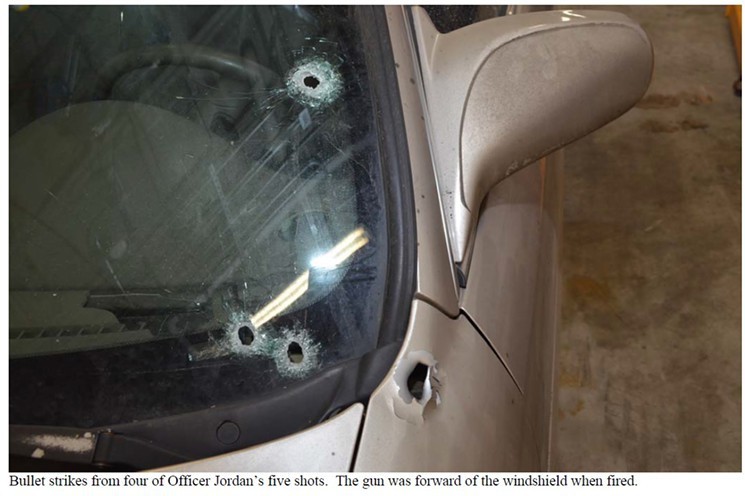

The close-up look at the bullet-riddled car in which Jessie Hernandez died.

Courtesy of the Denver District Attorney's Office

Instead, Jordan maintained, the Honda reversed again in the direction of a wooden fence, which it hit along with a trash container.

In response, Jordan moved around his vehicle toward the Honda, running along its side, at which point "the car engine revs up and it comes directly at me...driving right at me at a high rate of speed."

Jordan said the car came within "inches" of him, prompting him to open fire with the gun in his right hand as he pushed away on the fender of the car with his left hand. A quote:

"I waited till I had to hit the car away and I'm thinking now I'm going to go — I'm going to get squished and — and killed, and right then is when I fired. And...I'd be surprised if my gun wasn't touching the driver's side — the window."

Greene's separate statement agreed with Jordan's in every significant detail, as did that of a neighbor, Crystal Engler. An excerpt from her statement reads:

"Instead, the car ended up like kind of accelerating, and like — like moving toward the police, like right toward the police and — and I did see an officer get hit, and it was kind of like he bounced off of it — you know what I mean? It was like — like, 'Oh my goodness!'"

The witnesses inside the car had different recollections of events. The FSP said "she never saw an officer get hit by the Honda and she did not see an officer in the path of the car," the report states.

The other passengers concurred with this basic contention, but the report stresses variations in their statements and the fact that the windows were foggy, perhaps obstructing their views.

From there, the report delves into aspects of the crime-scene investigation, complete with details about the eight bullet holes that punctured the Honda and their trajectories, as well as Hernandez's autopsy results. She had two gunshot wounds to her torso and one to her pelvis and right thigh — "four wound paths that were caused by three bullets," the letter allows.

The analysis determines that "of the eyewitness accounts, the physical evidence only supports the accounts given by the two officers and by Ms. Engler.

"The physical evidence is compelling evidence that Officer Jordan was where he described being when he fired his shots," the account continues. "The fact that the teenage witnesses did not see Officer Jordan there during the undoubtedly frantic and traumatic moments of the shooting is understandable under the circumstances. The teenagers had been consuming marijuana and alcohol, had just awakened from their sleep in a car, and their vision was obscured by the foggy windows."

Based on this information, Morrissey foresaw that criminally prosecuting the officers would lead to "a jury finding that the officers’ use of deadly force was justified" — so he didn't press any charges against them.

Immediately after Morrissey's finding, the Denver Police Department released the aforementioned new rules against shooting into moving vehicles — a tactic that had previously been criticized by Independent Monitor Nicholas Mitchell. The edict reads in part: "Firearms shall not be discharged at a moving or fleeing vehicle unless deadly force is being used against the police officer or another person present by means other than a moving vehicle."

After the rule's unveiling, attorney Mohamedbhai said that had this policy been in place the previous January, Hernandez would still be alive — and today, he stresses that sadness over her fate still lingers.

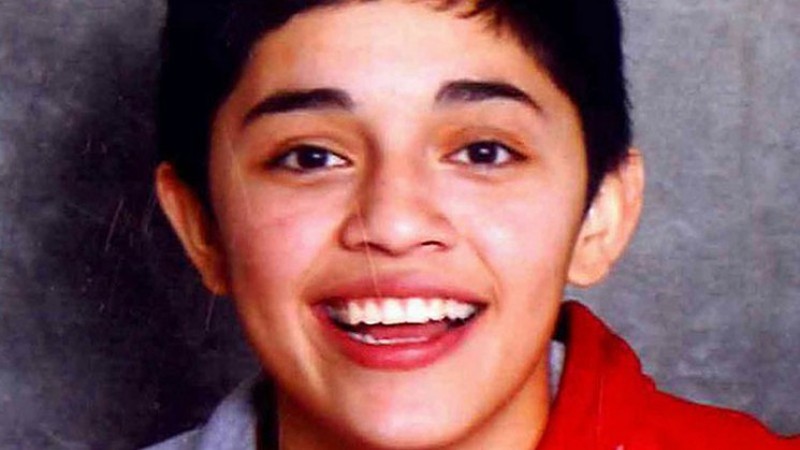

"There were about a thousand people at her funeral, and that was because of who she was," Mohamedbhai allows. "She was charismatic, and her whole life was about happiness and joy and love. She was a good student and she had a profound effect on her classmates and the people around her."

These qualities only made the DPD's character assassination of Hernandez after the shooting that much more painful, he adds. "Denver reached out to Adams County and released Jessie's pending juvenile charges. And that caused a major reaction. It was like, 'Why do you guys do that?'"

More recently, the city has done better, Mohamedbhai feels.

"About three months ago, the mayor [Michael Hancock] met with the family in an hour long conversation," he says. "It was mostly between Jessie's mom, Laura, and the mayor, but a lot of other people were there: the whole Denver City Council, [Denver Police] Chief [Robert] White, the manager of safety, human rights people. There weren't many dry eyes, and Laura was so compelling."

Many observers expected that the family would file a lawsuit — but, Mohamedbhai goes on, "their big thing was, they didn't want violence, they didn't want the community to be torn apart, they didn't want the relationships between law enforcement and communities of color to deteriorate further."

This attitude was accompanied by Mayor Hancock's willingness to take part in settlement talks prior to the appearance of a suit. "There was some tough communication with the lawyers," Mohamedbhai concedes. "But the city showed us humanity and compassion. They didn't want to put the family through a lawsuit, and they knew the facts of this case are horrible on both sides. So we tried to find a resolution that would honor everyone."

In his view, the agreement achieves this goal. "I don't believe these officers woke up that morning headhunting to kill a girl, and I'm sure it's something they're going to regret for the rest of their lives," he says. "On the flip side, I'm sure Jessie would have wished that she'd made some different choices — although certainly nothing she did should have been a fatal choice. And everyone recognized how hard going to court would be on everyone."

In Mohamedbhai's previous dealings with the city over such matters, "I've never had a well-thought-out settlement like this, pre-lawsuit. I think it showed a commitment on everyone's part to spare our community from what would have been nightmarish litigation. But unfortunately, nothing can bring Jessie back."