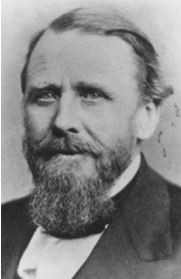

The announcement from the Colorado Department of Transportation, the U.S. Forest Service and Denver Parks and Recreation didn't mention another potential roadblock: the mountain's namesake, John Evans. As Colorado's second territorial governor, Evans commissioned Colonel John Chivington to establish the Third Colorado Calvary, a troupe of volunteers known as the "Bloodless Third" until close to 700 men attacked a peaceful chiefs' camp on the banks of Sand Creek on November 29, 1864, killing an estimated 200 Cheyenne and Arapaho, most of them women, children and elderly men.

Along with Chivington, a Methodist minister when he wasn't leading a massacre, earlier that year Evans had founded the Colorado Seminary, which later evolved into the University of Denver. The Evans name is still all over DU, and in recent years the school has been grappling with how to handle that decidedly bloody legacy.

On the eve of the 150th anniversary of the Sand Creek Massacre, a DU investigation determined that if Evans didn't give the outright order for the massacre, he created the climate that made it possible.

In addition to a mountain, Evans is remembered with a street that runs through Denver, as well as a town on the plains. Chivington, meanwhile, was memorialized with a village bearing his name not far from the site of the Sand Creek Massacre 170 miles southeast of Denver; appropriately, Chivington is now a ghost town.

While the Sand Creek Massacre Commemoration Commission was planning a proper way to observe the 150th anniversary of that horrific event, one group launched a petition drive to wipe Chivington's name from the map. But tribal descendants on the commission disagreed with that move. They wanted people to have reminders of what had happened, put in historical context. They wanted people to never forget...

But they do.

During protests against the murder of George Floyd that spilled out into indictments of law enforcement and racism in general, protesters have gathered by the Civil War Monument just outside the Colorado Capitol. Erected by the Colorado Pioneers' Association in 1909, the statue of a cavalryman, rifle by his side, includes a list of Coloradans who died in the war, as well as "battles and engagements" fought by Colorado troops.

It lists Sand Creek as a battle, not a massacre, even though that atrocity was the focus of three congressional investigations during the Civil War, one of which called it a "gross and wonton outrage," another determining that it was indeed a "massacre." Evans was soon forced out of office; in 1895, he got a mountain as a consolation prize.

In 1998, as Congress was considering the creation of the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site, Colorado lawmakers finally read the fine print on that Civil War statue and proposed removing Sand Creek from the list of battles. But descendants of the Arapaho and Cheyenne killed there objected.

"It's my own opinion that it was placed there for a reason," the late Laird Cometsevah, a Cheyenne leader, said at the time. "It's part of Colorado's history. You can't deny the fact that [Sand Creek] was a massacre. It seems to me that a man ought to be able to stand up and accept what he did, to live with it, and try to use the statue as a symbol for teaching young people that we don't want that to happen anymore. Colorado ought to be big enough to leave it there and try to improve its statehood. It ought to be left alone."

The descendants were backed by historians. If the Sand Creek name was erased, suggested then-state historian David Halaas, so would be the name of Joseph Aldrich, a private from Fort Lyon who refused to participate in the slaughter and died at Sand Creek, possibly by friendly fire. And Captain Silas Soule, who also refused to join in the attack, and later took aim at the atrocities during congressional testimony. In April 1865, Soule was assassinated on the streets of Denver by Chivington supporters.

"There are various things wrong with tempering history for today's audience," said Halaas, who'd helped identify the Sand Creek Massacre site and continued to work with tribal descendants until he passed away last August. "Once you start monkeying with one incident, where do you stop?"

Here's where: A move to erect an actual monument to the victims of the Sand Creek Massacre on the grounds of the Colorado Capitol grounds is now stalled. So are two proposals to change the name of Mount Evans; the U.S. Board of Geographic Names, which handles such requests, relies on input from the governor's office in the states where the disputed sites are located, and Colorado is currently stuck on that name game, too, as requests begin piling up across cultures, across the country.

But in 1999, the Colorado Legislature did take action. Rather than erasing past sins, it acknowledged them, placing a placard by the Civil War Monument that explains what really happened at Sand Creek, and how a "tragedy" had been mischaracterized as a "battle." And that November, at the end of the first Sand Creek Massacre Healing Run that has since become an annual event, a young runner climbed the Civil War Monument and counted coup — touching the enemy and living to tell the tale.

The true story.

Here are the words on the the Sand Creek Massacre Interpretive Plaque at the Colorado Capitol:

The controversy surrounding this Civil War Monument has become a symbol of Coloradans’ struggle to understand and take responsibility for our past. On November 29, 1864, Colorado’s First and Third Cavalry, commanded by Colonel John Chivington, attacked Chief Black Kettle’s peaceful camp of Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians on the banks of Sand Creek, about 180 miles southeast of here. In the surprise attack, soldiers killed more than 150 of the village’s 500 inhabitants. Most of the victims were elderly men, women, and children.

Though some civilians and military personnel immediately denounced the attack as a massacre, others claimed the village was a legitimate target. This Civil War Monument, paid for by funds from the Pioneers’ Association and the State, was erected on July 24, 1909, to honor all Colorado soldiers who had fought in battles of the Civil War in Colorado and elsewhere. By designating Sand Creek a battle, the monument’s designers mischaracterized the actual events. Protests led by some Sand Creek descendants and others throughout the twentieth century have since led to the widespread recognition of the tragedy as the Sand Creek Massacre.

This plaque was authorized by Senate Joint Resolution 99-017.