In June 2018, Larimer Square, Denver’s most historic and beloved block, landed on the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s list of the eleven most endangered places in the country. In its listing, the National Trust cited a development proposal that called for partial demolition of several historic buildings, the potential construction of two towers, and the weakening of a groundbreaking Denver ordinance that had long protected the famous block.

Within nine months, Larimer Square owner Jeff Hermanson and development partner Urban Villages announced that they’d spiked their initial proposal that had so outraged the community. In addition to the towers, they’d wanted to build affordable housing that Denver badly needs; a hotel, restaurant and bar; and rooftop gardens — a great idea...on paper. But residents, preservationists and civic leaders alike worried about the impact of the project on the character of the block, and their loud concerns sent the partners back to the drawing board.

A year later, the coronavirus pandemic has put even more roadblocks in their potential plans for the 1400 block of Larimer Street.

In the Beginning

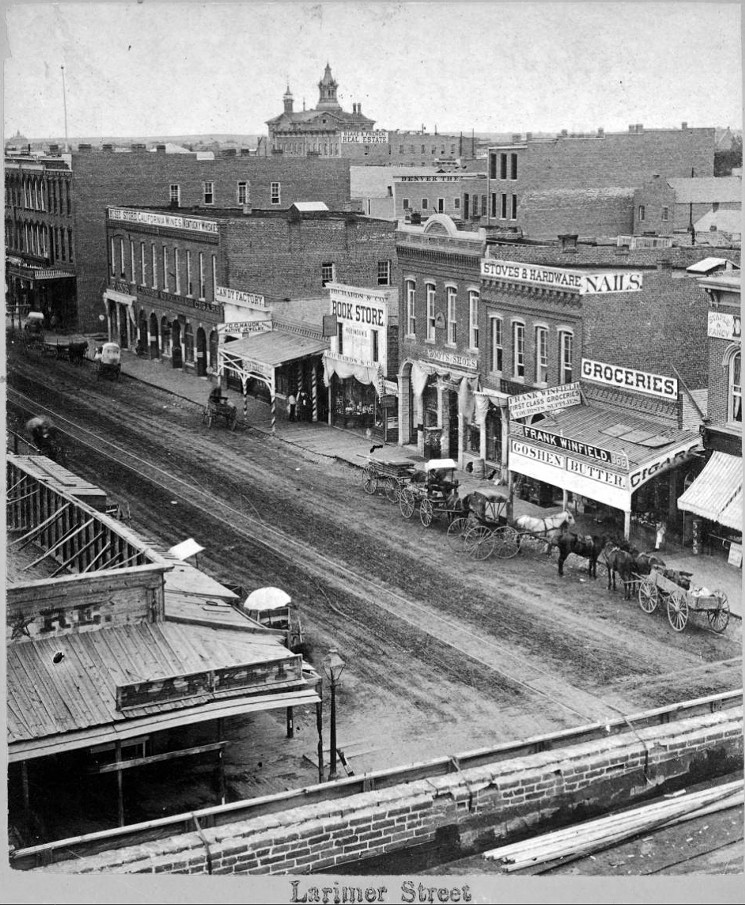

From the day Dana Crawford arrived in Denver in 1954, she began searching for a place where people could gather for socializing, dining and shopping. While the Salina, Kansas, native had been living in Boston, she’d fallen in love with the city’s vast inventory of historic buildings, and she hoped to find something similar, if smaller, in Denver. While raising four boys with her husband, John, she explored the city — and in 1963 she discovered the perfect spot, on Larimer Street between 14th and 15th streets, in the heart of what was then Denver’s skid row.“This is where Denver started,” says Crawford. “There was an enormous amount of inventory here that reminded me of the buildings in Boston. I became obsessed and possessed with the idea of saving it.”

Some of the buildings still standing on the block dated back to the 1870s, making it the oldest block of commercial buildings in Denver. Crawford began buying up the properties, with the goal of transforming the block into a shopping and entertainment district. Denver City Council designated Larimer Square the city’s first historic district in 1971, just a year after Historic Denver was founded in an effort to save the Molly Brown House Museum, onetime home of Margaret Brown, who’d proved “unsinkable” when the Titanic went down in 1912.

Larimer Square’s history stretches back even further. It was home to Denver’s first bank soon after the city was founded in 1858, as well as its first bookstore, dry goods store and photographer. The original City Hall, demolished in the 1940s, had stood on the grassy corner of 14th and Larimer by Cherry Creek.

While most of those early buildings were gone by the time Crawford came on the scene, there were plenty of other Victorian structures still standing. Crawford filled them with national tenants like Williams-Sonoma, Ann Taylor, Talbots and Laura Ashley, as well as some local enterprises. One of them, Gusterman’s Silversmiths, is still doing business in Larimer Square.

In 1986, Crawford sold Larimer Square to the Hahn Company, which owned shopping malls across the country and had just opened the Tabor Center in downtown Denver. But Hahn proved ill-equipped to operate a historic destination and in 1993 sold it to Jeff Hermanson, whose Larimer Associates already owned several restaurants on the block. But as downtown developed, Larimer Square fell behind.

In 1999, Larimer Associates hired David Levine, director of vision and vibe at Dallas-based Urban Partners, as a consultant. His mission was to resurrect the ailing historic district, whose tenants were fleeing to lower downtown and Cherry Creek North. Levine’s advice to Hermanson was to populate the block with chef-owned and -operated restaurants and independent boutiques.

When Levine and Joe Vostrejs, who was then responsible for the block’s operations, started thinking about repositioning Larimer Square, they realized that if they drew a line from the Pepsi Center to Coors Field and another from Mile High Stadium to the Colorado Convention Center, they would cross at Larimer Square.

“That was one of the ways that we were able to entice locals and new-to-the-market tenants,” Levine recalls. “The venues are critical.”

Between 1999 and 2004, Hermanson closed Cadillac Ranch, Josephina’s and Tommy Tsunami’s in favor of shifting to chef-driven restaurants. He began partnering with chefs and operators to establish successful restaurants on the block and in other real estate he owned throughout the city. Larimer Associates would provide the human resources, accounting and marketing services, enabling chefs and operators to focus on what they do best.

Levine persuaded nationally renowned restaurateur Richard Sandoval, who’d initially been looking at the West Village development in Dallas, to take a chance on Larimer Square. Sandoval opened Tamayo at the corner of 14th and Larimer streets in 2001, and it quickly became wildly successful, paving the way for other restaurants to take a closer look at the block."People started thinking of it again as a dining destination rather than just a tourist destination."

tweet this

Still, it took a while for Larimer Square’s reputation — which still had the tinge of a tourist trap — to catch up with reality. In 2003, restaurant consultant John Imbergamo asked a local attorney if she wanted to invest in Rioja, a new restaurant that chef Jen Jasinski planned to open with her business partner, Beth Gruitch, in Larimer Square. “She loved Jen and Beth and loved the food,” Imbergamo recalls, but her response was, “Sure. Where is it?”

That lack of local recognition didn’t deter Rioja’s owners, however, and Larimer Square became a pioneer in clustering chef-driven restaurants in a defined area of Denver, years before chefs started branching out to other parts of town.

“At one point, there were seventeen food-service licenses on Larimer Square, including Starbucks and the Market — more than any other block that I know of outside of New York — on one block between 14th and 15th,” Imbergamo says. “It turned Larimer Square around. With the influx of new talent, new concepts and up-and-coming chefs like Jen and Troy [TAG owner Troy Guard], people started thinking of it again as a dining destination rather than just a tourist destination.”

Abandoning Redevelopment

But while Larimer Square had been successfully transformed into a go-to destination not just for tourists, but for residents of Denver, other competing developments were soon popping up all around in the city’s red-hot real estate market. Four years ago, Hermanson partnered with Urban Villages, a Denver-based developer, on a variety of ground-up projects across Denver, as well as Larimer Square, which Urban Villages currently manages.

Early in 2018, they floated the idea of positioning Larimer Square for the future with an ambitious project that would not only raise $60 million for a backlog of much-needed preservation work, but would also set up the block for additional development. The proposal called for demolishing the rear of four historic buildings and the construction of two new buildings set back from the street but taller than the block’s 64-foot height restriction.

Larimer Square’s historic-district status allows for a variety of building uses, including affordable housing, offices, hospitality, artist spaces, retail and restaurants — even innovations that no one has thought of yet. But while changes to historically designated buildings and districts are permitted, they must first be reviewed by Denver’s Landmark Preservation Commission to ensure that they are compatible with the design, scale, architectural features and building size that make the district distinctive. That wasn’t going to be an easy sell, given Larimer Square’s status.

Because Larimer Square was Denver’s first protected historic district, changing its legal protections and design guidelines would open up a can of worms for the rest of the city’s 53 historic districts, including the entire Lower Downtown Historic District (it starts where Larimer Square ends at Market Street) and the nearly 350 individually designated landmarks in Denver, says Annie Levinsky, executive director of Historic Denver Inc.

And even before the partners could go to the city for permission to break out of zoning restrictions, they had to deal with opposition from people who believed the block should be left as is.

Six months of meetings with stakeholders led to no resolution, and in March 2019, Larimer Associates and Urban Villages announced that they would no longer seek the demolition of any historic structures. Meanwhile, that February, Urban Villages had opened an outreach center in Larimer Square to collect public input. “We’ve learned a lot since we presented our first draft of a plan to restore Larimer Square,” says Jon Buerge, chief development officer of Urban Villages. “During that time, our team has been listening to our various audiences."We've always believed building new buildings can help solve those renovation needs."

tweet this

As part of our promise to be completely transparent in our approach, we opened a visitor center...and invited the Denver community to tell us what they think. We received over 35,000 individual responses — from town hall meetings, social media and handwritten notes. We reviewed every one of them, and they’re helping to inform our next steps.”

Steps that got sidetracked by the coronavirus pandemic but have not disappeared altogether.

“All of the renovation needs haven’t gone away just because of COVID,” says Buerge. “We’ve always believed building new buildings can help solve those renovation needs. That will continue to be part of the solution; we’re just not sure of timing yet.”

Businesses operating in Larimer Square pay a mandatory 1 percent fee on all sales (single items costing more than $1,000 are exempt). The fee funds external restoration, preservation or beautification improvements that benefit Larimer Square and generates a couple hundred thousand dollars each year. But that wasn’t nearly enough to cover the $60 million worth of work needed to preserve the facades of the buildings lining both sides of the block, and their interiors also required upgraded structural work and mechanical systems.

Larimer Square’s owners say that whatever their next proposal looks like, it will include new construction and renovation of some of the current buildings. But in the meantime, the team is keeping the focus on how to help tenants along the block survive the pandemic.

And once again, restaurants are key.

At Your Service

On June 19, Larimer Street between 14th and 15th streets was closed to vehicular traffic in order to accommodate more outdoor dining.That was a development that many hope becomes permanent.

Robert Zimmerman owns Element, a home-furnishings store that’s been a Larimer Square tenant since 2008.

He says the block was like a ghost town from mid-March until the city granted permission for the street closure, and he hopes it stays closed. He was so enthusiastic about the closure that he even proposed building a massive glass dome that would be open in nice weather and closed during inclement weather, but the Larimer Square ownership group said that such a structure would be prohibitively expensive.

“Restaurants definitely affect the business,” Zimmerman explains. “Larimer is restaurant-driven, and we retailers definitely count on that. I think it would be a great thing for Larimer to be closed to traffic. We don’t have the results yet for how it’s affecting business, but it’s nice to see people meandering around. It makes it much more relaxed.”

Those customers also help pay for continued upkeep. “As a renter, that affects our cost,” says Zimmerman. “We have to pay for a lot of the maintenance, too. It’s expensive. Buildings were not really meant to be this old.”

Not everyone agrees that the street should be closed permanently.

“If there is no automobile traffic, it seems like there are no people,” says Crawford.

Vostrejs, who left Larimer Associates a few years ago to start City Street Investors, a real estate investment and development firm, worries that the historic block could lose its authenticity if the street remains closed beyond the pandemic.“One of the things I’ve always cherished about Larimer Square is that it was Denver’s original main street,” he says. “Something happens when you close the street; it becomes maybe a little too precious.

I’m worried about losing some element of its grittiness. I would not like to see Larimer Square completely populated with Gucci, Fendi and Rolex stores. I like the mix of cool, little locally owned boutiques.”

Even so, Urban Villages would support a permanent closure.

“This COVID situation has brought people together and the support of street closures,” says Buerge. “The LoDo District and Historic Denver are helping us to come up with creative ways to do pick-up windows in storefronts for to-go food. The city is being creative about liquor-license expansions.”

And restaurants need to be creative these days, particularly downtown. While there are still tourists who visit Larimer Square, business travel is down, and locals who used to attend events at the Pepsi Center and the Denver Center for the Performing Arts aren’t reserving tables at the block’s popular restaurants.

“I look for places that are adjacent or on the way to drivers — events or venues that create demand for restaurants,” Imbergamo says of factors he looks for when selecting locations for his clients. “If you have $200 tickets to Hamilton and it’s snowing, you’re not going to sit on your couch at home and say the heck with it.

You’re going to get off your ass and still do your dinner reservation and go to Hamilton, whereas if you just had a reservation, you cancel. Pepsi Center and DCPA are really integral to the success of restaurants on Larimer Square.”

Hamilton was slated to open last week at the Denver Center for the Performing Arts. But the pandemic put a stop to that run.

While restaurants seem to be enjoying success with their expanded outdoor seating, their owners are nervous about what will happen when summer fades and colder temperatures return to the metro area.

Jasinski, whose company owns Bistro Vendôme in Larimer Square in addition to Rioja, as well as restaurants Ultreia and Stoic & Genuine at Denver Union Station, thinks that a permanent closure of the street and adding infrastructure such as tents and heaters to accommodate winter dining would be a godsend.

“I can’t figure out winter,” Jasinski admits. “Nothing in my lease works with having fifty people inside the restaurant at one time. We need 150 people in it at one time. Fifty people is me going out of business.”

Absent more events bringing people to the area at night, what will help restaurants in Larimer Square the most is people returning to work downtown, she says. Neighborhood restaurants like Señor Bear and Bar Dough, spots that her husband, Max MacKissock, is involved with in LoHi, are faring better than their downtown counterparts, she notes.

Already, businesses that had been a part of the block for decades have closed because of the pandemic. Euclid Hall, whose lease was almost up, closed for good at the close of service on March 16, before Governor Jared Polis’s stay-at-home order closed all restaurants to on-premises dining the next day. In April, the Market announced that it would not reopen, after 42 years of business in Larimer Square. Also gone is Roxanne Thurman’s Cry Baby Ranch, a longtime Western-style store that was a favorite with residents and tourists alike."Something happens when you close the street — it becomes maybe a little too precious."

tweet this

And even before the pandemic, as Urban Villages and Larimer Associates worked on their plans, leases were not renewed. Longtime women’s clothing store Eve closed in February because of that.

But Hermanson isn’t daunted by losing so many businesses in such a short time. He says there is strong interest in those empty spaces, including from a concept similar to that of the Market.

“COVID was a purging moment,” Hermanson says. “Yes, it breaks my heart to say goodbye to Roxanne and to Mark at the Market and to close Euclid Hall, which was one of my businesses. But at the same time, it’s exciting because we’re dealing with new operators who want those spaces. This gives us the opportunity to re-tenant with more timely and relevant concepts.

“We’re the best real estate in the city. As people leave, more want to come. We’ve done a great job of activating and curating. We’re going to get to do it faster now.”

So far, the new Larimer Square lineup includes Bao Brew House in the former Euclid Hall space; Garage Sale, a pop-up in the 15th Street corner spot that Tom’s Diner vacated long before the pandemic; Farmer’s Market/Bazaar, a pop-up in the former Market space; Hidden Gems, an ice cream pop-up in what had been Timbuk2; Ghost Coffee Saloon, a coffee pop-up at the former Eve address; Buckley House of Flowers, a pop-up in the former Aillea space; and Fat Baby, an outdoor beer garden and burger pop-up in the alley between Larimer and Market streets, where LoDo officially begins.

The team is still working on pop-up concepts for the former Cry Baby Ranch and Frinje boutique spaces.

Forward Into the Past

Even Historic Denver president Levinsky, who led the charge when proposed changes at Larimer Square were revealed two years ago, is optimistic about its post-pandemic future. If the spaces can be filled, there are preservation tools such as federal and state rehabilitation tax credits that can help the block’s caretakers preserve the historic buildings, which will continue to draw people to the neighborhood.“The first places people are going to want to experience are those places with meaning, those places they have positive memories of,” she says. “Larimer Square can survive through this and thrive. The tools are ready and waiting.”

Some of those tools have attracted developers to the site of the original city hall, now owned by Buzz Geller of Paradise Land Co. Until recently, the sliver of land had been under contract to San Antonio-based Kairoi Residential, which had proposed developing a 36-story apartment tower there, but that project was scuttled; Geller says he’s in discussions with a different developer.

A recent charrette examined three parcels along Speer Boulevard by Geller’s property to determine how they can be developed to complement the historic block, Levinsky notes.

Participants discussed how to improve the pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure to improve the connection across Speer; the potential for a future connector route along Larimer across Speer; and providing active uses along Speer. The Auraria campus also has said it would like to see a bridge built over Speer at Larimer.

Still, there are challenges that come with developing those parcels. Access to the site will be difficult, and curb cuts to accommodate disabled people are unlikely on Speer. And developing the north side of Larimer will be tricky because of the view plane, which limits building heights.

The City and County of Denver, which owns the parcels, wants potential buyers to consider affordable housing if they plan to develop them.

Vostrejs thinks that delaying redevelopment of the block until there is a clearer picture of what the future holds is a wise decision. While he expects restaurants to continue to play a pivotal role in Larimer Square’s destiny, “you can’t just have food and beverage,” he says. “We used to joke that you can’t window-shop another restaurant after you’ve just had dinner.”

But even as Larimer Square businesses focus on surviving the current COVID-19 crisis, its owners are looking to the future.

“If I was to grab a silver lining from this horrific episode, COVID has been an accelerator in terms of us transforming the block,” Hermanson concludes. “It gives us the opportunity to do what we’ve always done, which is to reinvent the block.”