The Castle Rock Libertarian, who is known for her electric pink hair and Statue of Liberty crown, had found herself in the middle of a schism over the direction the party should take.

She discovered the Libertarian Party in 2014, a year after she moved to Castle Rock from Florida to be with a man she’d met online and would soon marry. After she used the word “libertarian” in a debate on Facebook, she realized that she didn’t actually know what the word meant. She looked it up, and ended up on the Libertarian Party website. As she read the platform, it clicked instantly that this was what she’d been looking for in a political party; she considered herself a RINO because she was a registered Republican but had never really participated in politics.

“I literally changed my mind within a space of fifteen minutes,” Harlos recalls. “All I did was read the platform and say, ‘Holy crap, this makes sense.’ And I switched my voter registration on the spot.”

Harlos has always been liberal on social issues, but has never approved of what she sees as oppressive government intervention. There was space for both of those positions in the Libertarian Party.

She soon threw herself into the party. Her husband, Wayne Harlos, became a Libertarian the year after she did; before that, he’d considered himself part of the Tea Party wing of the Republican Party. Together they formed the Libertarian Party of Douglas County in 2016, the year she was first elected as Region 1 representative to the Libertarian National Committee. She served as the secretary of the Libertarian Party of Colorado; Wayne is currently the state party chair.

And then she decided to go for a national office. A paralegal and registered parliamentarian, Harlos is an expert on parliamentary procedure and Robert’s Rules of Order; she thought those qualifications made her a perfect fit to serve as national secretary. She was elected in 2018, then ran again in 2020. At the time, the upstart Mises Caucus was advocating that the party leave behind its recent, pragmatist past and advocate for an end to government interference in economics, localization and single-issue coalitions to achieve policy goals.

Harlos was sympathetic to that position. But then she discovered that a certain faction of the party considered her very much out of order.

The Libertarian Party got its start in Westminster, Colorado, in 1971. That’s when David Nolan, his wife and three of their friends were watching the news and heard that Richard Nixon planned to intervene in the economy in ways that they saw as overstepping.

They decided to start their own political party, gathering others who felt the same way and holding a press conference announcing the formation of the Libertarian Party in January 1972. That year, the first Libertarian National Convention was held in Denver.

The party took off fast. By 1980, it was on the presidential ballot in all fifty states. Today it’s the third biggest political party in the United States, with 2.4 million voters registered nationally as of October 2021. Colorado had 42,000 registered Libertarians as of 2020.

The party stands for individualism and opposes any form of government intervention; as a result, it shares beliefs with both the Democratic and Republican parties. For example, Libertarians have long supported gay marriage, decreasing the prison population and ending foreign intervention in wars, all positions that align closely with liberal ideals. But the party also supports limited federal government, abolishing taxation, and unregulated economic activity, items that align closely with conservative ideals.

To gain traction, at times the party has leaned toward a more pragmatic approach to national politics, emphasizing parts of the platform that are more agreeable to the masses — particularly Republican masses — such as less taxation and smaller government rather than the ideological purity of no taxes at all.

Mary-Kate Lizotte, a professor of political science in the Department of Social Sciences at Augusta University in Georgia, co-authored a 2021 paper titled “Understanding the appeal of libertarianism: Gender and race differences in the endorsement of libertarian principles”; she says she suspects that the pragmatist wing of the Libertarian Party leans Republican because it prioritizes individualism and lack of government interference over its other values.

“Democrats also often largely endorse that idea of a meritocracy and self-reliance as well; they just happen to prioritize egalitarianism over that individualism, and I think with Libertarians, it’s just the opposite,” Lizotte says. “They’re more in line with the Republican Party, which also tends to prioritize individualism.”

The party member who gained the most recognition from that pragmatist approach was presidential nominee Gary Johnson, who won 4 percent of the popular vote in the 2016 election. On the other side of the spectrum was Ron Paul, the party’s 1988 nominee, who advocated for ideological purity rather than chasing mass appeal.

In the book Beyond Donkeys and Elephants: Minor Political Parties in Contemporary American Politics, Christopher Devine, an associate professor of political science at the University of Dayton, says that the question of whether the Libertarian Party should be “purely a vehicle for libertarian, lowercase L, ideology or if it should be a kind of libertarian-flavored party that can actually win elections” has haunted it for years.

Devine’s research found that, in general, those who voted Libertarian weren’t as radical as the party’s platform. But looking back on it now, he says that his 2020 analysis almost feels like an obituary because of the ways that the party has changed since then.

“Maybe this is just a brief detour and then they come back to where they were,” Devine adds, “but to the extent that this is a lasting change, it seems like a major shift in the party and a real break from the first fifty years.”

At the heart of the change is the Mises Caucus. Named after the Mises Institute, a Libertarian think tank in Alabama that follows the Austrian economics principles of its namesake, Ludwig von Mises, the Libertarian Mises Caucus was founded by Michael Heise in 2017. Its political action committee has raised $356,000 in 2022 alone, according to the nonprofit OpenSecrets.

Some caucus members consider themselves part of a radical arm, swooping in to save a party that doesn’t know what it is anymore. But while Libertarian Party membership seems to be leaning more intensely toward ideological purity, Devine points out that Ron Paul remains the father of the movement.

“What it reminds us, really, is that the Libertarian Party has not been one thing throughout fifty-plus years,” Devine says. “There’s always been some fluctuation between the relative strength of different movements within the party. I’m not saying this is just the same thing all over again; I think it is a shift, but to anyone who thinks that this is just an alien force taking over the party, I would say there are some deeper roots.”

The pandemic and resulting lockdowns and mask mandates may have helped shift the party toward a more radical viewpoint. Such policies go against the libertarian notion of individual choice and hands-off government, and explain why Angela McArdle, the new national party chair, decided to run in 2020.

The Libertarian Party had failed to take a stand on lockdowns, she says, missing a chance to let people know about the option of this third party.

“What I would like to do at the national level if we ever get locked down again — and hopefully that does not happen — is to say that we oppose it and that we believe that your ability to go outside, engage in commerce, and interact with your friends and family is one of your foundational liberties,” McArdle explains.

Harlos was also concerned when the national party failed to come out strong against lockdowns.

She calls Johnson’s style of libertarianism “thick libertarianism” and Paul’s “thin libertarianism.” Thin Libertarians, she says, believe that an individual’s personal opinions on social issues are irrelevant to their libertarianism as long as they don’t try to implement a law based on them. Thick Libertarians, on the other hand, believe in what thin Libertarians believe — but also demand that people be on a certain side of social issues.

Harlos saw masks as one of those issues. Although she’s on the more liberal side of many social issues — she believes in gay marriage, abortion rights and the legalization of sex work — she doesn’t think that they have a place in the Libertarian platform.

New Hampshire is a Libertarian hotbed, thanks to the Free State Project, founded in 2001, which recruited over 20,000 people to move to the state to start a liberty-minded community. The Mises Caucus became prominent in the state party.

It was too prominent for some, including then-New Hampshire Libertarian Party chair Jilletta Jarvis and then-Libertarian National Committee chair Joseph Bishop-Henchman. After Jeremy Kauffman, part of the New Hampshire party’s communications committee, took control of the party’s Twitter account and began sharing provocative statements — including one about legalizing child labor and another about repealing the Civil Rights Act — Jarvis attempted to break away from the existing state party and form a new one. Bishop-Henchman supported her, but much of the national party leadership, including Harlos, did not, and Bishop-Henchman eventually resigned in June 2021 over the issue.

Harlos stood up for the existing New Hampshire party, and exposed Bishop-Henchman’s coordination with Jarvis on attempts to form a new party. But members of the national party leadership — who believed that Bishop-Henchman had done the right thing, and that the Mises Caucus was infiltrating the party to its detriment — still held a majority at that time. They voted to remove Harlos from her position.

After that, similar movements to wrestle Mises Caucus power from local chapters in Delaware and Massachusetts emerged. Believing that those attempts were emboldened by her removal, Harlos tried to help the local caucuses, offering free services as a registered parliamentarian. And she joined the Mises Caucus herself.

“A lot of the Mises people, they’re younger people,” Harlos says. “They’re guys, usually, in their twenties; they don’t have a ton of money. Then older people, with more experience and more money, start coming against them. What are they going to do if somebody doesn’t step up to volunteer to help them? They’re pretty much helpless.”

She appreciates their focus on local Libertarian candidates and ballot measures, as well as creating new, county-level affiliates of the Libertarian Party. In Colorado, the Mises Caucus supported the 2019 Decriminalize Denver initiative that aimed to decriminalize psychedelic mushrooms.

Other single-issue campaigns supported by the Mises Caucus include creating coalitions for gun rights, legalizing gold and silver as legal tender, and pushing for further federal legislation of hemp.

Although Harlos felt secure in her choice to stand up for liberty, her removal from national office came at a difficult time. She’d just resigned her job as a paralegal, and it was tough to find a new one, because every potential employer would find the Wikipedia page that noted she’d been removed from her position within the party.

“People play these petty political games and don’t realize it follows people for the rest of their life when you do things like that,” she says.

Even after her ousting, Harlos stayed active in the party, documenting Libertarian history from records kept in a storage locker near her Castle Rock home. And she continued contributing to LPedia, the party’s collaborative website, cataloguing its history and happenings.

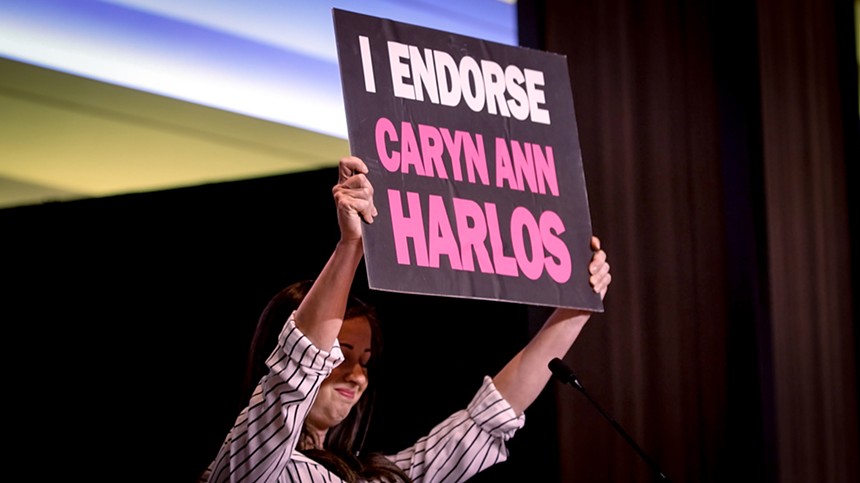

History turned around quickly. The Mises Caucus nearly swept the party elections this year. When Harlos went to the national convention, she was given back her position as secretary, and the party amended the official record to void her removal, noting that she hadn’t been given due process.

According to Harlos, only two of the newly elected national committee delegates aren’t members of the Mises Caucus or endorsed by it.

With the Mises Caucus firmly in power, the party now plans to move forward with a new vision, leaving behind “wokeness.”

But first, the people leading the Libertarian Party are going to have to deal with charges of bigotry.

For a time, Harlos says, the party had focused too much on forcing everyone to conform to the same set of social views rather than on opposing the coercive power of the state. “Some of the people who had more of the progressive views started…calling everyone who disagreed with them a Nazi and a bigot, which seems to be the stock-in-trade of today’s political discourse,” she notes. “The problem is, you say it enough times, you start to believe it, and when you think you’re fighting, like, literal Nazis, you will do almost anything.”

As a result, the Mises Caucus now advocates for leaving social issues out of the party platform and focusing purely on libertarian ideology. Harlos praises the party for being the first in America to “de-woke.”

“It signals, kind of, a return to fundamentals and not what I call ‘hiding the ball,’” Harlos says. “The ultimate position of the Libertarian Party — it’s shocking to a lot of people, because we haven’t said it for years — when we say we want the state out of things, we literally mean that.”

Under that view, the only roles for the state involve courts, police and a limited military. That means no public schools, no social welfare programs, no Americans With Disabilities Act and no declaring drugs illegal, among a slew of other positions.

“The reality is there are always going to be people who reject us in the mainstream,” McArdle says. “That should never give us a reason to compromise our principles. It should never be something that influences the fundamental decisions that we make regarding how we message liberty.”

According to Lizotte, third parties in the past have aligned themselves with a major party politically, as the Libertarian Party has done with the Republican Party. But moving away from that could be a logical next step, since that Republican Party alignment doesn’t seem to be winning the Libertarian Party many victories.

“If, at this point, they feel like that’s not getting them the end results that they’re looking for and that they’re just sort of being taken advantage of by the Republican Party and taken for granted, then I think it makes a lot of sense that they would sort of re-evaluate what they should be moving forward,” Lizotte says.

In her research, Lizotte found that people who support libertarian principles tend to deride the Democratic Party. But McArdle doesn’t buy Lizotte’s theory. She thinks the Libertarian Party has done too much lately to placate liberals rather than conservatives.

“We want to distinguish ourselves, obviously, from the other two parties, but not to be so nasty and combative to people who are social conservatives,” she says. “The party, historically, at least in the last twenty years, has done a lot to reach out to people on the left, but they have really kind of ignored, and maybe even ridiculed, people on the right. So what we’re trying to do is to outreach to people on both sides of the political spectrum without compromising our principles.”“We want to distinguish ourselves, obviously, from the other two parties."

tweet this

During the 2021 Pride Month, she points out, the national party sent an email about “pansexuality.” While the Libertarian Party has always defended gay marriage, McArdle says that pansexuality is a left-leaning buzzword that wasn’t needed to send the message that the party supports LGBTQ+ rights.

A political party’s platform can’t require its members to be a good person, Harlos says: “That’s nothing to do with a party. There are assholes in every party.”

To that end, at the 2022 convention in Reno, the party changed its platform. The line that used to condemn bigotry as irrational and repugnant was replaced with this: “We reject the idea that a natural right can ever impose an obligation upon others to fulfill that ‘right.’ We uphold and defend the rights of every person, regardless of their race, ethnicity, or any other aspect of their identity. … Members of private organizations retain their rights to set whatever standards of association they deem appropriate, and individuals are free to respond with ostracism, boycotts, and other free market solutions.”

“It basically says the same thing, but with less ambiguity — but for some reason, people lost their frickin’ minds,” Harlos says. “‘We condemn bigotry as irrational and repugnant’ — that’s not a political statement; that’s a virtue signal. What policy does that translate into in libertarianism? Nothing, but to say we defend the rights of all people? Now, that actually says something.”

The statement now indicates action rather than feelings, she points out. It doesn’t insist that anyone in the party has an obligation to condemn bigotry, or take action to defend someone else’s rights.

“I don’t think that equity keeps out bigotry,” McArdle says. “In order to make things quote-unquote equitable, you usually have to cut someone else down and remove them from their status. Oftentimes, that means you’re removing or cutting down someone who has worked very hard and achieved a position on their own merits.”

Although McArdle says the Mises Caucus actually has a more diverse makeup than the party at large, Devine says it tends to avoid specifically addressing its stance on bigotry. “They would not identify, I think, as supporting bigotry or prejudice of any kind, but they also don’t want to talk about it much,” Devine says, noting that the line condemning bigotry has been in and out of the party platform over the years.

“Mises Caucus folks will say, well, there’s no shift going on here. We’re just taking away some of the performative ‘wokeism,’ as they describe it, of the party in recent years, getting back to basics,” Devine continues. “A lot of other people say, ‘Come on, we can read between the lines.’ Not talking about certain things and then trying to provoke people on other points, this is a cultural shift, and one that has bigotry at its root.”

But Harlos points to herself as an example of how the Mises Caucus isn’t bigoted, much less leaning into Nazi-like ideas.

“Last I checked, Nazis didn’t like pink-haired white women who purposely chose not to reproduce and have lots of little white children,” she says. “Everyone’s realized that the cancel mob is great until it comes for you — and it always comes for you.”

Harlos believes that “wokeness” has caused people to always search for a reason that they’re a victim, taking attention away from those who are actually oppressed.“Everyone’s realized that the cancel mob is great until it comes for you — and it always comes for you.”

tweet this

The Libertarian Party simply doesn’t see a role for the government in preventing oppression, she notes. That’s why a popular saying in the party is this: “Some of the most terrifying words in the world are ‘I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.’”

If the government does need to step in, McArdle notes, it should be on a local rather than a federal level. Usually, though, it should be up to the individual and the community to fight back.

“We believe that individuals have the right to bear arms, that you can fight back against someone, and we don’t believe in Utopia,” she says. “We understand the fallible nature of human beings, and I believe that it’s reasonable to call upon friends and family and people around you for help.”

Now that the Libertarian Party has “de-woked” itself in order to focus on pure libertarianism instead of reaching out to disaffected Democrats and Republicans, Harlos thinks that its membership will increase.

“If you had a hamburger joint, maybe before trying to convince people who like hot dogs better that hamburgers are great, you reach for the people who already like hamburgers,” she suggests.

However, Devine questions how the Mises Caucus will measure success if not by winning more voters in national elections. “Who did Gary Johnson really inspire to become a lasting, committed, ideologically pure member of the party?” Devine asks. “According to the Mises Caucus? Not many. And there’s probably some truth to that, maybe some exaggeration. So for the Mises Caucus, how do they know that they’ve done a better job than anyone else?”

Devine suspects they will focus on local numbers in states and counties, as well as how many libertarian-minded ballot measures pass across the country. He thinks the question of how strong and lasting a shift this is for the Libertarian Party might not be answered until 2024, when the party nominates a candidate for president.

Will it be a Mises Caucus rabble-rouser like comedian Dave Smith, who headlined the 2022 convention of the Libertarian Party of Colorado? Or will it be someone like former Republican congressman Justin Amash, who might be a bridge between the party’s pragmatist past and radical future?

Either way, Harlos is excited. In the embodiment of the local focus touted by the Mises Caucus, she’s running for Castle Rock Town Council this November. The race is nonpartisan, but Harlos is making it clear that she wants to push the town closer to libertarian principles, with less government involvement in people’s lives.

“With actual, simple, clear, not-obfuscating-the-issue-of-what-we-believe messaging, I think that we could make a huge impact — and for third parties, an impact isn’t always winning elections,” Harlos says. “I don’t care if I’m in a room talking to five people or 500 people. You never know: The one person you’re talking to could be the person that’s going to change the world. Every person you talk to is important. It’s not only about numbers.”