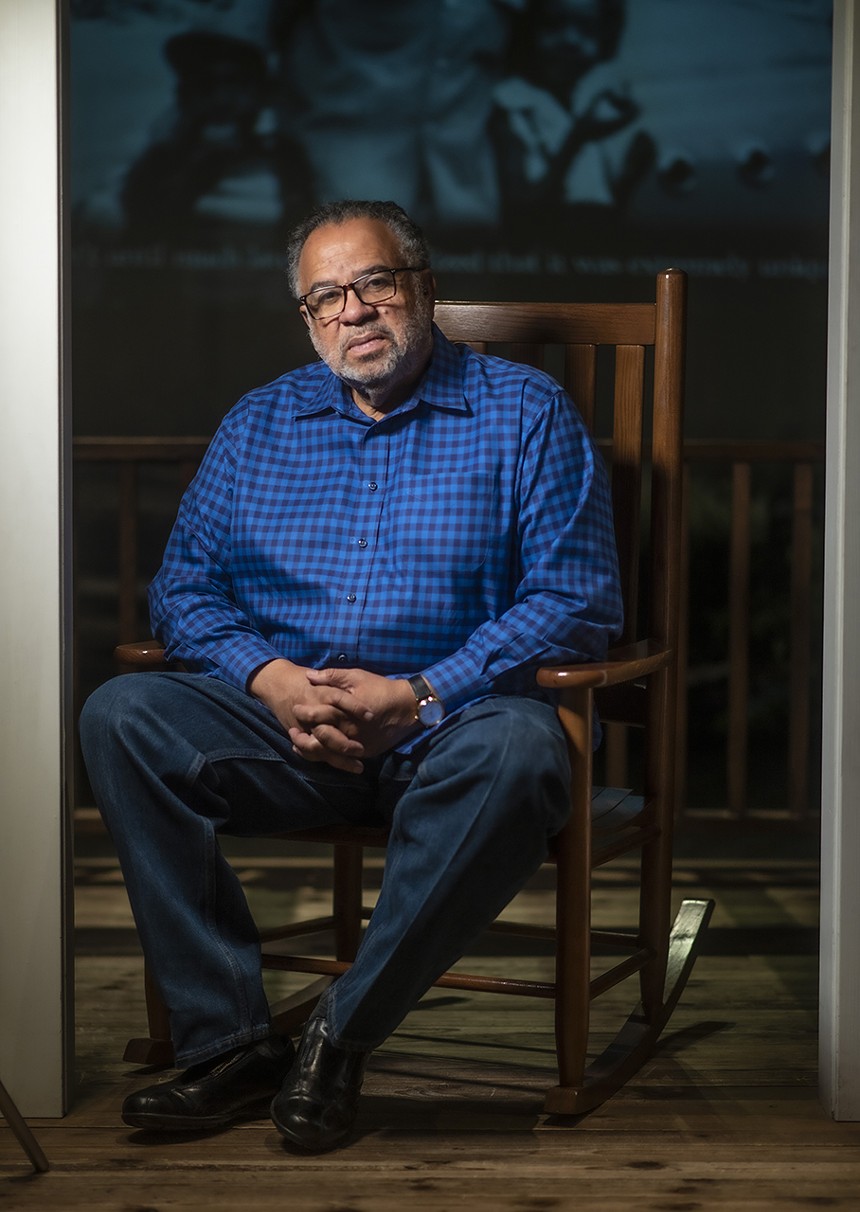

“A few years after his arrival in Colorado, he purchased several lots in Lincoln Hills,” says 76-year-old Gary Jackson, a senior Denver County Court judge who's the great-grandson of Pitts through Pitts's daughter, Elizabeth Pitts Scott. Pitts constructed cabins on those plots of land in unincorporated Gilpin County, and one remains in the family.

Over the last century, Lincoln Hills has weathered its share of misfortune, but today it stands as a testament to Black history — and a time when it was a refuge for a community banned from other vacation resorts. Its future is less certain, however; part of the property is now an exclusive, invitation-only club with a billionaire owner.

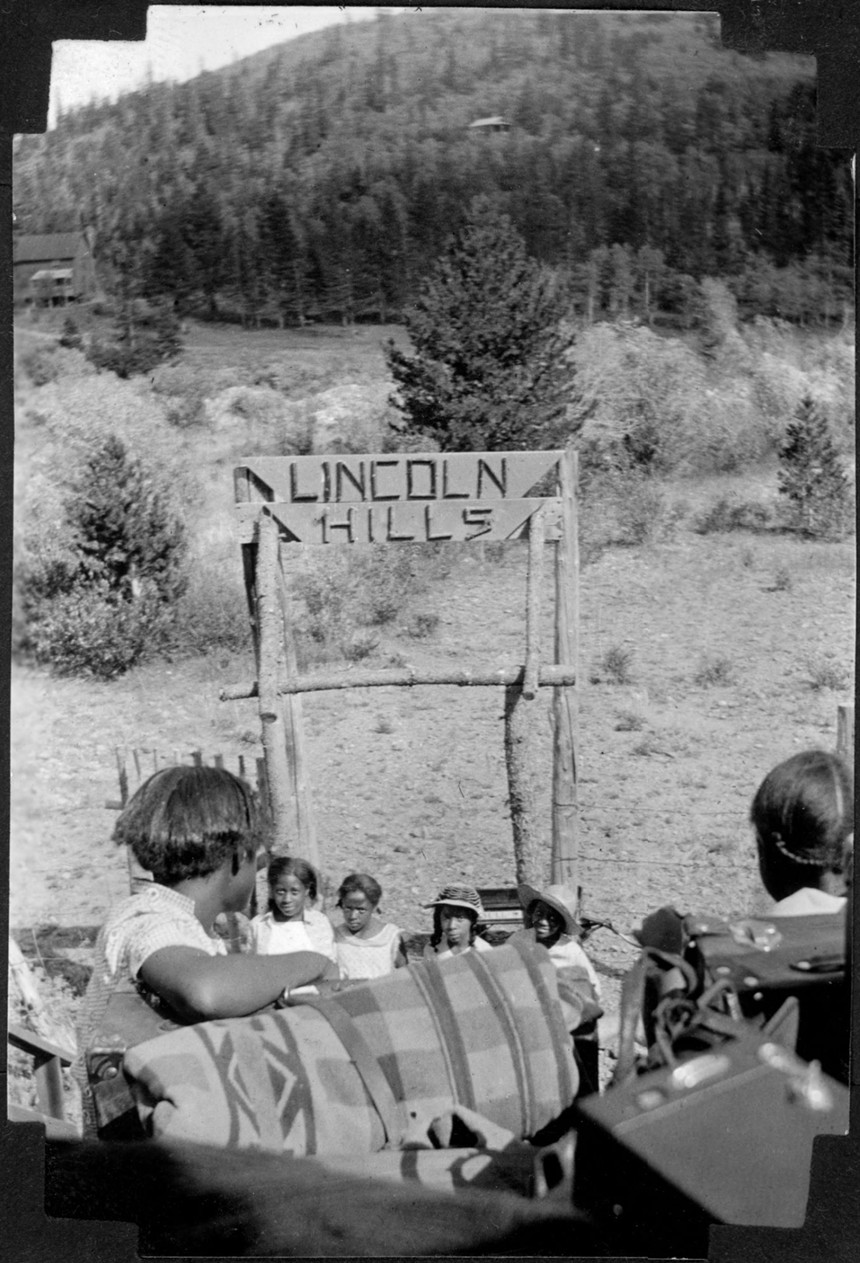

Lincoln Hills catered to Black families that were shut out of other resorts.

Denver Public Library Special Collections

"From what I've heard, the area had been previously dredged and was thought to be less desirable land," says Dexter Nelson II, associate curator of African-American history and cultural heritage at History Colorado.

"Really, everything up here in the ’20s was getting cheap because mining was way past its heyday at that point," adds David Forsyth, executive director of the Gilpin Historical Society.

Regnier and Ewalt acquired at least a portion of the property from Hal and Elizabeth Sayre, according to Melanie Shellenbarger's book High Country Summers: The Early Second Homes of Colorado, 1880-1940. Hal Sayre was a successful Denver businessman and Colorado's first professional engineer, who surveyed the early mountain towns of Aspen, Central City and Black Hawk, among others.

The two men plotted out around 1,700 lots in Lincoln Hills Country Club, with the concept of making a summer resort in the Rocky Mountains marketed specifically to Black individuals and their families, who weren’t able to access all-white resorts in places like Estes Park.

Despite the focus of Lincoln Hills, there's some debate over the race of its founders. “Some say they’re two Black men. There’s no indication that they’re African-American. The Census around the time says they were two white men,” notes Nelson, who acknowledges that Regnier and Ewalt might have been passing as white and actually of African-American descent. “We don’t know for sure. It’s definitely a gray area there on the ethnicity of those two gentlemen.”

But there was nothing gray about life in Colorado in the ’20s. The divisions between races were very stark.

“Context is really, really important for the s ory of Lincoln Hills,” explains Nelson. During the Great Migration, Black people in America moved from the South to the North, and also to the West, joining others who had already settled in the Rocky Mountain region. "During this period, you have Jim Crow and segregation. Also, you have 1915, which is the Birth of a Nation film, which really solidified the second wave of the Ku Klux Klan," he adds.

The Ku Klux Klan became extremely powerful in Colorado. Benjamin Stapleton, a KKK member, won the Denver mayoral race with the support of the Klan in 1923. Clarence Morley, another Klan member, was elected governor of Colorado in 1924.

For Black families that could afford it — the lots were small, 25 by 100 feet, and sold for anywhere from $5 to $100 — Lincoln Hills offered a welcome escape.

“It was really an oasis. You have all this negativity going on against Black and Brown bodies, and then you have this resort where people can be and fish and just enjoy the outside, which is very, very important,” says Nelson.

Pitts, a trained carpenter, built a family cabin on one lot and constructed others that he sold. He also began working on a mountain lodge that would become a focal point of Lincoln Hills Country Club.

Obrey Wendall “Winks” Hamlet opened Winks Panorama, aka Winks Lodge, in 1925. Hamlet was one of the original landowners at Lincoln Hills, and in the years that followed, the lodge and cabins he owned housed famous vacationing Black artists such as Duke Ellington, Lena Horne and Count Basie, who would sometimes come to the resort after performing in Denver.

While Hamlet brought the glamour, Pitts continued to boost the area. In February 1928, he penned a letter designed to persuade others to buy land in Lincoln Hills.

“The price asked for the lots seemed so ridiculously low that I feared the site must be inferior to others. But to my great surprise, I found it to be the most beautiful mountain subdivision that I have ever visited,” Pitts wrote.

But just as Lincoln Hills was starting to grow, the Depression hit.

“There were approximately 1,100 lots sold. But of those 1,100 lots, probably only twenty were actually built on,” says Jackson.

“It definitely hampered the growth of Lincoln Hills. But I don’t think it stopped it,” says Nelson.

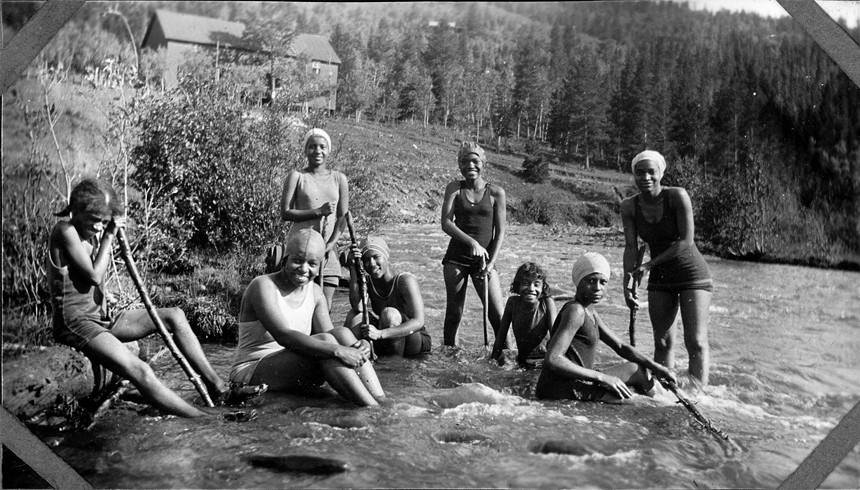

One of the main attractions at Lincoln Hills continued: an all-girls summer camp called Camp Nizhoni, which operated from 1924 to 1945. Since other camps in Colorado catered to a white-only clientele, Camp Nizhoni offered Black girls an opportunity to spend time in the outdoors.

“My mother actually attended the camp when she was about thirteen years old,” says Jackson, whose mother is now 97. “My mother has been diarying since the age of thirteen, so she has diary notes. She went to the camp by train, spent a week and returned home.”

The week was “a joyful period of time" that included “sitting around the campfires, singing songs, grilling hot dogs and hamburgers, and nature walks," according to Jackson.

Other people stopped by as they were touring the country. Lincoln Hills was a regular feature in the Green Book, which told Black travelers what places and services were safe and accessible. It was published from 1936 to 1967.

“Wondervu was considered to be a Jim Crow town. Rollinsville was considered to be a Jim Crow town. So travel was difficult, sometimes treacherous. Not only because of the narrow roads, but because of the attitude of the people,” says Jackson, 76. “Once you got to Lincoln Hills, it was an oasis, it was a safe haven. It was a unique experience once you got to Lincoln Hills.”

“The Klan was so strong for so long here, and the fact that this was untouched was very remarkable,” adds Nelson.

Lincoln Hills was definitely a summer destination. “At that time, you have to imagine, to get to Lincoln Hills, you’re talking about narrow dirt roads that were in some cases single-lane dirt roads, with hairpin curves. If you’re familiar with the weather in the Nederland and Pinecliffe area, back in those days, it would only be accessible by car only from Memorial to Labor Day,” Jackson says. A train line also ran right through Lincoln Hills.

Jackson's family, including many siblings and cousins, visited their Lincoln Hills cabin — named Zephyr View after the California Zephyr train that passed nearby — every weekend from Memorial Day to Labor Day.

“What you would do is fishing, hiking, mountain activities, swimming in the pond, throwing rocks into the creek, campfires — just recreational activities. We had room for volleyball, badminton, shooting our BB guns. Just mountain life, that was it,” Jackson says.

But just as the Depression had impacted Lincoln Hills, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 had a major effect. Suddenly other options were open to Black vacationers, and resorts like Lincoln Hills, American Beach in Florida and Idlewild in Michigan were no longer as important. The Green Book ceased publication, and many spots that had been featured in it closed.

After Winks died in 1965, his lodge shuttered. While some families held on to their cabins, Lincoln Hills Country Club was done.

"Because there were kind of safe spaces for Black people, I think you did lose a certain community, and community that went beyond the borders of the region," says Claire Oberon Garcia, a Colorado College professor who was recently appointed to the State Historian’s Council. "Certainly Lincoln Hills was part of that."

Lincoln Hills didn't disappear, though. Some people still lived in the area, a few year-round.

Ray Steele, now 82, moved from the Western Slope to the Front Range to find work in the logging industry. He rented a spot at Lincoln Hills in 1974, and in 1985 bought a cabin just down the road from Winks Lodge.

Back in its heyday, the cabin had been a watering hole for adults, a place where they could relax over some beers and cocktails. A light-up Coors sign still hangs high on the facade of Steele’s home, a tribute to the brew that was slugged there decades earlier.

The cabin was in pretty terrible shape when Steele bought it. From back to front, the floor had a 39-inch incline that he had to level out. “It was a shell. There was no water, no sewage,” Steele recalls.

Winks Lodge had fared better, because various owners had tried to preserve it through the years. In 2006, the James P. Beckwourth Mountain Club — named after the legendary Black mountain man — got a grant to buy the property from the Colorado Historical Society (now History Colorado) and applied to have it added to the National Register of Historic Places.

From 2007 to 2012, the Beckwourth Mountain Club kept the lodge open as a public museum and hosted fundraisers, reenactments and barbecues there.

The first year it was back open, Shelly Catterson, a writer and bookseller who lives two miles south of Lincoln Hills, attended a workshop at Winks Lodge. She fell in love with the area's history. “At that time, the Honeymoon Cabin was for sale, and I looked into buying it, because I felt strongly that it needed to be preserved,” recalls Catterson. The Honeymoon Cabin had been one of the options Hamlet offered his guests; by all acounts, Lena Horne had been particularly fond of the place.

Catterson added works of Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes to the shelves of the Honeymoon Cabin in a nod to some of the famous figures who'd visited Lincoln Hills. “And then Gary [Jackson] gave me a very nice collection of little photos that are all framed together of Lena Horne that has her autograph and stuff, so that’s very nice,” Catterson adds.

But Catterson wasn't the only person who became interested in Lincoln Hills.

Matthew Burkett, an entrepreneur who grew up in Evergreen and now lives in Five Points, also bought land in Lincoln Hills in 2007, with the goal of establishing a private fly-fishing club. He had an impressive partner: Robert Smith, a Five Points native who is now the wealthiest Black man in America; Smith's father used to visit Lincoln Hills. Together they purchased dozens of properties, including Winks Lodge, and built the Lincoln Hills Fly Fishing Club.

The Winks Lodge was built in 1925 and open for forty years; today it's part of the Lincoln Hills Fly Fishing Club.

Conor McCormick Cavanagh

Lincoln Hills Cares typically partners with community groups to bring kids from Denver up for the day. At Lincoln Hills, staffers guide them through a variety of activities, including lessons about outdoor survival, pond ecology and archery. Around 1,200 youth participate in the programs each year, according to Lapierre.

“Lincoln Hills itself, going back to the ’20s and ’60s, was a safe haven for Black people to get outdoors and recreate," he says. "For forty-plus years, [it provided] the opportunity to get out and go fishing and enjoy nature and what else it had to offer. And when you fast-forward into the 2000s, it is again a safe haven for providing opportunities for not only Black youth, but also Brown youth and other nationalities and genders and so forth. It’s remarkable how the location itself is still providing that opportunity, especially in this day and age, given all the political and racial issues and people of color marginalized, not venturing out into the outdoors. And we offer, still to this day, that great safe haven."

Smith and Burkett are “still catalysts and continue to be great resources financially, putting us and connecting us with organizations or individuals who want to donate,” says Lapierre, adding that the two are “not part of the day-to-day activities or anything like that.”

But they are definitely part of Lincoln Hills.

Smith has constructed a huge vacation home, complete with a tennis court, on property he owns next to South Boulder Creek.

Smith “has become a significant economic engine in Gilpin County," says Jackson. “From my perspective, Lincoln Hills has gone full circle, from when it was incorporated as the Lincoln Hills Country Club development to the present day, when the largest property owner is a Black billionaire.”

And Smith is continuing to buy property. “I’m just hoping that he’ll focus more on the history and restoring it instead of buying stuff up and leaving them,” says Catterson.

“This guy has not stopped construction since he got here,” adds Steele, who's selling his own home to Smith for far more than he paid for it.

Through a spokesperson, Burkett, who's faced criticism recently from business owners in Five Points over his work in the neighborhood, declined an interview request. Westword reached out to Smith through his company, Vista Equity Partners, but has not received a reply.

The creek that once hosted campers is now part of the exclusive Lincoln Hills Fly Fishing Club.

Denver Public Library Special Collections

It costs $700 a day to fish at the club, whose entrance boasts an electronic gate and a security guard.

“It so contrasts with the rest of Gilpin County," says Catterson. "I’m sure it’s the only gate with somebody actually monitoring it in the entire county.”

The club restocks the river with shipped-in trout every six weeks, according to Steele. “It’s just my humble opinion, but this is the dumbest fucking place for a fishing club,” he says, noting that South Boulder Creek is straight at that point, and not conducive to fish sticking around.

"It’s an odd mix around here, and the people who have been here for a long time, I think they kind of chuckle and shake their head and walk away from it," adds Forsyth. "The newer people, I think, get excited about it, and then sometimes they get burned out because sometimes things don't happen as quickly as they’d like."

Lincoln Hills was marketed as a place for Black vacationers who were banned from other resorts.

Denver Public Library Special Collections

"We knew Lincoln Hills was an undertold story," says Shannon Voirol, head of exhibits at the History Colorado Center. "We wanted very much to share the harsh realities of racism in Colorado and African-Americans' hard work to carve out a little rest and community in the face of that racism. We similarly worked hard to share the story of interned Japanese-Americans at Amache." The display devoted to that World War II internment camp in southeastern Colorado is just a few steps from the Lincoln Hills exhibit on the second floor of the building.

In February, History Colorado launched an initiative devoted to celebrating the centennial of Lincoln Hills. Last month it hosted a screening of director donnie l. betts's 2013 documentary about the historic resort. On June 3, Gary Jackson will offer a talk about the history of Lincoln Hills and his family’s connection to the area. There will be another event in August, and one or two more before the end of the year.

Nelson, who joined the History Colorado staff last year, visited Lincoln Hills for the first time in November and was “just blown away,” he says.

“It was kind of like a spiritual awakening, where I was like, ‘We’ve got to talk about this so much more. It’s great,’” he adds. “The legacy of Lincoln Hills has not diminished. It's still seen as this diamond in the rough."