The answer may have come just as the 2023 legislative session begins in Colorado, via a new study by the Colorado Fiscal Institute that attempts to illuminate a cost-benefit analysis of the oil and gas industry in the state to help inform policymakers.

“We really wanted to dig in and answer the questions like, how much benefits and tax revenue comes from the oil and gas industry in Colorado? And also pair that with the actual costs, things like air pollution,” says Chris Stiffler, senior economist for CFI and co-author of the paper. ”We always hear the industry is a huge part of our economy, and it's a huge part of our tax revenue, so what are the numbers?”

The CFI is a nonpartisan, nonprofit think tank; Stiffler describes it as the “wonky nerds” of Colorado. With Clearing the Air: The Real Costs and Benefits of Oil and Gas for Colorado, the CFI quantifies the industry’s impact on the economy. It also quantifies the industry’s cost to the state, including the costs of pollution, plugging old wells, and property values.

The study found that pollution emitted in oil and gas operations will cause over $13 billion in damages between 2020 and 2030. But it also extrapolates data from national research that found that health damages from premature deaths will be between $13 and $29 billion by 2026. Colorado’s share of that premature death cost: between $480 million and $1 billion.

"We always talk about the role of oil and gas in Colorado's economy, which is a very real role in today's world," says Pegah Jalali, research manager and co-author. "On the other hand, we just wanted to try to also quantify some of the costs associated with oil and gas to get a better picture, because these costs are also real. These costs are affecting other sectors of the economy."

Jalali notes that the oil and gas industry impacts tourism and agriculture, as well as the economy more broadly. For example, as she points out, those who die prematurely can no longer participate in the economy.

The study found that the oil and gas industry — including pipeline construction and other support industries — makes up 1.8 percent of wages in Colorado and 3.3 percent of the state’s gross domestic product. It represents 0.7 percent of the total employment in the state, with around 20,000 jobs.

The median wage of oil rig laborers in 2021, which offers the most recent data, was $46,740. That’s similar to the median wage in Colorado generally, which is $47,940. Drill operators, managers, business employees and engineers all make more than that.

Stiffler says that even as the oil and gas industry has shrunk in recent years, the state’s economy has grown.

“In 2018, oil and gas represented $18.5 billion in GDP in Colorado — 5 percent of the economy,” the paper describes. “In 2021, oil and gas represented $14.5 billion in GDP in Colorado — 3.3 percent of the economy. During the same period, Colorado’s GDP increased by 17.2 percent, while the oil and gas sector shrank by 21.4 percent. The overall positive trendline of Colorado’s economy during a time of decline for the oil and gas industry lends credibility to the idea that the state is not economically dependent on oil and gas.”

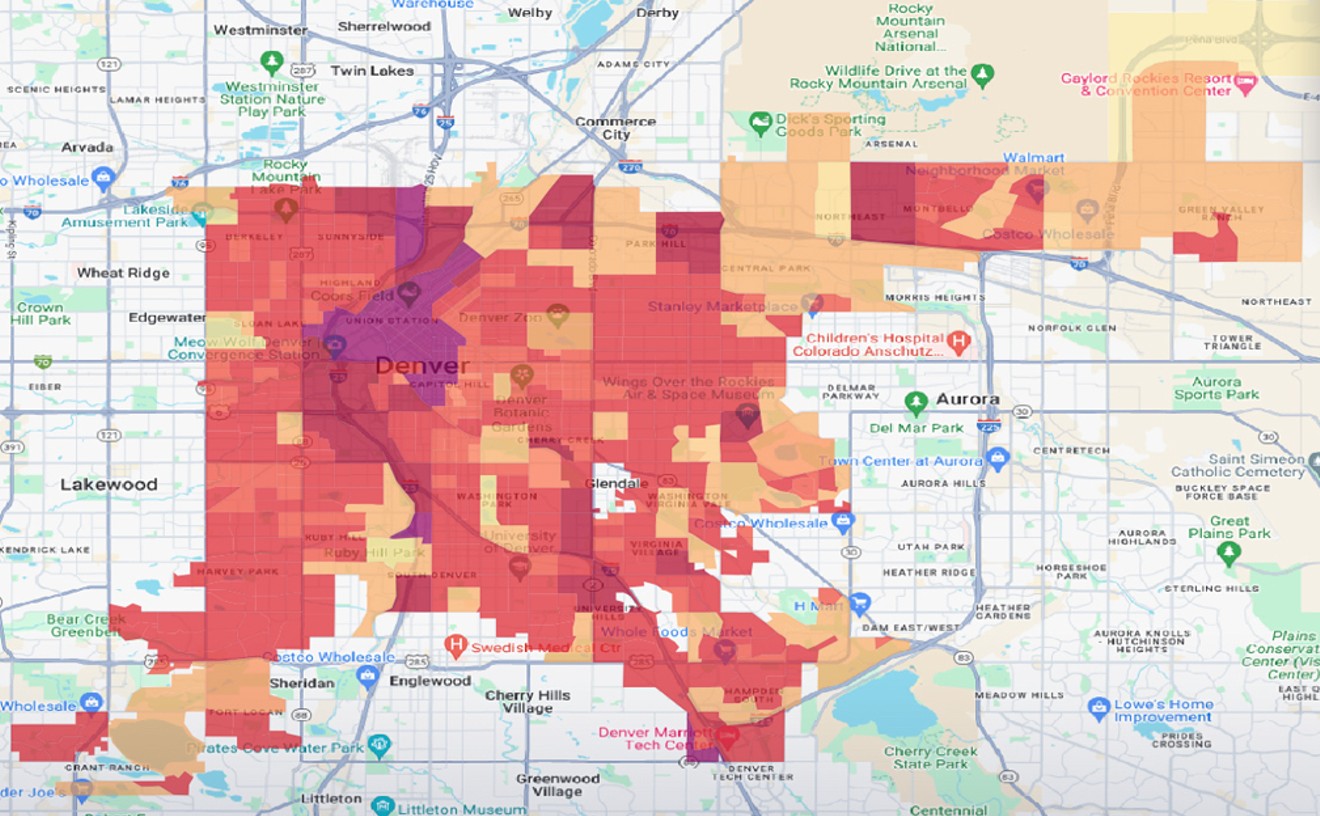

However, as Stiffler notes, some areas are more dependent on oil and gas than others. The study helps identify those areas, calculating how much property tax each county in the state received from properties assessed as oil and gas. In total, the oil and gas industry contributed $621 million in property taxes in 2021.

Nine counties received more than 10 percent of their property taxes from oil and gas, with Dolores County the highest, at 61.3 percent. The next four-highest counties are Montezuma, Weld, Garfield and Rio Blanco, with around 40 percent each. Some of those property taxes go toward funding schools, but 84 of the 178 school districts in the state have zero oil and gas-related funding.

“It does highlight the fact that if we do transition from oil and gas, we need to be thoughtful about, in the state, finding ways to backfill those local governments,” Stiffler says. There is already a backfilling mechanism in place for schools in the form of the school finance formula that compensates for property wealth disparities; according to the study, that would cover about half of the lost property taxes currently contributed by oil and gas. “What doesn't have backfill is county debt budgets, city budgets, fire districts, override dollars and school finance,” Stiffler adds.

The study also suggests that the state should consider the detriments of oil and gas when it considers the path forward.

"There are other health damages, including cancer and respiratory problems, heart diseases, because of that air pollution and as a result of oil and gas production," Jalali says. "One damage is to human health. The other is damages to the environment, like loss of habitat or fragmentation of habitat, loss of biodiversity, pollution of groundwater sources."

Pollution contributes to global warming, as well. Climate-caused disasters have cost the state between $20 and $50 billion since 1980. Ozone precursors also will be costly, with the study projecting that in 2025, cleaning up nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds released into the atmosphere will cost between $100 and $180 million.

“These significant costs are borne by Coloradans, especially those communities sited nearest the oil and gas developments, which research shows are more likely to be communities of color and places where people are more likely to earn low incomes,” the study asserts.

Property values are negatively affected by oil and gas operations, too, with the paper revealing a general decrease in property values in close proximity to oil and gas. For the Western Slope, which the study considers the counties of Garfield, Mesa and Rio Blanco, houses within one mile of a drill site sold for 34.8 percent less than comparable properties with a lower proximity to drilling.

As the state continues to tackle questions around climate, health and just transition — attempts to equitably ensure that no communities get left behind as the state explores alternative energy and remediation solutions — at the legislature, Stiffler and Jalali say that accurate data about the oil and gas industry will help. In 2019, the CFI worked on the Climate Action Plan to Reduce Pollution; this year, it's already jumping in on a bill sponsored by Senator Chris Hansen and Representatives Karen McCormick and Emily Sirota to contribute knowledge on the oil and gas industry as it relates to greenhouse gas emission reduction.

“We wanted to add the real cost and real benefits into the same discussion,” Stiffler says. “A lot of times, it's siloed. … We really wanted to take the publicly available data and put it out there so we can have a more informed discussion about a just transition.”