“He was part of some local mythology, but nothing that was formally taught,” recalls Torres, the city council representative for Denver’s west side since 2019.

Supposedly, Barnum pastured elephants, giraffes and other members of his traveling menagerie in the area during the off-season, before there were any houses there. Another version, one that still circulates on hiking websites, has it that the real winter home for P. T. Barnum’s circus animals was located at what is now Meyer Ranch, a popular recreational area in the foothills. Then there’s the one about the elephants being employed to push Barnum’s circus train over Boreas Pass. The stories don’t make much sense — why would a circus train be on Boreas Pass? Why would the elephants be pushing instead of pulling? Why would anyone stash circus animals in Colorado for the winter? — but logic never got in the way of a good Barnum story.

For several years, a man claiming to be Barnum’s great-great-grandson offered tours of a house on King Street, which he called the Barnum House. But the family tree didn’t check out, and Barnum never lived in the Barnum House. In fact, Barnum never lived in the Barnum neighborhood at all. He visited Colorado only four times between 1870 and 1890, to visit his daughter and check on his real estate investments in Denver and Greeley.

The local lore about Barnum has been debunked repeatedly by researchers over the years. But it’s recently come under scrutiny again, thanks to a proposal by the Denver Public Library to remove Barnum’s name from the Ross-Barnum Branch Library, in the heart of the Barnum neighborhood. (The name of Frederick Ross, a pioneering Denver businessman and DPL donor, would remain, joined to whatever local figure is chosen to replace Barnum.) At issue isn’t simply Barnum’s tenuous connections to the community, but his treatment of people with disabilities and people of color during his rise to fame and fortune. DPL officials have declared that the Barnum name “does not align with the library’s own values.”

The proposal is part of a reckoning process undertaken by city agencies in the wake of the 2020 murder of George Floyd. The process requires a review of city assets, with the aim of determining whether certain once-celebrated figures should be canceled or condemned. Eighteen months ago, DPL removed the name of William Byers, founder of the Rocky Mountain News, from a branch library, citing his keen support for the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre, a U.S. Army attack on a peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho encampment that killed more than 200 people, mostly women and children. That library is now the John “Thunderbird Man” Emhoolah Jr. branch, in honor of an Indigenous activist and descendant of Sand Creek survivors.

This time around, DPL is proceeding more tentatively than it did in deposing Byers. It is surveying area residents for opinions on the proposed name change; if not enough people feel strongly about Barnum, the name may not be changed at all. “We’re thinking about this, not as erasing history, but reframing history,” says Erika Martinez, DPL’s director of communications and community engagement. “We don’t have to change every name, but we can at least inform the community of the history and give them the opportunity to provide feedback.”“We don’t have to change every name, but we can at least inform the community of the history.”

tweet this

Chala Mohr, vice president of the Community Coalition for Barnum, says there was “mixed feedback” at the neighborhood group’s recent meeting on the proposed name change. “There’s definitely not a consensus or a position that we’ve taken,” she says.

Councilmember Torres says a few constituents have told her that the library will always be “Barnum” to them. “For some of them, it’s the only name they’ve known,” she notes. “The library’s research uncovered stuff I didn’t know. I will go the direction of the community, but personally, I feel we could look at some really wonderful people and legacies for the name of this facility.”

Martinez expects that the survey results will be compiled in the next week or two. If a decision is made to proceed with the name change, she adds, it could be implemented while the branch is closed for renovation later this year.

But the library isn’t the only institution bearing the Barnum name; there’s also a park, a recreation center, an elementary school, and several other going concerns that happen to be named after the neighborhood in which they’re located. That name may resonate with members of the community for reasons that have nothing to do with the legacy of Phineas Taylor Barnum, a legacy that is about as easy to grasp as an elephant pushing a train up Boreas Pass.

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, P.T. Barnum was arguably the most famous person on the planet. His tours of Europe with attractions in tow, his traveling circus shows, his sensational museum in the heart of New York City, his brazen publicity stunts and best-selling, periodically updated autobiography all helped to catapult him to international celebrity. According to Robert Wilson’s Barnum, a 2019 warts-and-all study of the showman, when former President Ulysses S. Grant returned to America after two years on a world tour, Barnum praised him as “the best-known American living.”

Grant disagreed. “You beat me sky-high,” he said. “Wherever I went…the constant inquiry was, ‘Do you know Barnum?’”

Do we know Barnum? The popular image of the man is soaked in hokum and tall tales, some of them circulated by Barnum himself in his relentless quest to bamboozle the public and the press. Hollywood has helped perpetuate the myth, embracing and embellishing it — most recently, in the version of Barnum played by Hugh Jackman in the 2017 movie musical The Greatest Showman, a largely fictitious account of P.T.’s struggles, romances and triumphs.

For the record, there’s no evidence that Barnum ever uttered the phrase “There’s a sucker born every minute,” the quote most often attributed to him (though he probably would have seconded the sentiment). He didn’t launch his renowned circus until he was in his sixties. He doesn’t seem to have had a fling with Swedish soprano Jenny Lind.

The historical Barnum is a more complex and problematic figure than the legend. He could be courageous and inspiring, hypocritical and devious. He was a master of hype and a pioneer of mass entertainment, and his behavior could be crudely exploitive and appalling. But he was also, at various times, a crusading newspaper editor, a state legislator, the mayor of Bridgeport, Connecticut, and a passionate advocate of abolition and the temperance movement — details that are mostly missing from the Denver Public Library’s online summary of Barnum’s “complicated past.”

Kathy Maher, executive director of the Barnum Museum in Bridgeport, says that her organization welcomes public discussion of Barnum’s legacy. His achievements are more extensive than most people realize, she adds, from introducing working-class American audiences to opera and ballet to donating thousands to improving animal welfare, long before the cause became fashionable.

“Barnum had his critics,” Maher says, “but he had a lot more people who supported him, from all levels of society. You have to look at his life through the lens of what the world was like almost 200 years ago. We’re not trying to sanitize him, but he came through some tough times and left the world a better place.”“That’s where fact and fiction get blurred. There’s a lot of that with Barnum.”

tweet this

Born in Bethel, Connecticut, in 1810, Barnum grew up in a Yankee family of modest means. By the age of twelve, he was peddling lottery tickets and running his own candy concession at a family general store. In his early twenties he started a newspaper, the Herald of Freedom, and was promptly sued for libel three times. But it was another venture from his money-hungry youth that has triggered the most red flags among those seeking to rename the Ross-Barnum library.

In 1835, Barnum learned of an investment opportunity: An aged, enslaved Black woman named Joice Heth was being exhibited in country inns, city dance halls and other venues as “one of the greatest natural curiosities ever witnessed.” Heth’s claim to fame was twofold: She was said to be 161 years old, and to have been George Washington’s nursemaid.

Barnum went to Philadelphia to catch Heth’s performance. He saw a blind, toothless, emaciated and partially paralyzed woman who sang hymns and spoke fondly of “dear little George.” Convinced that he could do a better job of promoting Heth than her current handler, Barnum scrounged and borrowed a thousand dollars to obtain the right to exhibit her for one year. Technically, he wasn’t buying a slave, but he was renting her.

Barnum and his star attraction embarked on a demanding tour of cities in both free and slave states. Public outcry over the shameful display of an elderly woman greeted them on occasion, but the crowds kept coming. When interest slumped, Barnum revived it by planting stories that hinted Heth wasn’t a real person but an automaton, constructed of whalebone, rubber and springs. In six months, Barnum made an estimated $10,000 from the enterprise and realized that he had “at last found my true vocation.”

Then Heth fell ill and died at Barnum’s brother’s house in Bethel. Her service to Barnum was not yet concluded, though. The great showman announced that there would be an autopsy to resolve the public’s curiosity about Heth’s true age. According to some accounts, Barnum rented a New York theater for the event and sold tickets, at fifty cents each, to 1,500 ghoulish gawkers; Maher says that isn’t true. Reporters, medical students and clergy were invited to attend, but Barnum didn’t sell tickets to the public. “That’s where fact and fiction get blurred,” Maher says. “There’s a lot of that with Barnum.”

Barnum glosses over this sordid business in his autobiography. He opines that Heth’s true age will remain a mystery (the doctor who conducted the post-mortem estimated that she was around eighty). He insists the arrangement he negotiated to take over the exhibiting of Heth as the world’s oldest human was “a scheme in no sense of my own devising.” Barnum biographer Wilson views the episode as possibly the most troubling in Barnum’s long career: “He would never be able to escape the cost to his reputation, despite later efforts to improve himself and his approach.”

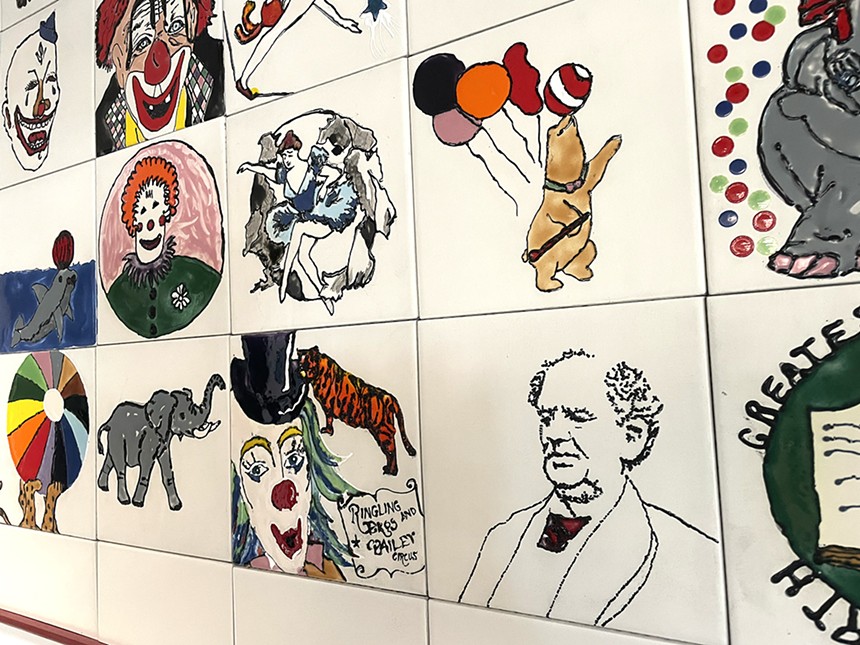

Promoter P.T. Barnum bought property west of Denver that was incorporated as the town of Barnum in 1887.

Denver Public Library

Among Barnum’s discoveries were Charles Stratton, better known as General Tom Thumb, a two-foot-tall child who had basically stopped growing when he was six months old; eight-foot "giantess" Anna Swan; and William Henry Johnson, a microcephalic Black man, billed as Zip the Pinhead. He even lured Eng and Chan Bunker, famous conjoined Siamese-American twins, out of retirement. Barnum’s detractors contend that his marketing of these “curiosities” demeaned people with disabilities and trafficked in racist stereotypes, portraying Indigenous people as bloodthirsty savages and Johnson as some kind of evolutionary mistake.

Yet it would be misleading to characterize Barnum’s treatment of his human attractions as mere exploitation or “othering.” Under Barnum’s tutelage, Stratton demonstrated great skill as an actor, eventually garnering notices that focused on his talent rather than his height. He went on to manage his own career and became quite wealthy, even bailing Barnum out after one of the showman’s financial disasters. Johnson had a successful career in show business that spanned sixty years. Barnum may have pandered to the public’s morbid curiosity, but he also gave his stars economic opportunities in a world where most doors were closed to them.

In his own bombastic way, Barnum tried to make amends for exhibiting Heth, too. He became an ardent Republican and pushed as a state lawmaker for Black enfranchisement in Connecticut. His outspokenness may have led to a suspicious fire that destroyed his New York museum in 1865. The cause of the fire was never proven, but Confederate sympathizers had targeted the structure before and may have been the culprits.

After the loss of the museum, Barnum’s good friend Horace Greeley advised him that it was time to go fishing. But Barnum wasn’t ready to retire. He would rise from the ashes again and again, working on the Greatest Show on Earth and related projects, until his death in 1891. His name would live on, along with many stories about his exploits that simply weren’t true.

“When he died, he didn’t have anyone to polish his brand,” Maher notes. “His actual story kind of got lost.”

The most reliable record of Barnum’s Colorado adventures can be found in, of all places, the archives of the Denver Public Library. A special collection devoted to Barnum includes more than a hundred letters he exchanged with his lawyers and business associates dealing with his vexatious investments in the Centennial State and related catastrophes.

Barnum first came to Colorado in the early 1870s to deliver temperance speeches and inspect the Union Colony, a utopian farming community that would soon evolve into the town of Greeley. Over the next few years he acquired a ranch south of Pueblo, several lots in Greeley’s business district and 765 acres on the western outskirts of Denver, which he figured would soon be needed for expansion of the rapidly growing city. He had high hopes.

“I have made more money in the rise of real estate than in all other ways put together,” he boasted to his Greeley attorneys. “My investments in Colorado are made with the idea of immense returns after a while.”

But even pint-sized returns were hard to come by. The letters are full of fretting over deadbeat tenants, untrustworthy partners and prospective buyers who are all hat, no cattle. He set up a tubercular, alcohol-imbibing son-in-law, William Buchtel, in business only to endure complaints from his daughter Helen about her desire to leave Colorado. (Buchtel’s brother Henry later became the chancellor of the University of Denver, Colorado’s governor, and the namesake of Buchtel Boulevard.)

Barnum had snatched up his property west of Denver sight unseen for a few thousand dollars, with the expectation that it could be worth as much as $200,000 to an ambitious developer. But the area was hilly, muddy and forbidding; after a few months, Barnum was willing to unload his investment for half that price. He still had no takers. He flirted with the idea of selling it to Denver as parkland, but he didn’t have the juice with local officials to make that happen. Initially charmed by the city’s fine air and scenery, he became increasingly pessimistic about getting a fair shake from the locals.

“I know Colorado (& especially Denver) swarms with unscrupulous sharpers even in the courts & holding official positions,” he wrote in 1878.

Barnum prided himself on being the prince of humbug, the baron of ballyhoo. His come-ons, like the Fejee mermaid, may have been the nineteenth-century equivalent of clickbait, but he insisted that people wanted to be fooled — and that nobody ever left his attractions without feeling entertained. But he was out-humbugged by the sharpers in Denver. After several years of frustration, he decided to throw in the towel.

He parceled out what lots he could and turned the rest over to his daughter for one dollar. The town of Barnum was incorporated in 1887, but within a few years, most of it had been annexed by Denver.

The former township was officially designated the Barnum neighborhood (though portions of what had once been Barnum's holdings became part of the West Barnum and Villa Park neighborhoods). Originally envisioned as an enclave for the wealthy, Barnum evolved as a multicultural, working-class area that was (and still is) one of the most affordable neighborhoods in the city.“Denver swarms with unscrupulous sharpers even in the courts.”

tweet this

Doubtless there are many local trailblazers worth celebrating who have stronger roots in that community than Barnum himself, an absentee land speculator. (Asked if she had any nominations for the library name, Torres suggested Lucile Buchanan, a former Barnum resident and the first Black woman to graduate from the University of Colorado.) Even so, Barnum has a persistent claim on the locals, too. Quite apart from the historical significance of his many contributions to American culture — as the progenitor of mass entertainment, the pseudo-event, viral messaging, yada yada — there’s the matter of his bitter education in the boondoggles of Colorado real estate.

Like somebody once said, there’s one born every minute.