"The sad reality is that six is probably still not enough just to meet the need of individuals who are dealing with opiate use," CMS regional manager Jesus Godinez says.

CMS currently operates one clinic in Aurora, at 14300 East Exposition Avenue, which opened in October 2022. According to Godinez, expansion has been in the works since 2023. Englewood, Sheridan, Greenwood Village, Westminster, Lakewood and Northglenn will all have new CMS opioid clinics by the end of September, he says. The first clinic will open in Englewood at 4384 South Federal Boulevard on Tuesday, July 30, with the next five openings in successive weeks.

The clinic treats people by offering methadone and Suboxone to deaden cravings and highs, and providing counseling and therapy to walk through recovery. Frazer Grant, the medical director for CMS, says methadone and Suboxone are used for "medication-assisted treatment" alongside counseling because it's proven to be more effective.

"When you combine the medicine with counseling and behavioral therapies, it's been shown to be really effective in helping individuals achieve a long-term recovery," Grant says. "The goal of methadone or Suboxone treatment is to get rid of the withdrawals so a patient can wake up in the morning and feel well, and not have to get what they need to stay well."

Methadone therapy can reduce the risk of death related to drug use by about 50 to 80 percent, Grant says. Patients usually come in three days a week for methadone or Suboxone at the clinic; once counselors see that they're steadily recovering, they come once a month and take the medications at home.

The counselors at CMS are meant to help clients talk through their recovery, supervise withdrawals and wean them into lower doses of methadone or Suboxone, which are also opioids, but with more manageable effects, according to Grant.

The clinic treats people by offering methadone and Suboxone to deaden cravings and highs, and providing counseling and therapy to walk through recovery. Frazer Grant, the medical director for CMS, says methadone and Suboxone are used for "medication-assisted treatment" alongside counseling because it's proven to be more effective.

"When you combine the medicine with counseling and behavioral therapies, it's been shown to be really effective in helping individuals achieve a long-term recovery," Grant says. "The goal of methadone or Suboxone treatment is to get rid of the withdrawals so a patient can wake up in the morning and feel well, and not have to get what they need to stay well."

Methadone therapy can reduce the risk of death related to drug use by about 50 to 80 percent, Grant says. Patients usually come in three days a week for methadone or Suboxone at the clinic; once counselors see that they're steadily recovering, they come once a month and take the medications at home.

The counselors at CMS are meant to help clients talk through their recovery, supervise withdrawals and wean them into lower doses of methadone or Suboxone, which are also opioids, but with more manageable effects, according to Grant.

The expansion of opioid clinics is "fantastic" and desperately needed in the Denver metro area, says Jose Esquibel, associate director of the Colorado Consortium for Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention. The consortium is supported by and headquartered at the University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, and is responsible for coordinating Colorado's statewide response to the opioid crisis.

"We just don't have enough of these services," Esquibel says. "We have a high need. We just don't have the full capacity to meet the full need of people who want these services. So this is really good news."

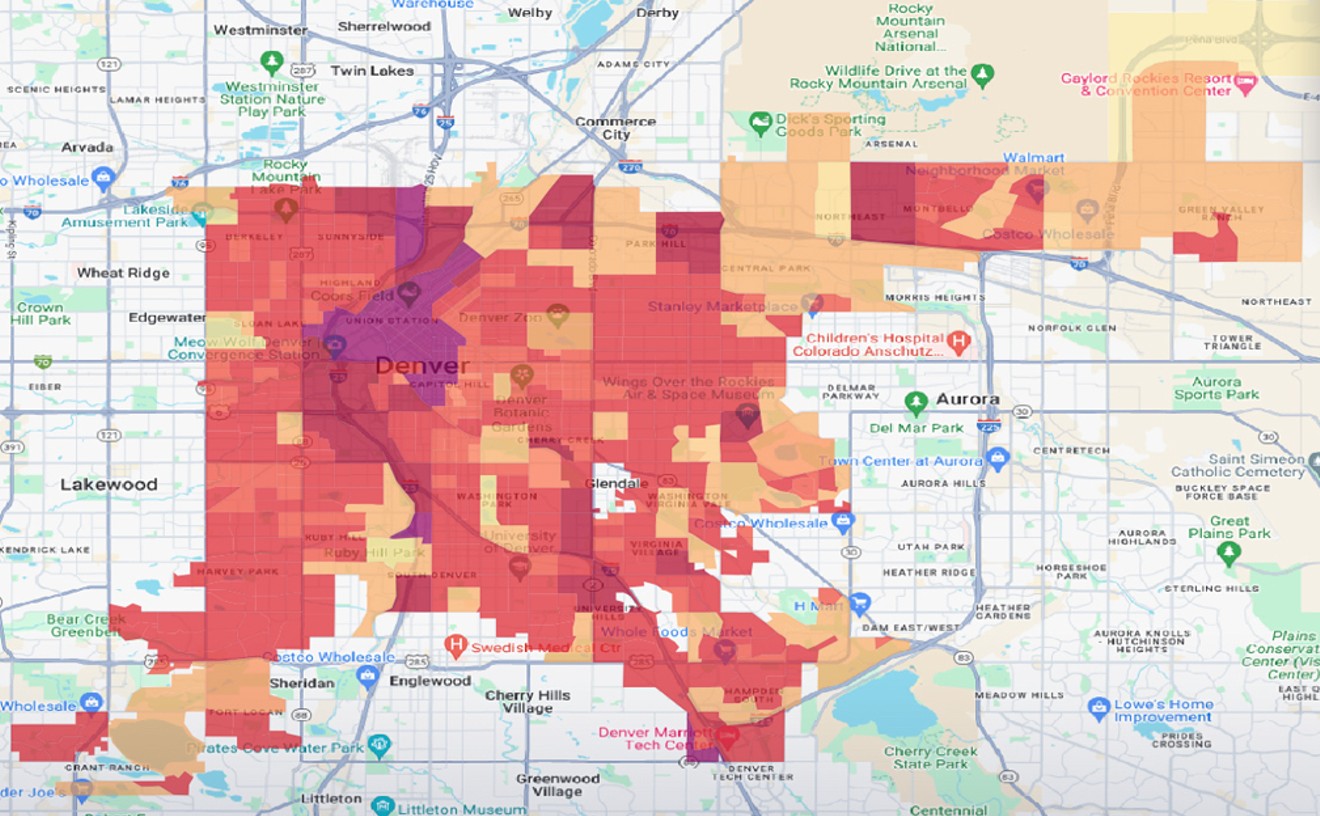

Colorado's highest rates of opioid deaths are in the Denver metro area, Esquibel notes. "So if we can do more in Denver to reduce the number of [opioid] overdose deaths, we will drive the overall state rate down," he says.

Esquibel calls the metro area a "treatment desert" where people can't find opioid clinics for miles. The eastern metro area in particular has "a huge gap" of services in areas like Aurora, Northglenn and Greenwood Village.

"Anywhere in the city that we can offer these services, they're going to be important for people. We don't need people having to go hours on buses or driving through town trying to find the service provider," Esquibel says. "We need to have them linked up to services that are convenient to them. "

Colorado saw a steady rise in annual opioid-related deaths before 2020, from 269 in 2010 to 620 in 2019. But those numbers have increased even more in the 2020s as fentanyl use and overdoses rise. In 2020, Colorado suffered 958 opioid deaths, and totals have stayed between 1,100 and 1,300 per year since 2021, according to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment.

Community Medical Services, a national organization, is opening six opioid clinics to keep up with a high local demand for addiction treatment.

Bennito L. Kelty

Opioid deaths increased but quickly plateaued in Colorado after 2020 because of improvements in overdose prevention, Esquibel says. "We have folks out there that are using daily that are not overdosing, or if they are overdosing, they're being reversed with Narcan or naloxone," he says.

Addiction is harder to track, however.

Addiction is harder to track, however.

"We don't have the best count of the number of people who actually need treatment...but it's high. The percentage of people with an addiction in Colorado, that's pretty high, and as far as the ability to serve all those people, it's not enough."

Estimates of people seeking treatment nationwide range 2 to 3 million, according to the National Institute of Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse — but those estimates "won't tell you how many people need treatment," Esquibel says.

Fentanyl-related overdoses are largely driving the increase in opioid-related deaths in Colorado, going from 540 in 2020 to nearly 1,100 deaths in 2023. That marks a jump from 2019, when Colorado recorded 222 deaths from synthetic opioids, including fentanyl and prescriptions, and only 102 such deaths in 2018, the first time that number passed 100.

Since 2020, fentanyl-related overdoses have overtaken heroin as the main overdose opioid, CDPHE data shows. In 2020, fentanyl caused more than half of Colorado's opioid deaths — about 56 percent — for the first time. By 2023, it accounted for 85 percent of statewide opioid deaths.

Colorado has recorded 403 opioid deaths so far in 2024, according to the CDPHE, but the department is often months behind accurate numbers because of the time required to determine causes of death. Of those 403 deaths, 326 were related to fentanyl.

"It's really hard to get off fentanyl because it's extremely addictive and potent," Grant says. "It changes the chemistry and structure of our brain, so it's even harder to get off. And when one stops using fentanyl, you get a very severe withdrawal syndrome that's very difficult to manage without professional help."

Grant says that "fentanyl is replacing other opiates" and "heroin is getting harder and harder to find." This is because fentanyl is "fifty to a hundred times stronger than heroin" and "is perfectly packaged and marketed," he explains.

"For the vast majority of people using fentanyl on the street, it's illicitly manufactured little pills. They're often referred to as 'blues,'" Grant details. "When you compare that to heroin, it's quite an innocent-looking pill compared to the tar of heroin."

Fentanyl is used in hospitals to treat pain, but most of the clients that Grant treats at CMS are using the pills sold on the streets. They also use a powder form they can smoke, he says.

Esquibel says that the rate of opioid deaths in Colorado is not as bad as other states, but that the state ranks in the middle of the pack. "We're not as good as other states," he says. "But our numbers have climbed."

Godinez says that for CMS to meet the need for opioid addiction services, it would have to open another six clinics, at least.

Colorado state health officials have been trying to expand opioid treatment centers, especially those with methadone services, for the past four years, Esquibel says. So far, the state has seen "a good increase" in those centers, but it hasn't seen an organization expand as quickly as CMS is now.

Other opioid clinics in Colorado that offer methadone include Addiction Research Treatment and Services (ARTS), Colorado Treatment Services, the Behavioral Health Group (BHG), Crossroads and Denver Recovery Group.

"We need more," he says. "There's no doubt about it. We need more. ... There's plenty of room for expanding these programs, especially in the city where you have the highest population base. We're just not meeting the treatment demand with the population that we have. These are services that are really important. The more access, the better."

"We need more," he says. "There's no doubt about it. We need more. ... There's plenty of room for expanding these programs, especially in the city where you have the highest population base. We're just not meeting the treatment demand with the population that we have. These are services that are really important. The more access, the better."

Treatment at most opioid clinics isn't free, but the majority of clients pay through Medicaid, which is health coverage paid with state and federal tax dollars. CMS is in the process of getting credentialed through Medicare, which is publicly funded health coverage for seniors. The cost of services typically ranges from $42 to $84 a week, based on a client's income.

Godinez says that even if the number of opioid deaths starts to decline, opioid addiction is a life-long struggle, and people in recovery still need clinical services to continue to maintain sobriety.

"We need to ensure that those individuals who are coming out of treatment, how do they not relapse?" Godinez says. "How do they have the tools and resources they need to be successful post-treatment?"