“Right now, I think we all agree that our behavioral health system is absolutely broken,” says Michelle Barnes, executive director of the Colorado Department of Human Services and a leader of the task force.

Governor Jared Polis announced the Behavioral Health Task Force in May. Lieutenant Governor Dianne Primavera, who is on the executive committee of the task force, has said that mental health was one of the most prominent concerns she and Polis heard from Coloradans while traveling during the campaign, and that behavioral health (an umbrella term encompassing both mental health and substance use disorder) will be a priority for the administration.

The task force’s goal is to create a statewide strategic plan by June 2020, with specific annual deadlines for certain actions and an outline of who can be held accountable for getting them done. It will also aim to help the state better integrate its behavioral health and physical health services. Subcommittees will focus on children's behavioral health, competency procedures in the criminal justice system, and the state's safety nets.

“This is an opportunity to make systematic transformation,” Barnes says. “I'd like to see us do a complete overhaul. I will be really disappointed if we come back with just a few incremental changes.”

Summer Gathercole, an advisor for the task force, acknowledges that systematic change is not going to be easy. “We have a huge system with different stakeholders at different levels,” she explains. Currently the state administers behavioral health services to various populations through at least three departments, including Corrections, Health Care Policy and Financing, and Human Services. Counties and municipalities also provide varying levels of services. Then there are private mental health providers, which sometimes work in conjunction with public entities. Given all that, Gathercole says, the task force is open to looking at whether bureaucratic reshuffling or other out-of-the-box approaches are necessary.

“We aren't lacking…people who are passionate about this,” Barnes says, adding that the executive committee was both excited and overwhelmed when over 500 people jumped at the chance to volunteer time and energy to the cause and nominated themselves to join the task force. “What I'm seeing is a lack of connecting the dots.”

One of the challenges the committee may face is determining how to tackle the root of the problems. While it’s abundantly clear that Coloradans have comparatively low mental health and face comparatively high rates of substance abuse, it’s not exactly clear why. As Jalyn Ingalls, a behavioral health researcher at Colorado Health Institute, explains, the prevalence is almost certainly underreported, since not everyone who experiences mental health illness or substance abuse seeks help or self-reports it. And it’s hard to measure access to mental health services, too, since researchers have different metrics for what kind of access — at what cost, frequency and availability — counts as adequate.

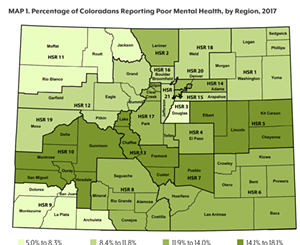

According to Mental Health America’s 2018 report, Colorado actually ranks comparatively well — 17th in the nation — in terms of access to mental health services, though there are major disparities in rural versus urban areas and among less advantaged socioeconomic levels and racial groups. Yet the state has the second-highest prevalence of mental health illness overall.

Residents of the darker green counties reported higher rates of poor mental health, defined as experiencing eight or more days of poor mental health.

Colorado Health Institute

One theory as to why — which, according to Ingalls, doesn’t have quite enough scientific backing yet to confirm — is that mountainous regions exist in a “suicide belt” because high altitudes impede brain function in such a way as to increase risk of depression and suicide. Another theory is that the "suicide belt" also mostly consists of hunting states, and thus there are more firearms — but that doesn't explain the high initial rates of depression and mental illness. Other research points to a "pick-yourself-up-by-the-bootstraps" mentality in the rural West that can stigmatize seeking help.

Other possible explanations for the high prevalence of behavioral health include Coloradans' affinity for both legal substances (alcohol, marijuana) and a growing use of illicit substances such as cocaine and opioids. The most recent data indicates that Colorado leads the nation in consumption of all four substances, and in some cases even “responsible” use can increase the risk of poor mental health. A recent report also found that access to medicated assisted treatment for substance abuse is particularly low in Colorado.

Joe Hanel, Colorado Health Institute's director of communications, points out that especially in the past few decades, Colorado’s population is increasingly transient and its residents are disconnected from their support networks: Denver has boomed with newcomers who “just don’t have those social connections” within the state, while rural communities have experienced an outward migration and thus are left without people around.

Regardless of the mysteries in the background, researchers say, it’s clear that Colorado could be doing more to help people get the services they need — especially in rural areas, tribal communities and communities of color, as well as for those who are unemployed, uninsured or underinsured.

That’s something that Primavera, who worked as a vocational rehabilitation counselor for twelve years before her career in politics, understands well. “Who you are is determined by what you do, and so when people are mentally ill and don't have a job, it really impacts what they feel about themselves as human beings,” she says.

Barnes says the task force will look to other states to see what they’re doing that Colorado isn’t. And it will hit the ground running, attempting to get enough information, resources and plans together to be able to influence bills in the 2020 legislative session.