Forty years ago, Bill McCartney was the new football coach at the University of Colorado Boulder. In 1990, he led the team to its only national championship victory, then left CU four years later.

Since then, the school hasn’t found a coach who stuck. They've all fumbled on the field and stumbled on the sidelines, with several embroiled in headline-grabbing scandals — including McCartney.

But with Deion Sanders, CU thinks it finally has a winner. And McCartney himself agrees. “I like this guy. Neon Deion. He’s the real deal. I can’t wait,” McCartney told the Denver Post’s Mark Kiszla.

Here's a look at the head-coach roster over the past four decades:

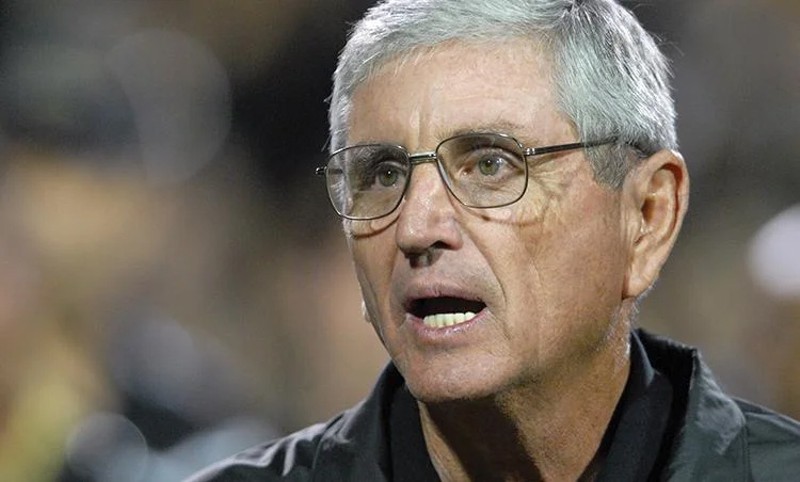

Bill McCartney 1982-1994

Bill McCartney got off to a slow start but eventually picked up the pace. He strategically recruited inner-city Black athletes who scored on the field but had trouble in the largely lily-white city of Boulder.

According to a 1989 Sports Illustrated story, eighteen athletes on the 1987 roster alone were arrested and 65 were contacted by police. Their alleged, and often substantiated, crimes included trespassing, sexual assault, drunk driving and more. “Critics of the Colorado program suggest that McCartney has lost control of his athletes. But some observers say that Boulder gives the Buffs a difficult time — especially if they are Black, as most of the arrestees have been,” the magazine wrote.

The school scheduled seminars to educate the players about date rape, and McCartney didn’t escape scrutiny. "It's obvious to me that one more spot in that date-rape seminar should be reserved for the football coach," said Alex Hunter, then Boulder’s district attorney.

McCartney was also embroiled in controversy for his evangelical Christian views, which seemed to contradict the behavior of the athletes on his team, particularly the two who had children out of wedlock with McCartney’s daughter.

In 1985, the American Civil Liberties Union threatened CU with a lawsuit charging that McCartney held inappropriate mandatory prayer sessions and gave players who agreed with him religiously extra playing time, an accusation McCartney denied.

In 1992, he got in hot water again when he was accused of passing out Bibles with the CU logo on the cover. He was vehemently anti-gay, throwing his support behind Colorado for Family Values, which pushed Amendment 2, a ban on laws protecting gay people from discrimination.

''What he is, is a university preacher with another title,'' said Christof Kheim, then Colorado's student-body president. ''He’s a bad fit at this university. I can’t help but think his comments have hurt a lot of people, and I keep wondering why he’s allowed to get away with this.”

In 2010, when McCartney's name was floated for a second stint as coach, CU employees said he should be disqualified because he had used his position to push anti-gay and sexist agendas.

Among other things, he'd founded Promise Keepers, a Christian men’s-rights group. When he abruptly left the school in 1994 with ten years left on his contract, he continued to run the now-renamed organization.

“By now, football fans and astonished bystanders also know about the bizarre flip side of McCartney's success,” Bill Gallo wrote for Westword in 1995. “About assorted lettermen who popped up in handcuffs at the Boulder police station almost as often as they did at football practice. … And the head coach's increasing devotion to fundamentalist Christianity.”

Still, McCartney is beloved by much of the Buffalo faithful, who yearn for a return to the glory days of a winning football program.

Rick Neuheisel 1995-1998

McCartney was a tough act to follow, especially because he was expected to stick around for another decade. His successor, Rick Neuheisel, earned a respectable 33-14 record during his four years as the school’s football coach before leaving for the University of Washington.

Gary Barnett 1999-2005

The university then hired Gary Barnett, a former McCartney assistant. He was not as successful on the field, totaling a 49-38 record, but his worst offenses came off it. Three women sued CU in federal court, saying they'd been raped at a 2001 party. Four of the party's attendees were football players, and two were recruits.

By 2004, eight women had accused CU football players of rape. Barnett was placed on administrative leave that year, in response to comments he made about former Colorado football placekicker Katie Hnida’s charge that a teammate raped her in 2000. Separately, the state was investigating alleged recruiting improprieties at the school, including the use of drugs, alcohol and sex to entice football athletes to commit to the program.

“The recruiting, rape and party scandal that has shaken the University of Colorado football program to its foundation has yielded one incontrovertible fact: Whether he was an enabler or not, whether he endorsed the late-night frolicking or he didn't, head football coach Gary Barnett made little effort to grasp what was going on or not going on with his players,” Westword wrote.

In 2005, Barnett was finally let go after a poor season on the field, accepting a $3 million settlement.

Dan Hawkins 2006-2010

Things didn’t improve much under Dan Hawkins, who led the team to an unfortunate 19-39 record over four seasons. It wasn’t just on the field that Hawkins had problems: CU lost five football scholarships after the NCAA found the school fell short of Academic Progress Rate standards between the 2009 and 2010 seasons.

Hawkins was fired a year before his five-year contract was up, leaving with a $2 million buyout.

Jon Embree 2011-2012

Next came Jon Embree, the school’s first Black head coach. Embree was a disappointment on the field, coaching the team to a 4-21 record during his two seasons. Still, McCartney argued that Embree should have been given more time to build the program before being let go, saying he suspected a white head coach would have been given much more leeway (see: Hawkins).

When Embree and offensive coordinator Eric Bieniemy were both kicked, the school paid them nearly $2.5 million combined.

Mike MacIntyre 2013-2018

Mike MacIntyre brought a slightly better athletic performance to Folsom Field, though a 30-44 career record isn’t much to brag about. Still, MacIntrye managed to win Coach of the Year in 2016. But as with Hawkins, his mishandling of sexual assaults within the program led to his eventual firing.

Pamela Fine told MacIntyre in 2016 that she had been abused by CU assistant coach Joe Tumpkin; MacIntyre didn’t act until the media got involved. Tumpkin was suspended in January 2017, and he resigned after being charged with five counts of second-degree assault and three counts of third-degree assault.

Despite that, MacIntyre signed a five-year contract extension in 2017. He'd been paid an annual salary of $2 million; the extension gave him an additional $800,000 more each year, with annual increases. The school also snuck in a $100,000 bonus to be paid at the end of the contract — which equaled the amount MacIntyre was ordered to donate to a domestic-violence fund after former U.S. senator Ken Salazar determined he had erred in his handling of the Tumpkin situation.

By the time he was fired a year later, the school had set itself up to owe MacIntyre $10.3 million. He left with a payout of just over $7.2 million.

Mel Tucker 2019

Mel Tucker is still a sore spot for many CU fans; he spent just one year at the university, during which he tallied a 5-7 record. Just days before he ditched the Buffs to head to Michigan State University, Tucker tweeted that he was still committed to Colorado football. Not so much.

One bonus: For the first time since 1988, the school didn’t have to fork over any cash to a departing head football coach. Instead, Michigan State bought out Tucker's contract and covered a $2.5 million tax liability.

Karl Dorrell 2020-2022

During Karl Dorrell’s short stint, he earned a sorry 8-15 record. When CU fired Dorrell partway through the 2022 football season, the team hadn't won a single game. Even so, CU owed him a total of $8.7 million.

Gerad Christian-Lichtenhan is one of the few athletes on the team today who dates to the Mel Tucker days. He's tried to stay grounded through each iteration of the coaching carousel. “There's obviously going to be some doubt, some trust issues there,” he says. “But I took it in stride, and I wanted to make sure that no matter what happened, I learned something from each coach.”

He’s looking forward to what he hopes will be an era of stability under Deion Sanders.

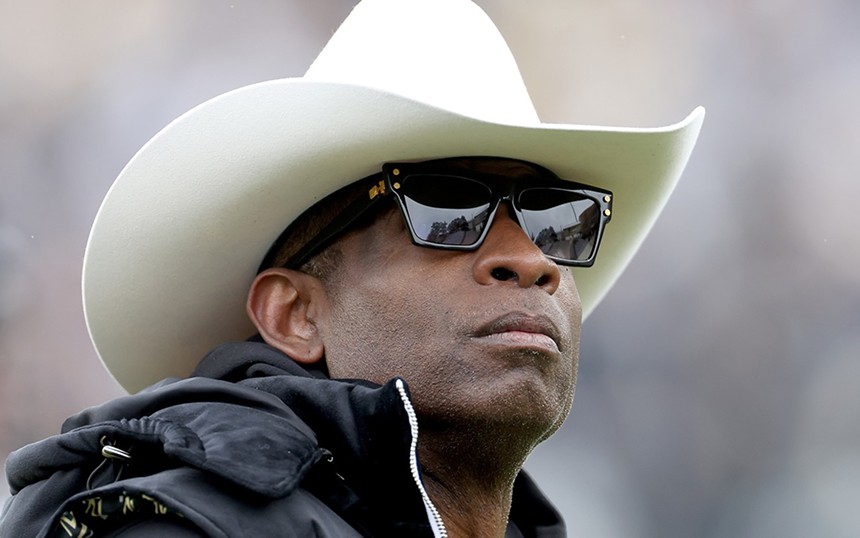

Deion Sanders

Before Sanders was hired, Denver Gazette columnist Woody Paige took CU Athletic Director Rick George to task over the sorry state of the school’s football program. “If this place is to become a powerhouse or Folsom Field a respectable home again, the next McCartney must be found,” Paige wrote. “Good hunting, Rick.”

Sanders has a bit of the McCartney spirit, not shying away from controversial statements — such as those he made in February on The Rich Eisen Show about the type of family he wants certain positions to come from.

“We want mother, father, you know, dual parents,” Sanders said, referring to quarterbacks and offensive linemen (who fare best with a “strong father,” he added). With defensive linemen, Sanders looks for “single mamas.”

Still, CU athletes are excited to play for Sanders, and if he departs CU early, as he did with Jackson State, where he'd coached for the past three years, he’ll likely leave disappointed fans and players in his wake.

And he'd owe the school. If Sanders leaves by his own choice before the end of 2023, he will owe CU $15 million. The amount decreases each subsequent year, with Sanders owing $10 million if he leaves before 2024, $8 million if he leaves before 2025, $5 million if he leaves before 2026, and $2 million if he leaves before 2027.

If he is fired for a reason not specified in the contract (those spelled out mostly pertain to breaking NCAA, school or legal rules), then CU will owe Sanders 75 percent of his remaining salary.

But the school isn’t thinking about that now. Because Sanders is so different from any previous head coach, CU expects a positive future.

“In terms of what sets Coach Prime apart, he is an icon with a Hall of Fame pedigree who is recognizable throughout the country,” the school says in a statement. “He’s not just unique to coaches in Colorado history, but arguably college football history. It’s exciting to have a person of Coach Prime’s stature join the line of legendary University of Colorado football coaches.”

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "leaderboardInlineContent",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "tower",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

}

]