And now all he wants to do is own a food truck here — but obtaining a business license is no easy accomplishment for someone whose status as a legal resident is constantly challenged. That's why Flores-Muñoz has been working with the City of Denver to clarify licensing requirements and remove some bureaucratic red tape.

Flores-Muñoz is one of approximately 17,000 Colorado residents covered by the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program implemented by the federal government in 2012. DACA rules stipulate that those covered must file for renewal every two years or face the possibility of deportation. Now 29, Flores-Muñoz considers Colorado his home, even though he must entreat the government to let him stay here as frequently as most of us get our vehicle emissions tested.

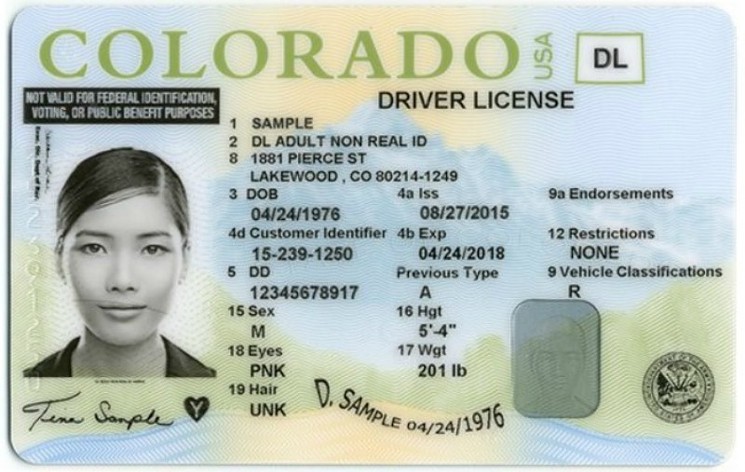

"I am right now lawfully present in the U.S.," Flores-Muñoz explains. But because of his DACA status, his driver's license includes a black bar containing the words "Not valid for federal identification, voting, or public benefit purposes."

Last fall, Flores-Muñoz and his business partner purchased the Stokes Poké food truck, a seafood spot on wheels whose business license is currently in the partner's name. Flores-Muñoz was told that he couldn't use his driver's license as identification to get a business license through Denver's Department of Excise and Licenses because a business license is considered a public benefit, according to a federal regulation (8 U.S. Code § 1621). And under a Colorado law that passed the legislature in 2006, HB06-1023, local agencies must "verify the lawful presence in the United States of each person 18 years of age or older who applies for public benefits, as defined in federal law.”

As a result, applicants with DACA status end up falling into a rabbit hole of cross-referenced regulations, documents and checklists, none of which directly states whether an "undocumented immigrant with deferred action," such as Flores-Muñoz, can actually get a business license in Denver.

A sample of a driver's license with the black bar reading "Not valid for federal identification, voting or public benefit purposes."

Colorado Department of Motor Vehicles

But according to Flores-Muñoz, getting a business license is just one of the hurdles that undocumented immigrants face when trying to build a venture in Denver. A political activist who recently quit a full-time job at America Votes to pursue his "side hustles," he says that one of his goals is to help other people in his position earn money through legal entrepreneurship. "Often immigrants don't have any other choice but to start their own business — cleaning houses, catering, selling goods to their neighbors," he explains. "I work within the system, I work with elected officials. But I worry for people who are not like me, who don't know the system or don't speak the language."

Jamie Torres, director of the Denver Office of Immigrant and Refugee Affairs, recalls that Flores-Muñoz came to her last year to ask why he couldn't get a business license. "If individuals feel like they won't be able to use their drivers' license because of the black bar, then they feel like they have no other options," she says.

With the new clarification from the Department of Excise and Licenses, it will be easier for applicants to understand what they need to provide, she adds.

Still, some DACA recipients may not think that obtaining a business license is even a possibility. Torres says that's why the city is holding a public event at noon Tuesday, April 2, at the Wellington Webb Municipal Building, where Flores-Muñoz will be the "first" DACA recipient to be handed a business license. (The department has already been set up to accept other applications.)

With license in hand, Flores-Muñoz will fulfill another step on the road to becoming a true Colorado businessman. He points out that he purchased the food truck, which occupies a slot at food-truck collective Finn's Manor in RiNo, without a loan, since getting financing is another obstacle for undocumented immigrants. Instead, he saved his money until he could make it happen.

Flores-Muñoz says he's been telling other DACA recipients that getting licenses is easier than it used to be, but he also points out that other undocumented immigrants not covered by DACA have fewer options. So he'd like to see the requirement for the affidavit of lawful presence removed and HB06-1023 repealed.

Even then, these immigrant entrepreneurs will face a lifetime of uncertainty. "There is no way for me to apply for a green card or citizenship," Flores-Muñoz explains. "There is no line available for unauthorized immigrants, and the 'regular channels' are not accessible to us."

Flores-Muñoz will soon be able to display his Denver business license; he'll be able to sell seafood as the co-owner of Stokes Poké. But he may never be able to call himself a citizen, or even a permanent resident, of the only country he's known since childhood, the country he calls home.