Kevin Morrison, owner of Tacos Tequila Whiskey, had just debuted his Pinche Tacos food truck earlier that summer. "A girl came up to the truck and ordered one taco, and I asked how long she'd waited, and she told me an hour and a half," he recalls. "So I ended up just giving her one each of all of our tacos."

The event was the inaugural gathering of the Justice League of Street Food, a semi-regular food truck rally that popped up in various locations for three years before running out of gas. And in recent years, food trucks — which glamorized the mobile concept initially embodied by loncheras serving local work sites and a blue-collar clientele — have rarely elicited the kind of mad frenzy of that summer.

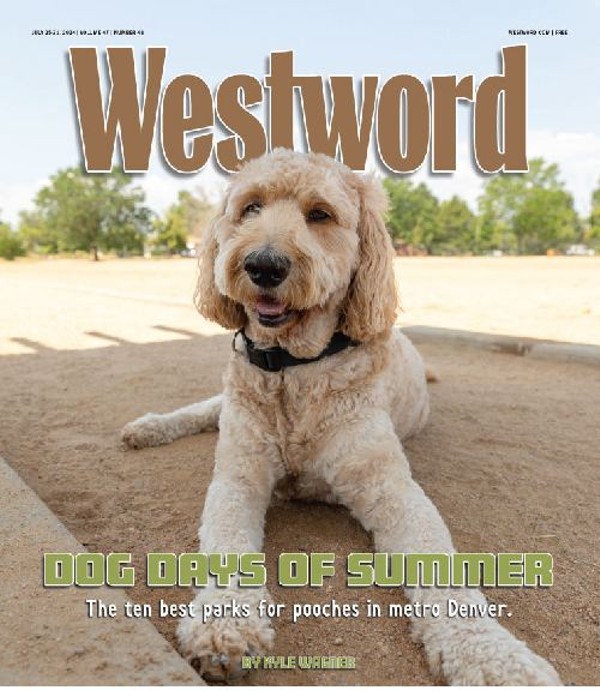

Civic Center Eats has grown from a handful of trucks to the city's biggest mobile food rally, but hasn't been able to open so far this year.

Danielle Lirette

Pinche Tacos was one of the first trucks at Civic Center Eats, and remembering those times really revs Morrison up as he thinks about both the opportunities and the irreverent attitude that got him in trouble with the city.

In the early 2000s, Morrison had founded the Spicy Pickle sandwich shop in Capitol Hill, which expanded to several locations and then went corporate a few years later. The board of directors had no need for the company's founder, though, so in 2009 he found himself out of a job but with shares in his old company. He sold some to buy a truck for his new Pinche Tacos venture. "It was great timing — not that I planned it that way," he admits.

That summer, Morrison had applied to peddle tacos from a cart on the 16th Street Mall, but his application was denied by the Downtown Denver Business Improvement District on the grounds that "pinche" is an obscenity in Spanish. He changed the name on one cart to Tacos Borrachos and got the okay for downtown sales; he used that same name when his truck served its first tacos at Civic Center Park the next summer. But after those early mobile successes, he focused on opening the first in what would become a small string of brick-and-mortar taquerias, settling on the name Tacos Tequila Whiskey to mollify the bureaucrats.

It's been a long time since any of his carts or his truck have operated in Denver, Morrison says. The truck made its way to Phoenix for a brief spell when Tacos Tequila Whiskey had an outpost there from 2017 to 2019, but now it's returning to Colorado. "We didn't run it for about three years because it was so hard to manage staffing it," he explains. "But we liked to use it as a training tool for management, because it represents where we came from and where our roots are."

This summer, though, Morrison is getting back to his roots...and he's not the only truck owner to do so, since mobile eateries are uniquely suited to serving customers during the coronavirus pandemic. Morrison will relaunch his taco truck at the Stapleton Farmers' Market, and he also has some private events booked. "I found the old shirt and hat that I wore that first summer, and I'm going to wear them again," he says. "They're a little beat up, but they're a great reminder of the early days."

The Pinche Tacos fleet eventually lead to the opening of Tacos Tequila Whiskey.

Courtesy of Tacos Tequila Whiskey

After dominating downtown streets and events for several years, Biker Jim's Gourmet Dogs opened a fast-casual eatery in the Ballpark neighborhood in 2011. Drew and Ashleigh Shader, the owners of Atomic Cowboy, hit the streets with the Biscuit Bus in 2009 before expanding to four Denver Biscuit Co. locations in Denver and Aurora. The Steamin' Demon was the mobile offshoot of City, O' City, which remains a vegetarian mainstay in Capitol Hill. And while the Denver Cupcake Truck was retired, its owner, Cake Crumbs Bakery & Cafe, still makes great baked goods.

Perhaps the most iconic Justice League truck during the summer of 2010 was Pearl, the four-wheeled representative of Steuben's Food Service, which restaurateur Josh Wolkon had opened four years earlier. Pearl wasn't the first gourmet food truck in Denver, nor was it the most innovative, but its bright-blue wrapper with the retro striping and logo quickly came to signify great green chile cheeseburgers, shoestring fries and even the occasional lobster roll to diners around the city.

"Pearl, our original truck, was a baby step," Wolkon explains. "We wanted to do something like Shake Shack at Civic Center Park, but realized that wouldn't work."

Instead, Wolkon purchased a somewhat run-down truck from a taco vendor on Federal Boulevard and had it completely refurbished, converting the engine to biodiesel and adding solar panels on the roof. "It burned its own fryer oil, but it only worked about 60 percent of the time," says the restaurateur, whose brick-and-mortar offerings started with Vesta more than two decades ago and continued with a second Steuben's in Arvada and Ace Eat Serve. "It always smelled like French fries when it was running, and since then, we've replaced every single mechanical part of that truck."

Wolkon just sold Pearl, but he still operates Gunther, another used truck he purchased and retrofitted. "We've done a ton of nonprofit events, auctions for charities, Film on the Rocks and other big events," he notes. But COVID-19 has changed Gunther's mission. "We're trying to serve at places that have lost their cafeterias," Wolkon says. "Manufacturing and distribution centers — the kinds of businesses that need to feed their employees but can't do it the way they used to be able to."

Recently, Steuben's has been using the truck to feed workers at the Nestle Purina plant off Interstate 70, providing contact- and payment-free meals during three shifts. Later this summer, when it's clear that small social gatherings are safer, Wolkon will roll out the Ace Bar Bus for private bookings; he sees the service as a way to help customers enjoy the summer while sticking to their own back yards and neighborhoods for comfort. "We can show up at your house and serve you just about anything," he promises.

"Those days of the Justice League, we felt like we were on the frontier of something new," Wolkon reminisces. "The red tape wasn't there, the restrictions weren't there. We could just show up and do what we love doing."

To keep doing that, Wolkon just purchased his first brand-new food truck, which he's already christened Stu. It will have the same blue wrap and now-iconic Steuben's logo, as a signal to customers that they're getting the best from an established name.

All over the city, food trucks are changing course to better deal with the new realities: Craft breweries are closed for all but to-go service; festivals and concerts have been canceled; catering gigs have dried up. Some vendors have found new directions altogether: Jason Bray and Amy Crowfoot, owners of the J Street and Hunje food trucks, are now handling culinary operations for the just-opened Spice Trade Brewery & Kitchen and have put their mobile business on hold. The Adobo food truck, which serves Filipino and New Mexican cuisine from owner Blaine Baggao, has been posting photos on Instagram showing its preparations for taking over the kitchen at the Monkey Barrel in Sunnyside; Adobo's first menu for the new location went live on May 20. Another Filipino vendor, the almost-decade-old Orange Crunch, has been posting up regularly at the Old Man Bar in Broomfield since the bar was closed to on-site service; it will soon move to a new location, since the Old Man is reopening its own kitchen.

One of the few newer trucks to achieve the popularity of Justice League days is Penelope Wong's Yuan Wonton, which launched last summer and soon inspired a devoted following, generally selling out within a couple of hours. During the pandemic, Wong tried switching to online pre-orders to maintain contactless service for the safety of her customers and crew, but the demand for her dumplings was so high that the system was more frustrating than rewarding. So she switched to serving meals to front-line health-care workers, and has only recently begun serving customers again. "In adapting our business model and our service platform, the priority will be to maintain an environment in which your (and our) safety is first and foremost," Wong recently wrote on Instagram. "Our only option to get back out there right now is to concede to online ordering in all its glitchy glory....Please be patient with us."

For now, the days of bodies pressed close together in long lines, of park benches and picnic tables overflowing with street food and hungry diners, will remain just memories. But the trucks will keep rolling. You may find yourself sitting in your car, placing your food-truck order on your phone and having your meal brought out to you drive-in style. Or you might run across a food truck with a short line of customers spaced six feet apart while you're picking up growlers or cans of beer from your neighborhood brewery. There will be no hour-and-a-half wait for a single taco, no sharing of bites of global cuisine that you and your friends have collected from multiple trucks. And Civic Center Eats missed its planned launch date this spring and remains on hold until further notice; in the meantime, it's promoting its roster of food trucks on social media and even hosting an online ordering site at civiccentereats.com.

But when things do return to some form of normal, don't let another decade pass during which you take Denver's street vendors for granted, thinking they'll always be around dishing up empanadas, lumpia, soup dumplings, slow-smoked meats or other dishes from far-flung corners of the culinary world. The chefs handing you a paper boat loaded with their best efforts have been there for us all along — so we should be there for them this summer.