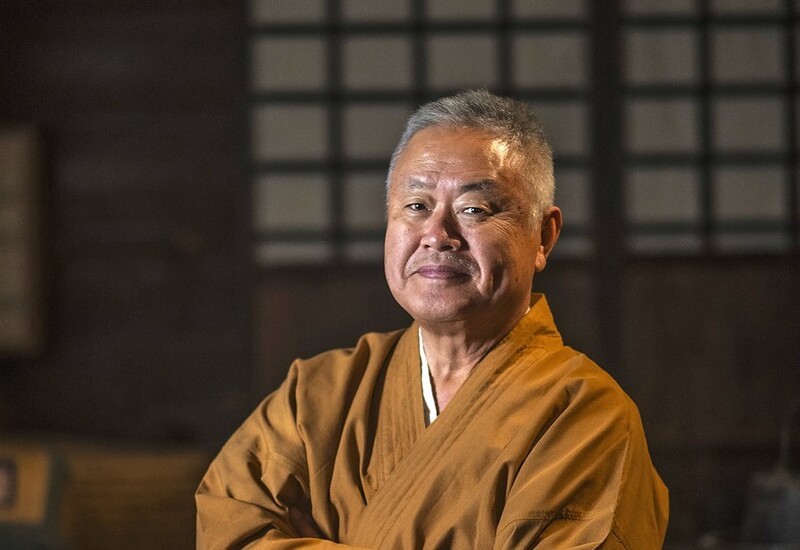

Gaku Homma, the owner of Domo Japanese Country Restaurant, is working the grill in a crowded kitchen about the size of a food truck, where three chefs are cooking while several other employees drop off orders and pick up dishes for customers out in the dining room.

Homma makes it look easy, searing thin-sliced meat on the teppanyaki grill, then adding various vegetables as he separately scorches squares of flattened rice for Okoge Butanabe, a new dish that his downsized menu notes is “from DOMO Executive Chef’s Hometown.”

The grilled proteins and veggies are simple; what makes the dish unique is the burned and crisped rice. Since the introduction of the electric rice cooker (invented in 1950 and popular by the 1980s in Japan), it’s become less and less common to have kogeru gohan, or burned rice, a common outcome of rice cooked in iron pots over flames. So he’s re-created the experience with this new dish.

He calls out commands to the staff as they spin and pivot around him. “Hai, Gatsuri Beefu!” he says as he drizzles sauce on a bowl of thin-sliced beef over rice, complimenting one of his sous chefs, who immediately steps in and cleans the teppanyaki grill as Homma steps away to start his next dish. He's been working with this sous for nine years, and the operation looks amazingly smooth and choreographed despite the inherent chaos.

Outside the busy kitchen, the spacious dining room is peaceful, with about fifty diners. No customers are waiting to be seated; there are no lines outside.

It wasn't always this way. In recent years, Domo was struck by a double blow that almost ended the 26-year-old restaurant.

Like many small businesses, Domo had already been hit hard by coronavirus shutdowns when a TikTok video showing Domo and its unique country decor and Japanese garden went viral in the summer of 2021. The next morning, hundreds of curious diners were already in line when Homma opened the restaurant.

Soon, people were waiting for up to two hours in lines that stretched from 1365 Osage Street to West Colfax Avenue. With a shortage of staff, Domo wasn't equipped to deal with the explosion of business. Homma scrambled to explain what had happened on the restaurant’s Facebook page and posted signs apologizing for the long waits. He called the police when frustrated would-be customers got in fights or became unruly.

Finally, Homma closed Domo temporarily in January 2022; when the restaurant reopened, it was with capacity restrictions and shorter hours. But the workload was still too much, and he worried about the quality of both the food and the service.

"Tsukareta," the 72-year-old told Westword. "I'm tired."

In September 2022, he closed the restaurant — for good, he thought. As Homma recalls his formative years and discusses decades of work at Domo, he uses the word "binbo" — pronounced “beenbo” — several times. The word means “poor,” and that’s how he describes his childhood.

His father was a high-ranking officer in the Japanese Army in Manchuria during World War II, so he wasn't exactly enthusiastically welcomed back to Japan during the U.S. occupation of the country in the years after the war. He supported his family, including son Gaku, who was born in 1950, by working hard at menial jobs and making do in Akita Prefecture in northwest Japan (yes, where the famous curly-tailed dogs are from).

That work ethic led Homma to embrace the martial art of judo, and then aikido, at a young age. When he was fourteen, he was sent by his father to study aikido with the founder of the discipline, Morihei Ueshiba, at his dojo in Tokyo, and then Ueshiba’s compound in Iwama, a small town north of Tokyo.

Homma describes his life before he was accepted as an uchideshi, or live-in student, as mostly that of a servant: cleaning, attending to the master and the senior students, and cooking meals for them.

When he became an aikido sensei, or teacher, himself in the 1970s, Homma began instructing members of the U.S. military stationed at Misawa Air Base in northern Japan. As his students rotated out of the service, he was invited by some to visit the United States.

Homma arrived in San Francisco at the tail end of the anti-war hippie era and was talked into buying a beat-up van for a cross-country drive. In a flip of the common story about young people heading from the East Coast to California whose cars broke down in Colorado, Homma’s van broke down here as he headed east. He decided to stay.

Homma launched Nippon Kan, his aikido dojo, in 1978; he originally shared space with a judo dojo before opening his own place on East Colfax Avenue. Inspired by his own days as an uchideshi cooking meals for Morihei Ueshiba and his charges in Japan, he started offering dinner to some of his Denver students after class. When the dojo was damaged by a fire, he moved into what was then a relatively run-down part of town, in an old warehouse space just blocks from the then-new Auraria campus. He created a studio for training, as well as space to house uchideshi.

Soon he added a cramped kitchen and dining room for a restaurant that could support Nippon Kan and help pay for the international students' training. ”Dojo tabe ni — the restaurant opened,” Homma says, explaining that "for the sake of the aikido dojo," he opened Domo.

From the start, it was important to Homma that a meal at Domo not be a typical restaurant experience.

The property, which backs up to railroad tracks, was already fenced in and included an outdoor area with a Japanese garden complete with koi pond; he put seating there. The building attached to the dojo had more seating, and he added a Japanese farmhouse museum with artifacts, implements and a replica living and cooking space around a charcoal burner on the mat floor.

“When I was working on the interior of the restaurant before the opening 26 years ago, many people asked me why I was spending so much time and effort [on elaborate designs and embellishments], as they thought having a few Japanese posters on different walls would suffice,” Homma recalls. “I had a vision and forged ahead with the vision because I wanted the place to be somewhere for people to feel as though immersing themselves in Japan, even for sipping just a cup of water. It makes me feel pleasant, honored and humbled to know that many people have made their fond memories at this place.”

The unusual tables — stone slabs pulled up from the flagstone sidewalks alongside Osage Street and balanced on thick tree trunks — took a lot of labor to create, but they reflected Homma's “binbo” mentality, since the materials were free. The trunks supporting the tables, as well as those covered with padding that serve as seats, were all recovered from Colorado wildfires or pulled out of Cherry Creek. So were the gnarly wood pieces wrapped with Japanese newspapers that serve as funky chandeliers.

All of the artifacts that adorn the dining room and museum were collected by Homma during trips to Japan or donated to the dojo. When he traveled with delegations of students, he made them bring back the artifacts in their carry-ons.

For years, Homma displayed hundreds of shallow ceremonial sake cups in glass cases in the museum, but they were not from Japan. He collected them from garage sales and antique shops here in the U.S. These were wartime souvenirs left behind by teenage boys who were conscripted at the end of WWII to fly suicide missions as kamikaze pilots; they were given a final toast of sake before they took off on their final flights, and the cups were brought back by American GIs after the war. During the pandemic, Homma donated them to the Heritage Museum in Higashinaruse Village in Akita, with which Nippon Kan has an exchange relationship.

“Although I had received multiple high-value offers from collectors in the U.S. because such an extensive collection of military sake cups that I had accumulated was so rare and so valuable even in Japan, I decided in the end that having them come home — i.e., 'satogaeri' [homecoming] — would be the best choice,” he says.

That was not Homma's first generous act. From the start, drawing from his early aikido training to do good for the community, he envisioned charity work and volunteering as a hallmark of Nippon Kan. In 1991, he formalized that with the creation of the Aikido Humanitarian Active Network. Since then, he estimates, he's provided over 100,000 free servings of Japanese curry for AHAN's Monthly Meals Project, where aikido students help prepare meals for the needy. He posted photos on the restaurant's Facebook page just before Christmas to mark the last Monthly Meal of 2023.

After he closed Domo in late September 2022, Homma took off on world travels, visiting countries where he operates orphanages, schools and aikido dojos — including Brazil, Mongolia, Nepal, Vietnam, Thailand and the Philippines. He stopped in Tako Lang province in Thailand, where he helped fund and build Bilay House, a home for refugee children who escape the violence and political turmoil of Burma. While there, he served his trademark Japanese curry for Bilay House residents. He posts messages and photos from his young charges on Domo's Facebook page, too.

He got married in Thailand; his wife will move to Denver this year and into the Domo complex, where Homma has lived for more than three decades.

Through most of the ups and downs of the pandemic, aikido classes continued at Nippon Kan. They aren’t as big as they used to be, but Homma is proud that they’re still held on the premises. He's also continued to instruct members of the military; he recently trained Nepalese soldiers in aikido and hosted members of Nepal's army at his dojo.

And now Domo is back in business, too.

The hours are more limited and the menu is smaller; for the time being, Homma has cut out some of the items he'd added over the years, things like the Wanko Sushi and his ramen bowls. They'd been reluctant nods to the growing popularity of certain Japanese foods; with not-so-great sushi available at supermarket chains and ramen sold by any number of inauthentic hipster eateries, he thought he needed to keep educating his audiences about real Japanese cuisine.

He'd always been creative with his “country cooking” because he grew up “binbo,” so you won’t find pricey wagyu beef, high-toned handroll sushi or $20 bowls of ramen at Domo. Homma currently serves only udon noodles because they’re popular in his soy-based broth and with curry, his most popular dish (along with curry served over rice). His food palate is not fancy. It’s comfort food.

While he might add more menu items and bring back other dishes, for now the menus will remain the same through lunch and dinner. Like his news about charity and volunteer work, Homma posts menu updates on the restaurant’s Facebook page, which are translated from Japanese by one of his staff.

Of the dinner hours added this month, he explained: “I’ve arrived at this decision not only as enough number of staff has been secured with newer staff having been trained adequately, but also because we could not offer the quality of service we wanted to offer when we had to serve so many customers in short hours of lunch time and because we have received such requests from customers."

The clamor of customers was key to his return, Homma says. And you can tell he loves what he does. Every chance he gets, he walks the floor of the dining room and stops by the tables to speak with patrons.

One recent afternoon, he encountered two couples whose first dates were at Domo — albeit decades apart. One has been coming to the restaurant for many years; the other, a young couple, was celebrating a recent engagement. “I was pleasantly surprised, but I also felt very fortunate to meet with two couples who had heart-warming, life-changing events at Domo," says Homma.

Laura Bergroth, a third-generation resident of Denver, was having lunch with her husband, Warrick, who’s originally from Australia but has lived in Denver for thirty years. “So we had our first date here at Domo, and I had known about it for a long time. And the fact that he knew about it and picked the restaurant meant that I had to give him a second date," she says. “It's such a special unique culinary and cultural adventure. The spicy tuna donburi — I was so happy to see that added to the menu."

Nathan Brooks and Eun Seoul had their first date at Domo four years ago. “Then yeah, there was that pandemic thing," Brooks says. "So we recently found out that it was open again, and it’s really cool to be back here.” Especially since they just got engaged.

Other regulars were also on hand. Shane Campbell has been a regular since a friend introduced him to the restaurant in 2000. He and another friend, George Lemonis, were back for lunch, and both ordered curry udon.

“I can’t say it’s my favorite, because I haven’t had a bad meal yet at Domo,” Campbell says. “I’ve had every dish here, and I love every dish here. I found out about it closing on my newsfeed on my phone, and I was like, ‘Oh, no, no, please don’t.’ I wasn’t happy about it, let’s put it that way.”

Lemonis is a relative newcomer to Domo, but says he would like to take beginner aikido classes at Nippon Kan.

Homma would welcome him as a student. After all, it would be a natural progression for a diner at Domo to become a student at his dojo. Even his employees call him "sensei," or teacher, and Homma is always quick to say that his main job is to run his Nippon Kan. But his second job is gaining in importance: his work through AHAN, where he supports charitable efforts not just here in Denver, but in third-world countries where there are populations in need and people going hungry. And then comes the restaurant, so beloved by local diners.

But all three parts of his life are interconnected. As his chopstick wrappers suggest: “Dine at Domo and Feed the World.”

Domo Japanese Country Restaurant is located at 1365 Osage Street and currently open from 11 a.m. to 8 p.m. daily (except Sundays). Find out more here.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "rectangle",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet|mobile"

}

]

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25,

"watchElement": ".fdn-content-body",

"astAdList": [

{

"adType": "leaderboardInlineContent",

"displayTargets": "desktop|tablet"

},{

"adType": "tower",

"displayTargets": "mobile"

}

]

}

]