By the time the windstorm was over, displaced earth had drifted over much of McCauley’s front porch and his spring lambing pasture, and piled a foot deep along the fence at the edge of his farm.

McCauley was all too aware of the fragility of the neighboring property, which has been owned by the City of Boulder Open Space since 2007. He practices regenerative farming — growing food while also caring for the land in a sustainable manner — on his own place, and for the past three years has also worked to revitalize the soil next door, which had been rendered unusable by years of continuous overgrazing and a dense prairie dog population.

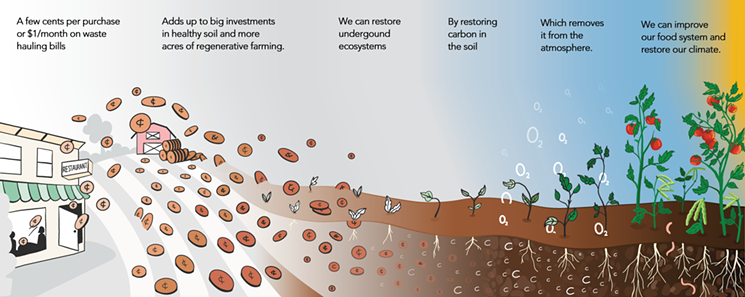

McCauley is part of a growing movement of farmers, ranchers, organizers, government agencies, restaurateurs and everyday people trying to support a cultural revolution in farming, one that values soil as the linchpin for supporting life. This approach prioritizes healthy soil as the foundation of a resilient ecosystem. At the local level, the soil nurtures plant, animal and human life; at a global level, it stores excess carbon, helping the world combat CO2 buildup in the atmosphere — a major contributor to climate change.

In Boulder County, proponents of regenerative farming have joined together to support a pilot program called Restore Colorado, which directs crowdfunded grant money to the places and people where it can make the most difference. At the heart of this new public-private collaboration is the belief that the food system has enormous potential to reduce greenhouse gases and help the planet.

In the process, McCauley believes, it can heal the land.

Marcus McCauley looks at the land on the neighboring property after the windstorm stripped the soil.

Phil Taylor

Much of the land was bare, plowed up for a building project that never materialized. To reclaim it and enrich the ecosystem — by building back nutrients and microorganisms that help retain carbon in the soil — McCauley has employed compost applications, cover cropping and keyline plowing, a technique that helps soil absorb rain. Unlike conventional agriculture, which has traditionally relied on farming large swaths of land with soil health often an afterthought, regenerative agriculture seeks to disturb the soil as little as possible.

It “points to a way of farming, depending on people’s focus, and it’s called many things,” McCauley says. “It’s like sustainable agriculture 2.0.”

One of the first recipients of a Restore Colorado grant, roughly $18,000, McCauley plans to use a portion of the funds to add compost to his pasture fields. Composting helps jump-start life in the soil by re-infusing it with nutrients. It also reinforces the fertilization cycle that occurs naturally when ruminant animals cohabit with grass.

McCauley mimics this natural process by practicing rotational grazing, another regenerative technique. He methodically shifts his sheep from pasture to pasture so that they can eat and move on, then brings in pigs and chickens to further aerate and fertilize the soil. Gentle grazing helps the grass grow, because the animals loosen the soil and fertilize as they go along.

Undergrazing can be just as dangerous as overgrazing, because the grass won’t grow, McCauley explains. Centuries ago, large herds of buffalo roamed the Great Plains, grazing in different areas for short periods of time. They helped create biodiversity by eating down the grass enough for other plants to co-exist, but not so much that the grass couldn’t bounce back. Farming this same way encourages that symbiotic relationship. “It’s not the cow, it’s the how,” he says.

The McCauley Family farm has been practicing regenerative farming since 2012.

Courtesy of Marcus McCauley

He says that what’s happening there is similar to what occurred during the Dust Bowl, when a combination of over-plowing and drought led to severe dust storms throughout the Great Plains during the 1930s. McCauley’s grandmother and grandfather lived through the Dust Bowl in a little dugout home in southern Oklahoma, and his father later worked on the Oklahoma Conservation Commission. So McCauley, who grew up in Ardmore, Oklahoma, was raised thinking about the consequences of soil decline. “I was surprised to see some of the issues in Colorado when I got here,” he says, “but it makes sense.”

The combination of air pressure systems and the Rocky Mountains can create damaging windstorms in the foothills, especially in the winter. No matter the work put into the soil, wind will always be a risk. Because of this dynamic, McCauley plans to use the rest of the Restore Colorado grant to plant a shelterbelt that will also act as a food forest with grasses, shrubs and trees. So far, he’s tested cherry, apple, plum and pear trees as well as Siberian pea-shrubs and Kernza, a perennial wheat, with varying degrees of success. He also wants to include juniper, which grows naturally in Colorado’s foothills.

In addition to protecting the land from windstorms, the trees will give shade, help sequester carbon, and provide McCauley with a crop to sell and food for people to eat. It’s all part of what he sees as a functioning ecology that’s somewhere between a pristine natural state and a resource that helps sustain human populations. It’s also what McCauley calls a silvopasture: trees and pasture that reflect the natural savanna habitat of the foothills.

“I love nature, and I love the study of life, and I love the study of systems,” he says. “Constitutionally, a functioning system is a beautiful thing; I’ve come to know that. We’re building an ecology that’s appropriate to this place, but we’re also trying to feed people.”

Advocates of regenerative farming see the movement enabling long-term food security and helping to feed a growing population while also combating climate change.

McCauley met another advocate, Phil Taylor, at a farm dinner a couple of years ago. At the time, Taylor, executive director and co-founder of Mad Agriculture, was developing an alternative to chicken feed by generating his own black soldier fly larvae as a way to eliminate unsustainable components of food production.

Since it started in 2018, Boulder-based Mad Agriculture has supported projects that help farmers thrive economically and ecologically in a marriage of functionality and good practice. Among other techniques, the nonprofit encourages planting cover crops to replenish the soil and increase biodiversity, applying compost to build organic matter in the soil, introducing grazing techniques for livestock that can support grass and soil health, and using no-till planting methods that allow soils to maintain more of their nutrients. Many of these also support carbon sequestration.

Because of human activity, such as deforestation and industrialization, carbon has been building up in the atmosphere for more than 200 years. The Paris Climate Agreement, which the United States recently rejoined, seeks to sharply reduce global greenhouse gas emissions as a means to limit temperature increases.

In nature, there’s a reciprocal balance between the amount of carbon in the atmosphere, what’s being processed and what’s stored in the ground. That balance has been skewed toward carbon in the air, but this dynamic can be altered by managing soils to build up carbon, helping the atmosphere while creating organic matter that is better for plants and soil health. “You’re not only farming carbon,” says Keith Paustian, University Distinguished Professor in the Department of Soil and Crop Sciences at Colorado State University. “It improves the performance of the soil.”

Paustian has been developing methodologies for quantifying net carbon changes in the soil since the mid-1990s. Around twenty years ago, he started working with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and its National Resources Conservation Service on tools that farmers can use to assess their own impact on carbon storage.

This process — sometimes called carbon drawdown, sometimes carbon sequestration — extracts carbon from the atmosphere and stores it in the soil, reducing greenhouse gases that affect the climate.

This is where Mad Agriculture steps in. It serves as a middleman, helping farmers across the country access grant money for land-preservation projects that often also sequester carbon. In 2020, the organization worked with 26 farms; this year it hopes to double that.

However, investing in new techniques can be a huge risk when the outcome isn’t certain and the money isn’t available up front. “A farmer will grow almost anything that someone will buy,” notes Taylor. So he meets with farmers in pickups, fields and homes across the West to learn about their needs, then helps them get funding for new initiatives and find markets for their crops.

Farmers have their hands tied in more ways than one, he explains. Not only does the industry primarily support certain kinds of crops and styles of management, but farmers often have little cash on hand because their assets are tied up in their land, crops, livestock and equipment. That leaves little room to invest in new technology or approaches whose benefits, if any, will take years to see.

The agricultural industry as a whole is generally not set up to support these initiatives; conventional agriculture revolves around the need to produce vast quantities of crops as quickly and efficiently as possible. This often results in huge fields of single crops such as corn, wheat or soybeans that stretch for acres or even miles, with little plant diversity to help replenish the nutrients and microorganisms in the soil. Additional practices such as tillage — in which tractors plow the soil before planting to try to stem weed growth — further disturb the land, leaving it uncovered and at risk of erosion and carbon loss.

Regenerative farming is just one of many techniques needed to help the planet heal from climate change.

Courtesy of Marcus McCauley

That’s why Mad Agriculture focuses first on a farmer’s vision for their property. Many want a future where their land is healthy enough to support them and their family for generations to come. “Sharing meals together — that’s the beginning of all the work,” Taylor says.

During such meetings, Mad Agriculture representatives listen to the farmers’ stories and learn about their lineages, experiences and generational plans. “Whenever we work with a farmer, if you don’t have everyone around the table then, it stifles the vision or the dream,” Taylor continues. “Once we discover a shared value system, then we assess their farm ecosystems.”

Only after that do they discuss what regenerative methods can help support both the farmers and the land. From there, Mad Agriculture works to connect farmers with funds to enact their plans. There are many sources, both public and private, but Restore Colorado grants are particularly exciting for farmers, Taylor says, because they come without strings and allow them the financial freedom to determine their own path.

Mad Agriculture is a key component of Restore Colorado. Taylor’s organization provides the boots-on-the-ground function of the operation, communicating with farmers to make sure the crowdfunded money goes to the right spots.

There’s a delicate balance between what the land requires and what the farmer needs. It’s an arrangement between consumers and producers, with small improvements that make local impacts and contribute to greater global issues.

Anthony Mynit and Karen Leibowitz started Zero Foodprint in 2015 to make changing the food system more accessible.

Alanna Hale

But when their daughter was born in May of that year, Myint and Leibowitz began to think about the food system differently as they paid close attention to what they were feeding their baby. Simultaneously, Myint started researching the scientific data that suggests nutrient-rich food and sustainable farming methods have the potential to reduce some of the effects of climate change. For example, the Rodale Institute, a nonprofit dedicated to pioneering organic farming through research and outreach, believes that 100 percent of yearly CO2 emissions could be sequestered if all global croplands and pastures practiced regenerative techniques.

“It shifted the whole paradigm from anxiety and fear,” Myint recalls. “The previous mindset I had around climate was, ‘We have to do these things, but we’re delaying the inevitable.’” For him, the paradigm shifted to one of hope.

Initially, Myint and Leibowitz channeled their activism into The Perennial, a San Francisco restaurant dedicated to regenerative agriculture and sustainability in every detail. But when Myint learned that less than 2 percent of farmland in America is certified organic, he started to question the disparity between the price of organic produce and the ability of everyday people to contribute to change. He and Leibowitz realized that if change was going to happen, everyone needed to be involved.

The Zero Foodprint initiative allows restaurants and customers to chip in small amounts that contribute to large-scale change.

Kaarina McKenzie

“The ZFP community is now funding six carbon farming projects with an expected benefit of 1,245.77 metric tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2e) drawn back out of the atmosphere,” Leibowitz writes on the ZFP website. “That’s about the same as the climate benefit of 20,599 tree seedlings grown for 10 years, or not burning 140,179 gallons of gasoline.”

Zero Foodprint received the James Beard Foundation’s Humanitarian of the Year award in 2020 for its work supporting carbon farming.

There’s been a farm-to-table movement for years, but this effort is trying to create a table-to-farm movement, explains Myint. The psychological shift of words asks consumers to be aware of their purchasing power: Instead of solely seeing themselves on the receiving end of a good meal, they can also send funds back to the farms and farmers replenishing the soil that feeds them.

Restore California provided the blueprint for Restore Colorado.

Last year, Boulder was one of thirteen municipalities and counties across the country to receive a USDA grant through the agency’s Community Compost and Food Waste Reduction pilot project, designed to encourage composting and the reduction of food waste in cities and to make compost more readily accessible to farmers. Boulder officials immediately reached out to Mad Agriculture and Zero Foodprint, and together they launched Restore Colorado, a public-private initiative.

“Boulder County saw the value in partnering to bring Zero Foodprint’s circular-economy approach to Colorado to help expand Mad Agriculture’s work with farmers on improved land stewardship in Boulder County and the greater state of Colorado,” explains Tim Broderick, senior sustainability strategist at Boulder County’s Office of Climate Action, Sustainability and Resilience. “The potential for this program to be adopted and replicated across Colorado was one of the driving forces behind pursuing the grant.”

And it’s already starting to spread, according to Susan Renaud, a community engagement administrator for Denver’s Office of Climate Action, Sustainability and Resiliency. “Though Denver does not have a lot of agricultural land, we support the important work that Restore Colorado is doing to take collective action on the regional level,” she says. “This program provides an important conduit for consumers in urban areas to support the farmers.”

While Restore Colorado is still in its early stages and primarily operating in Denver and Boulder, Zero Foodprint’s focus on urban populations is designed to raise awareness and send more money to rural areas.

Consumers can do this through ZFP’s crowdfunding network, which occupies a central role in Restore Colorado.

Daniel Asher was one of the first Denver area restaurateurs to sign up for ZFP.

“I’ve always looked at food as a tremendously powerful medium for change, because we all need it to survive,” Asher explained during a recent webinar about Restore Colorado. “Restaurants are trying to figure out ways to remain viable and inspirational gathering spaces for the community. It’s a challenge.”

A self-proclaimed “eco chef” who’s both the executive chef and a partner in River and Woods, Mother Tongue and Ash’kara, Asher now gives customers at his restaurants the option of adding a 1 percent fee to their food tab. Those pennies, quarters and dollars add up to support grants that help farmers switch to renewable farming practices.

A River and Woods Market Salad is composed of locally sourced ingredients.

Courtesy of River and Woods

“Guests have responded very supportively,” he reports. “People want to help, and they want that help to be as easy and non-invasive as possible.”

Customers and staffers alike understand the simple logic of the fee, he explains: “It’s easy to just say, ‘Hey, we’re trying to take a percentage of what you’ve just enjoyed as a diner — 1 percent of the meal you just enjoyed — and we’re sending that over to a local collective that will take those funds...to create soil health and vitality.’”

In some ways, introducing it during a health crisis has helped. “The pandemic has presented us with a pretty profound awareness that we’re all inextricably linked,” Asher adds. “Within that space, there’s a lot of room to figure out how to do things better that are within our control, because the pandemic is out of our control. We can’t wake up and say, ‘Oh, COVID’s not going to affect my life today’ — but [we] can make decisions independently that affect positive change, and that is something we have control over.”

Effecting positive change is a goal for Tim Schiel, who owns five Subway franchises in Boulder. He’s planning to donate 1 percent of all profits at his stores to Restore Colorado — a slight twist on the ZFP concept. It was a hard decision to make during the pandemic, when he’s already lost hundreds of thousands of dollars in sales, but he sees the investment in regenerative agriculture as something that needs to be done. “I’m from Iowa, so I’m familiar with the farming community,” he explains.

Schiel is currently waiting on fliers and signage that will educate customers on how their contributions are helping the local community. He thinks that if his Subway franchises can do it, then other Subway stores can, too. And in that way, the movement will spread.

The goal is to make contributing to change accessible to all consumers, whether they’re able to afford an expensive meal or they frequent sandwich shops.

“We’re year one in a twenty-year program,” Myint explains.

No one will see the results of these programs and practices immediately. When you’re measuring carbon, it’s not as simple as sticking a thermometer in the soil, Paustian points out: “You have to let the change accumulate to be able to measure it.”

One of the tools that he has helped develop is COMET-Farm, which can track carbon balance in the soil over time and, based on data models, even forecast the effect of certain practices. For example, the McCauley project is expected to remove 300 tons of carbon — the equivalent of burning 33,000 gallons of gas — from the atmosphere over the next ten years.

But carbon sequestration on its own isn’t going to solve climate change, Paustian warns. If humanity is going to retain the atmospheric composition that’s supported its growth, “we have to stop putting [carbon] up there, and we have to start pulling it down. And agriculture is not going to do that alone,” he says. “There’s no single technology that’s going to do that alone.”

Still, Restore Colorado is a beginning.

It’s about more than carbon farming, more than taking care of the soil. The program is a reminder of the power of everyday people — from consumers to chefs to farmers — to help preserve the food system and the environment, from the table to the farm. It’s helping to bridge the divide between rural and urban life. “It connects consumers back to the farm,” says Taylor. “It closes the circle from farm to table. That’s really where the change is going to happen: by using the power of their consumption, human connection and relationship.”

McCauley’s relationship to regenerative agriculture is rooted in his family’s history. “I’m inspired to heal land because I come from a family of healers,” he says. “I’m inspired to do so through food and farming because of the transmission of love that came from being fed by my mother and grandmother.”

And he wants to pass that along, to the next generation and beyond. “There’s something about being responsible to them that can, I think, help folks,” he suggests. “To let go of some of the motivations that don’t serve, and move into alignment with motivations more oriented to helping everyone.”